& reviews

Art after Money, Money after Art

Creative Strategies Against Financialization

by Max Haiven

Published by Pluto Press in 2018

We imagine that art and money are old enemies, but this myth actually reproduces a violent system of global capitalism and prevents us from imagining and building alternatives.

From the chaos unleashed by the ‘imaginary’ money in financial markets to the new forms of exploitation enabled by the ‘creative economy’ to the way art has become the plaything of the world’s plutocrats, our era of financialization demands we question our romantic assumptions about art and money. By exploring the way contemporary artists engage with cash, debt and credit, Haiven identifies and assesses a range of creative strategies for mocking, sabotaging, exiting, decrypting and hacking capitalism today.

Written for artists, activists and scholars, this book makes an urgent call to unleash the power of the radical imagination by any media necessary.

Order

Sold in the UK, US and worldwide by Pluto Press

Sold in Canada by Between the Lines

Paperback ISBN: 9780745338248

Canadian ISBN: 9781771133982

Hardcover ISBN: 9780745338255

eBook ISBN: 9781786803191

A short interview about Art After Money, Money After Art

An audio version of the introduction to Art after Money, Money after Art

Endorsements

Perhaps the most theoretically creative radical thinker of the moment

David Graeber

author of 'Debt: The First 5000 Years'

Daring, brilliant, provocative. At last a radical critique of the crypto-approach and an abolitionist approach to the problem of money and art

Franco 'Bifo' Berardi

author of 'Futurability The Age of Impotence and the Horizon of Possibility'

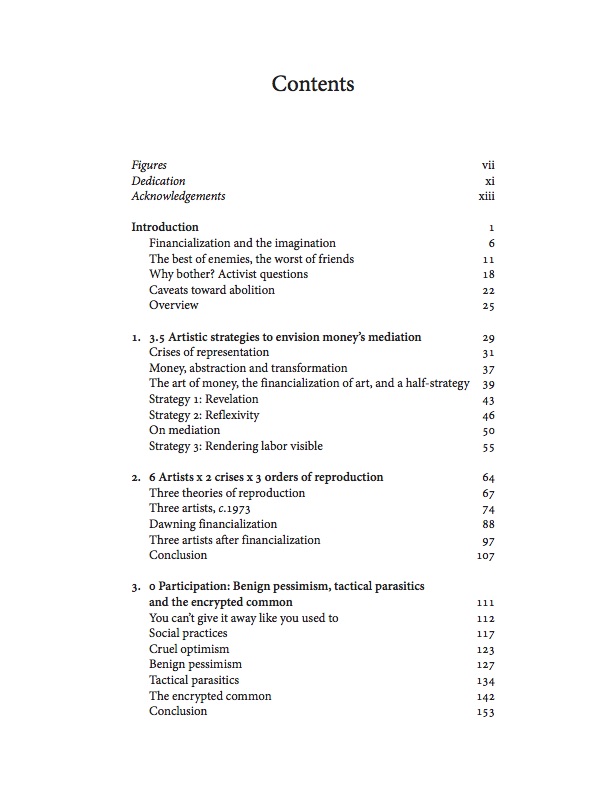

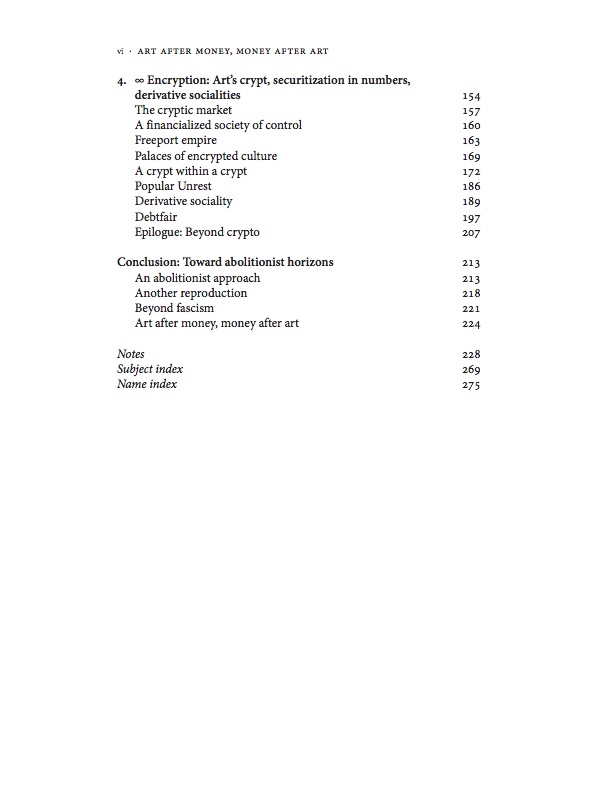

Table of contents and summaries

An overview of the major themes in the book

The first chapter, “3.5 artistic strategies to envision money’s mediation” explores the work of visual artists who use money as a means to address financialization or its broader social and cultural conditions and ramifications. Fundamentally, it seeks to answer the question: why are so many contemporary artists drawn toward working with money, and why is so much of their work atrociously bad—conceptually lazy, aesthetically banal and theoretically infantile? The answer, I suggest (drawing on the work of Fredric Jameson, David Graeber and Randy Martin), stems from the fact that money is already an active mediation or “realabstraktion,” and its further dematerialization and financialization leaves many artists nostalgic for its material legacies. In examining the work of critical contemporary visual artists, I identify three strategies at play (in addition to a half-strategy of the blithe and insidious celebration of money’s power). The first, represented by the world of Barbara Kruger and the street artist Blu, is to use art’s residual romantic esteem to index money’s evils. The second, represented by artists like Christian Jankowski and William Powhida, is to turn the critical gesture inward, exploring the financialization of art itself. The final strategy, represented by artists Máximo González and Cesare Pietroiusti, is a more subtle but potentially more powerful strategy of revealing a secret affinity between money and art: both are power-laden forms of mediation, methods for reflecting on and manipulating the fabric of shared human cooperation.

The purpose of Chapter 2 “6 artists x 2 crises x 3 orders of reproduction” is to insist that the conditions for a radical artistic intervention in the field of money and finance are profoundly changed since the 1970s. To do so, it takes up the work of six radical artists working with money, three (Joseph Beuys, Hans Haacke and Lee Lozano) active around the crisis of 1973, three (Nuria Güell, Zach Gough, and the collective geheimagentur) in the decade following the financial crisis of 2007/8. Drawing on and expanding a conceptual apparatus I developed in Cultures of Financialization, these artists are plotted in terms of three “layers” of the capitalist crisis of reproduction: first, the fraught reproduction of capitalist circulation and profit itself, as theorized by Marx, Rosa Luxemburg and Louis Althusser; second, the reproduction of social institutions and identities as charted (diversely) by Pierre Bourdieu, Michel Foucault and Stuart Hall; finally, the reproductive labor of social life as explored by materialist feminists like Silvia Federici and Nancy Fraser. The chapter takes up art and finance as interwoven throughout the crises of these three realms of reproduction and their contradictions. It compares and contrasts the situations and strategies of artists in 1973 and today in these terms. Its overarching claim is that, while in 1973 it may have been possible to pose an artistic threat to capitalism in each distinct realm of reproduction, today no such clarity exists: radical artistic strategies need to be more cunning.

Chapter 3, “0 Participation: Benign Pessimism, Tactical Parasitics and the Encrypted Common,” explores money-art that mobilizes the tactics associated with the realm of what is heralded as social practice, relational aesthetics or participatory art. Rejecting the typical euphoria surrounding the socially benevolent impulses of this work, I echo the observation that the imperative to “participate” is germane to the logic of neoliberal financialization. For that reason, artists engaging such tactics need to be cognizant of their own participation in the reproduction of that order. But this should not be cause for despair or cynicism. Examining the work of six artists, I identify three subversive strategies. First, I call on the work of artists like the ensemble SUPERLFEX and Alex Stockburger are called to illustrate the strategy of benign pessimism, an inversion of Lauren Berlant’s theory of cruel optimism: these social sculptures, puncture the bubble of ever-deferred, poisonous anticipation that underwrites financialized reproduction. Second, I propose that the collective Robin Hood Minor Asset Management’s “hedge fund for the 99%” and the work of Paolo Cirio are examples of a strategy of tactical parasitics. Drawing on Michel Serres, I argue that such a strategy complicates our understanding of democracy and money by reframing the social order as the multiple enfolding of parasitic life forms without an originary “host.” Finally, I explore the minting of a speculative art coin, [Valentina] Karga and [Peterjohn] Gandy Invest in Themselves, and Cassie Thornton’s Give Me Cred alternative grassroots credit-reporting initiative as examples of a strategy of the encrypted common. Drawing on the work of Antonio Negri, as well as Jacques Derrida’s reinterpretation of the psychoanalytic concept of the crypt, I propose that these works stage a decryption of “the common,” which is both dead and alive within money and financial transactions

Chapter 4: “∞ Encryption: art’s crypt, securitization in numbers, derivative socialities” takes up and unfolds the theoretical term of the crypt introduced in Chapter 3, weaving together close readings of the works of three artists to expand our understanding of financialization now. It begins with Irish artist-researcher Mark Curran’s evolving exhibition THE MARKET, arguing that the artist’s pictures, collectively, reveal what’s hidden: that financialization has become the logic of capitalist totality, saturating society to such an extent that political agency seems impossible to locate. Social life is, in a sense, encrypted by money. Next we travel to Le Freeport in Singapore: the luxury art warehouse where countless cultural treasures lie encrypted; the inventory is unknown even to the building’s owners. This, I argue, is a key example of the infrastructure being built to ensure art’s financialization, and it has a lot to teach us about the “society of control” (Deleuze) of financialization being implemented in all sorts of social, economic, political and cultural spheres. Here opaque, shifting crypts and codes of access and denial are the norm. Yet, as I have done throughout the book, here I am keen to reject the idea that financialization is purely an elite and alien realm. I turn instead to the films of Melanie Gilligan and the theoretical work of Randy Marin to explore what the latter calls the “social logic of the derivative”: the way the fabric of everyday “sociality” is being rewoven by finance. Martin, for one, refuses pessimism, instead arguing that this presents new opportunities for radical social justice based not on a return to the fabled “security” of the post-war welfare state, but on new solidarities of mutual indebtedness. In the final section of this chapter I assess some of the collective artistic-activist projects that emerged from Occupy Wall Street—notably the anti-debt work of the Rolling Jubilee and the Debtfair ensemble—to seek out what this emergent form of solidarity within, against and beyond financialization might look and feel like.

The book’s conclusion “Towards abolitionist horizons,” attempts to sum up and recast a number of the core arguments that thread throughout this book, notably that money and art are the best of enemies and the worst of friends: in various ways these two forms of mediation and mutual encryption reflect and, indeed, support one another. As such, I restate my call for an abolitionist approach, this time explicitly engaging with the archive of abolitionist thinking that stems from the Black radical tradition. Here, I try and draw some inspiration and lessons from the struggle against prisons and other carceral institutions to offer some notions of what a politics that sought to abolish both art and money might look like. Ultimately, I suggest, this would be a matter of building and rekindling autonomous forms of cooperation, social reproduction and the radical imagination.