Opioids:

Capitalist Murder

A story of empire, racism and revenge

Published October 24, 2020

Revised December 30, 2021

The opioid crisis has claimed millions of lives...

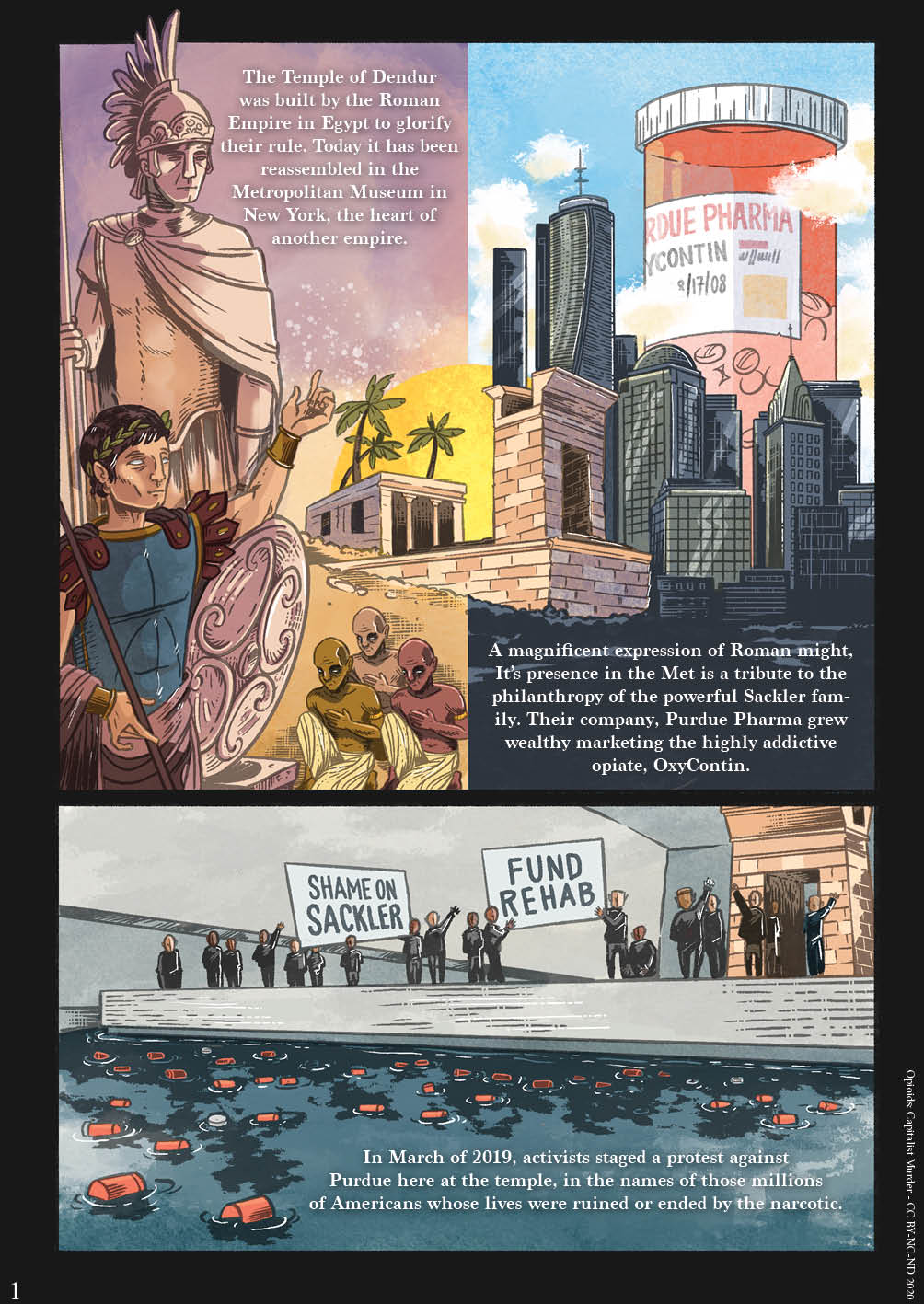

With profiteering corporations like Purdue Pharma and the wealthy Sackler family in the news, and with deaths from opioids climbing amidst the global pandemic, it’s time to revisit the longer history of drugs, empire and racism that underscore the current crisis.

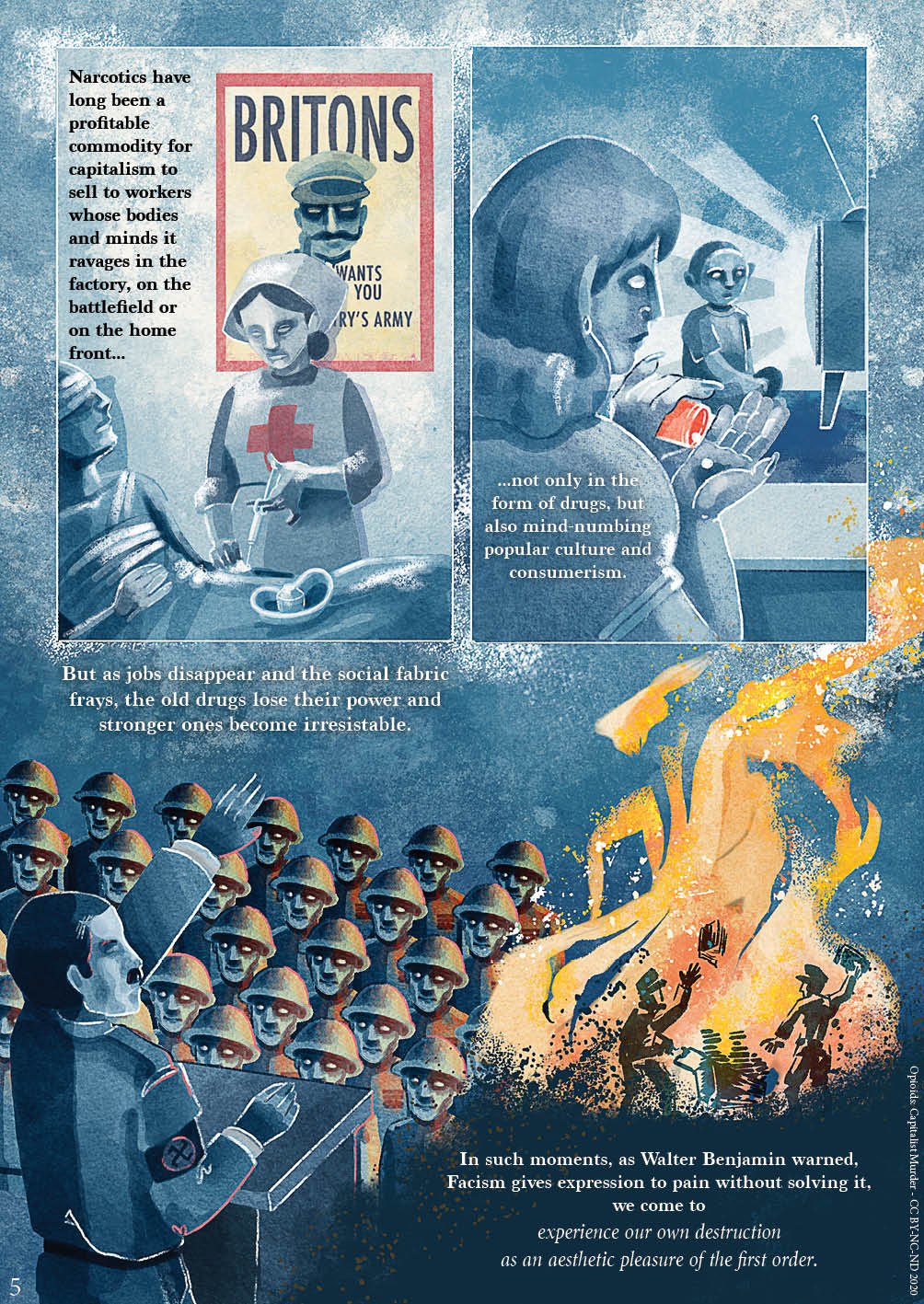

This short web comic, based on a chapter of cultural theorist Max Haiven’s Revenge Capitalism, draws the links between the opioid tragedy and the global system of racial capitalism that makes so many people disposable and uses racism and fascism to cover its tracks.

But it’s also a story of what happens when we fight back.

...this is one story of how we got here

Audio interview

In late 2019 author Max Haiven joined C.S. Soong of KPFA’s radio programme Against the Grain for a one-hour interview about the themes in this short graphic novel and the book chapter on which it is based.

Buy the Book

This is a graphic adaptation of the chapter “Our opium wars: pain, race, and the ghosts of empire” in Max Haiven‘s 2020 book Revenge Capitalism: The Ghosts of Empire, the Demons of Capital, and the Settling of Unpayable Debts.

The book is available worldwide in print and ebook formats from Pluto Press.

Credits

Produced by the RiVAL: The ReImagining Value Action Lab with AdAstra comix.

Written by Max Haiven and Hugh Goldring.

Illustrated by Pia Alizé Hazarika.

Based on the chapter “Our opium wars: pain, race, and the ghosts of empire” in Max Haiven’s book Revenge Capitalism: The Ghosts of Empire, the Demons of Capital, and the Settling of Unpayable Debts, published by Pluto (2020).

For more information contact: info.rival [at] lakeheadu [dot] ca

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which means you can download and share it freely but it cannot be changed or used for commercial purposes without permission.

Click on the images below for full screen and zoomable reading option.

Essay

Purdue pharma’s collapse will not answer the realities of racial injustice behind the opioid crisis

Max Haiven – Canada Research Chair in the Radical Imagination, Lakehead University

October 2020

On Wednesday the US department of Justice proudly announced a deal with notorious opioid manufacturer Purdue Pharma that would see the company plead guilty to three federal charges and pay over $8 billion to treatment and abatement programs to deal with the massive opioid crisis they helped unleash. The penalty will bankrupt the company whose assets will be sold off, including to a new public interest trust overseen by the government that will ensure powerful painkillers like its patented OxyContin will continue to be manufactured for the limited purposes for which it was originally designed: extreme and palliative cases.

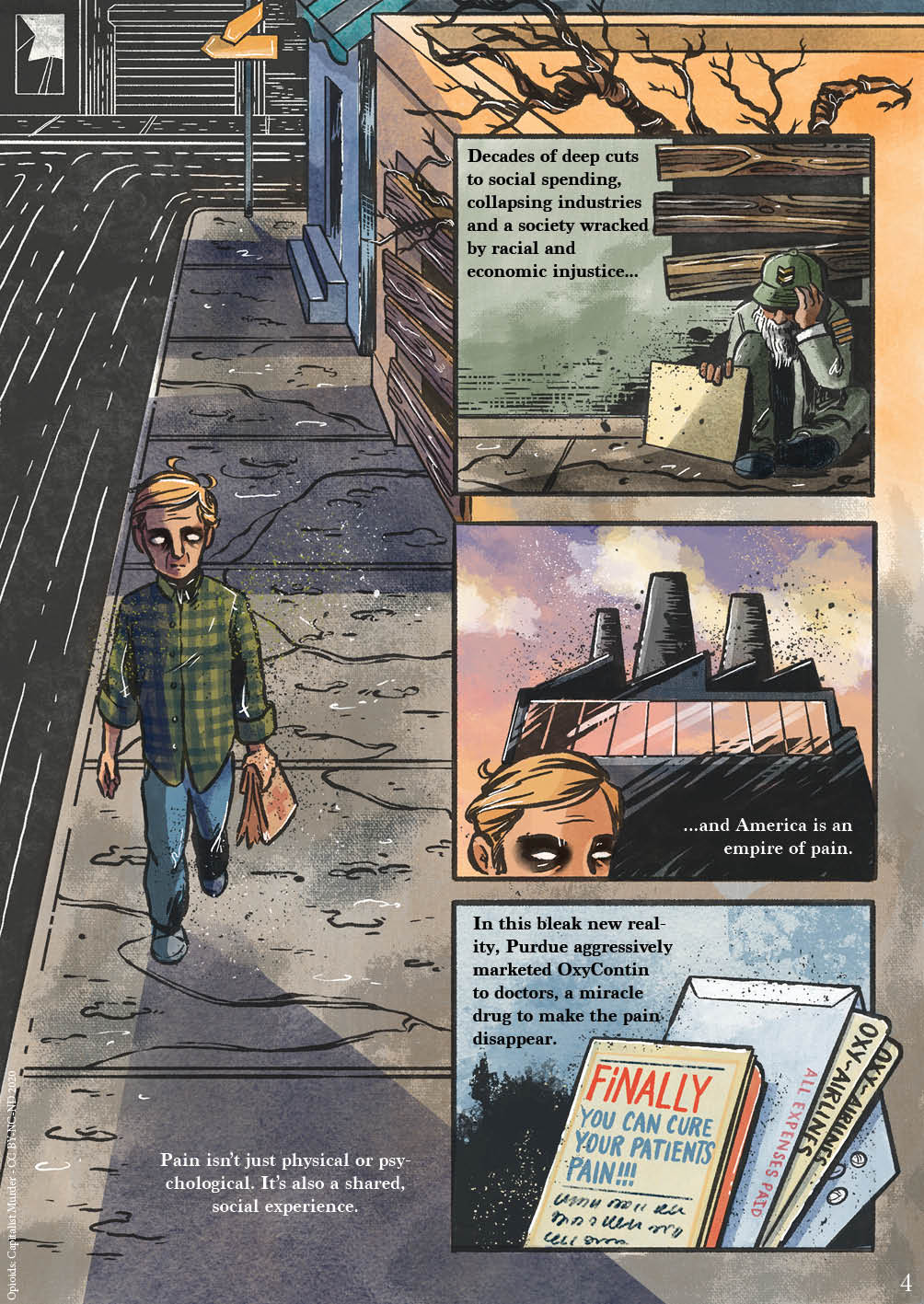

For the millions of Americans and people around the world whose lives have been ended or destroyed over the last two decades by the opioid crisis, this ruling may seem like vindication. Purdue (a company closely controlled by the Sackler family who grew fabulously wealthy from it) was pivotal to concocting friendly research, gaming federal regulations and seducing doctors and pharmacists to ensure that powerful narcotic was widely prescribed. They specifically targetted suburban, exurban and rural populations with high rates of disability, deindustrialization and alienation, contributing to a wave of so-called “deaths from despair” (from overdose, alcohol and suicide) that has blighted whole regions of American, notoriously Appalachia and the rustbelt.

Corporations like Purdue are weapons of a system of capitalism that sacrifices people’s lives and whole communities on the altar of profit, and such weapons are disposable because there are many more who will take their place.

But the sticker shock of an $8 billion fine should not mislead us from what’s really happening here. Corporations like Purdue are weapons of a system of capitalism that sacrifices people’s lives and whole communities on the altar of profit, and such weapons are disposable because there are many more who will take their place. For one, while Purdue is the most notorious corporate drug pusher in our moment, there are many others, many of them household name brands. For another, while the Purdue corporation may be dissolved, its beneficiaries and operatives, including the Sackler family and the executives who developed the company’s narco-terror strategy, will never face the music and, today and in the future, will enjoy their massive wealth in comfort. While I am all for governments seizing corporations that produce vital things (like drugs) and using them in the public interest, if this is indeed to be done we should also do so for all the other opioid manufacturers, as well as manufacturers of insulin, crucial cancer drugs and more.

The scapegoat

The reality is that, in this case, as much as I and many others are delighted to see the fall of Purdue, this corporation has been made into a scapegoat who, though guilty as sin, is made to serve to distract attention from the much greater number of firms, regulators, politicians, doctors and more who, together, helped create a situation where at very least half a million Americans perished and millions developed life-destroying drug dependencies.

Penetrating and bestselling journalistic accounts like Sam Quinone’s Dreamland and Macy’s Dopesick, as well as investigative journalism by Esquire and the New Yorker magazine reveal a tangled web of complicity where nearly every social institution turned a blind eye, accepted bribes or failed in its duty. With the pawn-sacrifice of Purdue, we will be encouraged to imagine justice has been served, when in fact the structural, systemic and institutional conditions that led to the crisis are not only still present, they have only become worse, and only in part thanks to the Trump administration’s gutting of the Federal government’s capacity to monitor and regulate corporations.

Yet as I argue in my recently published book Revenge Capitalism: The Ghosts of Empire, the Demons of Capital, and the Settling of Unpayable Debts and in a recently released web comic based on it, such political misdirection and scapegoating has a longer history, as too do the entanglements of capitalism, racism and narcotics, including opioids.

With the pawn-sacrifice of Purdue, we will be encouraged to imagine justice has been served, when in fact the structural, systemic and institutional conditions that led to the crisis are not only still present, they have only become worse

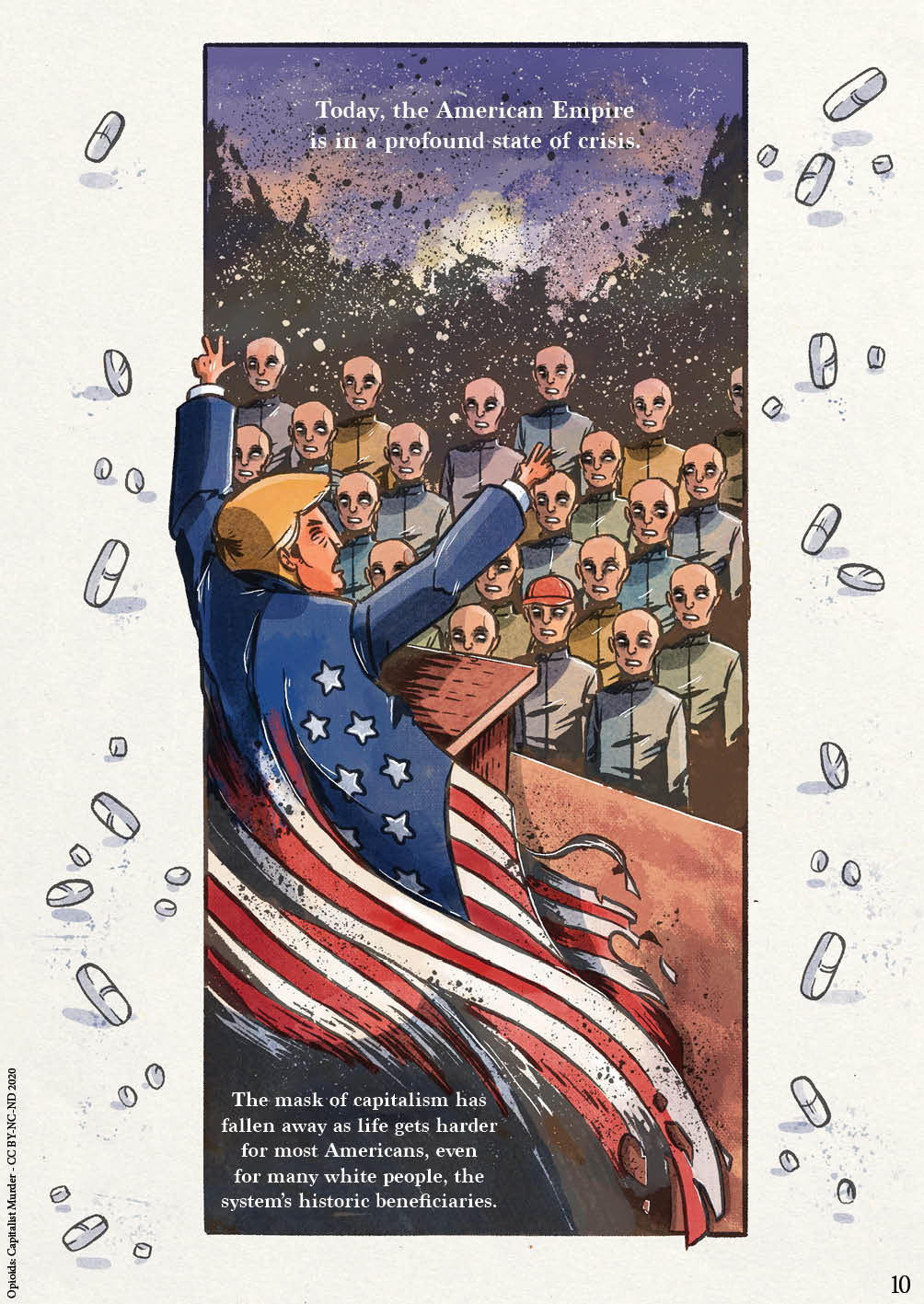

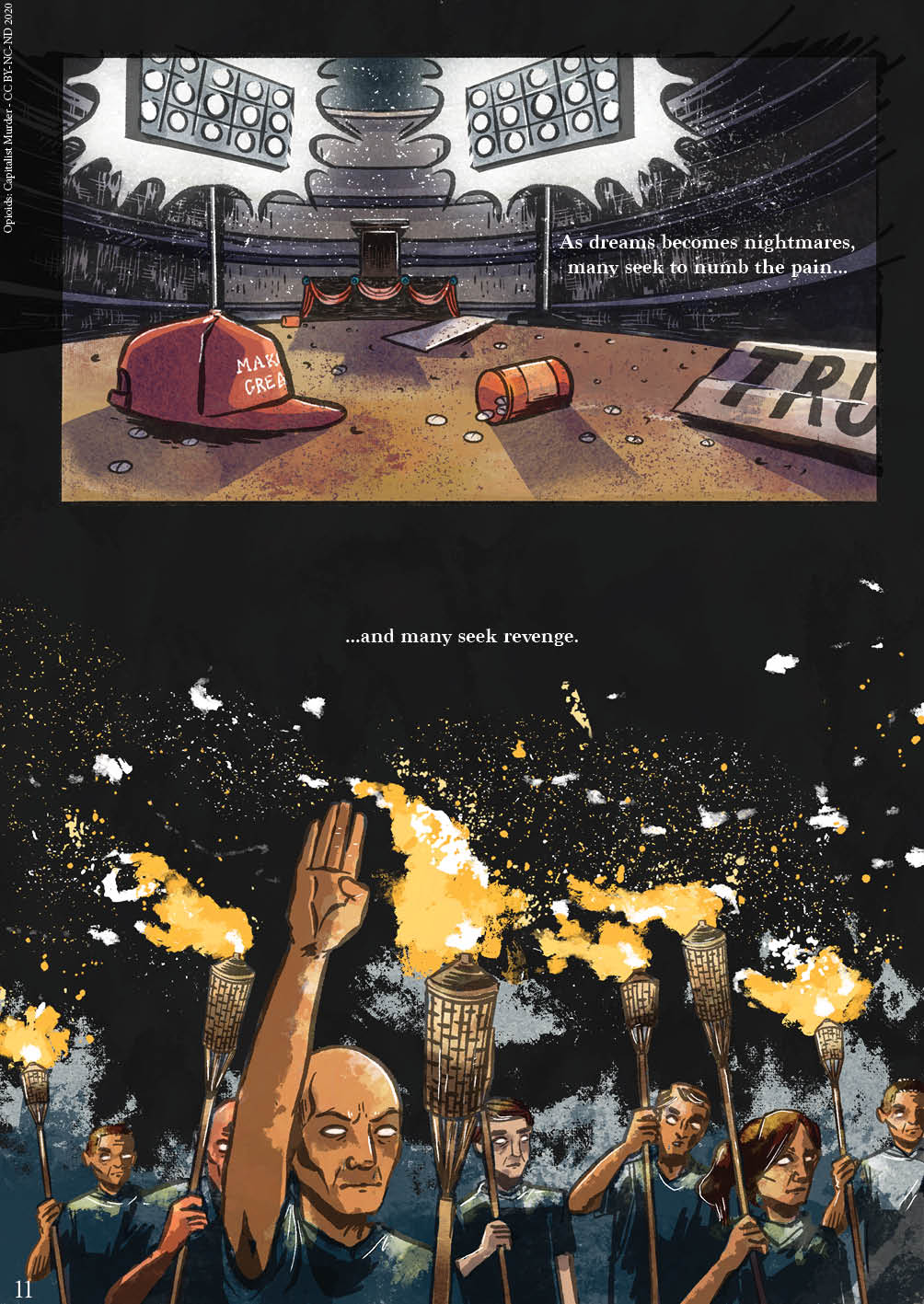

Shortly after Trump’s ascendancy to the presidency, demographer Shannon Monnat released a series of findings that showed that, in majority white counties (especially in the rustbelt and Appalachia) the strongest predictor of a shift in voters from Obama in 2012 to Trump in 2016 was the rise in “deaths of despair,” notably from opioids. This led some commentators to comment on the “revenge of the Oxy electorate“: disenfranchised white people angry at the way the drug, and the dire economy on whcih the drug preyed, had ruined their lives, families and communities.

All politics are complex, the politics of race in America all the more so. We need to be attentive to the alibis we make for revanchist whiteness: nothing excuses or justifies the turn of many white Americans towards a politics of fascistic racism and vengeful white supremacy, even though it has been a strong part (perhaps the strongest part) of American politics since the original colonies were founded on stolen Indigenous land and since the nation was built with enslaved African labour.

Still, attending to the political impacts of the opioid crisis is vital as we hover on the brink of another election where, on the one hand, Trump has used all the tools at his disposal to whip up white resentment and rage (even explicitly celebrating vigilante militias) and, on the other, the Democrats have elected to run on a conservative ticket that will likely mean that, if elected, life will simply get worse for most people as neoliberalism continues to run amok.

A longer story of race and drugs

In my book and the web-comic based on it, I try and tell a longer story to help frame our moment.

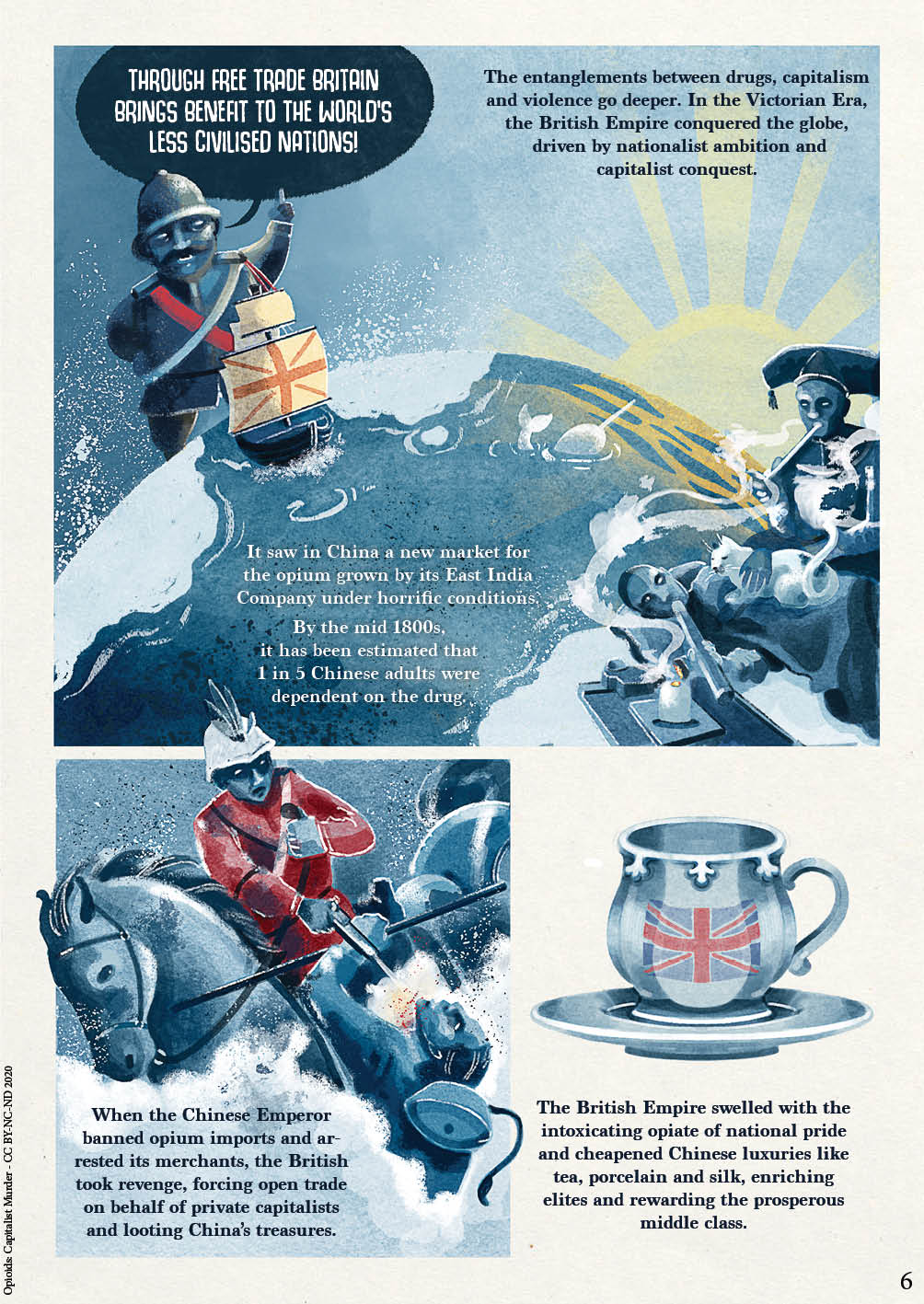

This is not the first major opioid epidemic. In the mid-19th century the British Empire (with help from wealthy Boston merchant and maritime families) forced the Chinese empire to open its ports to the importation of opium grown by the East India Company in India under brutal conditions. Faced with growing rates of addiction especially among the military and civil service, the Chinese emperor banned the importation of the narcotic and ordered its traders arrested and supplies destroyed. The British and their allies took this as a pretext for two short, devastating wars in the name of protecting the lucrative trading corporations.

The wars were justified in part through a racist rhetoric that held that Britain had the right, indeed the obligation, to “teach” the backwards Chinese a lesson about the liberal and democratic virtues of “free trade,” even if it meant war and suffering. The British narcoterrorist corporations, when questioned back in the British parliament (which had itself banned opium imports), espoused defences of the trade that eerily mirror the defences by Purdue and other opiate-pushing corporations in courts today: it’s not their fault if individuals “misuse” their legitimate product. Government interference would be tantamount to socialism. If they did not manufacture and sell the drug, some competitor would.

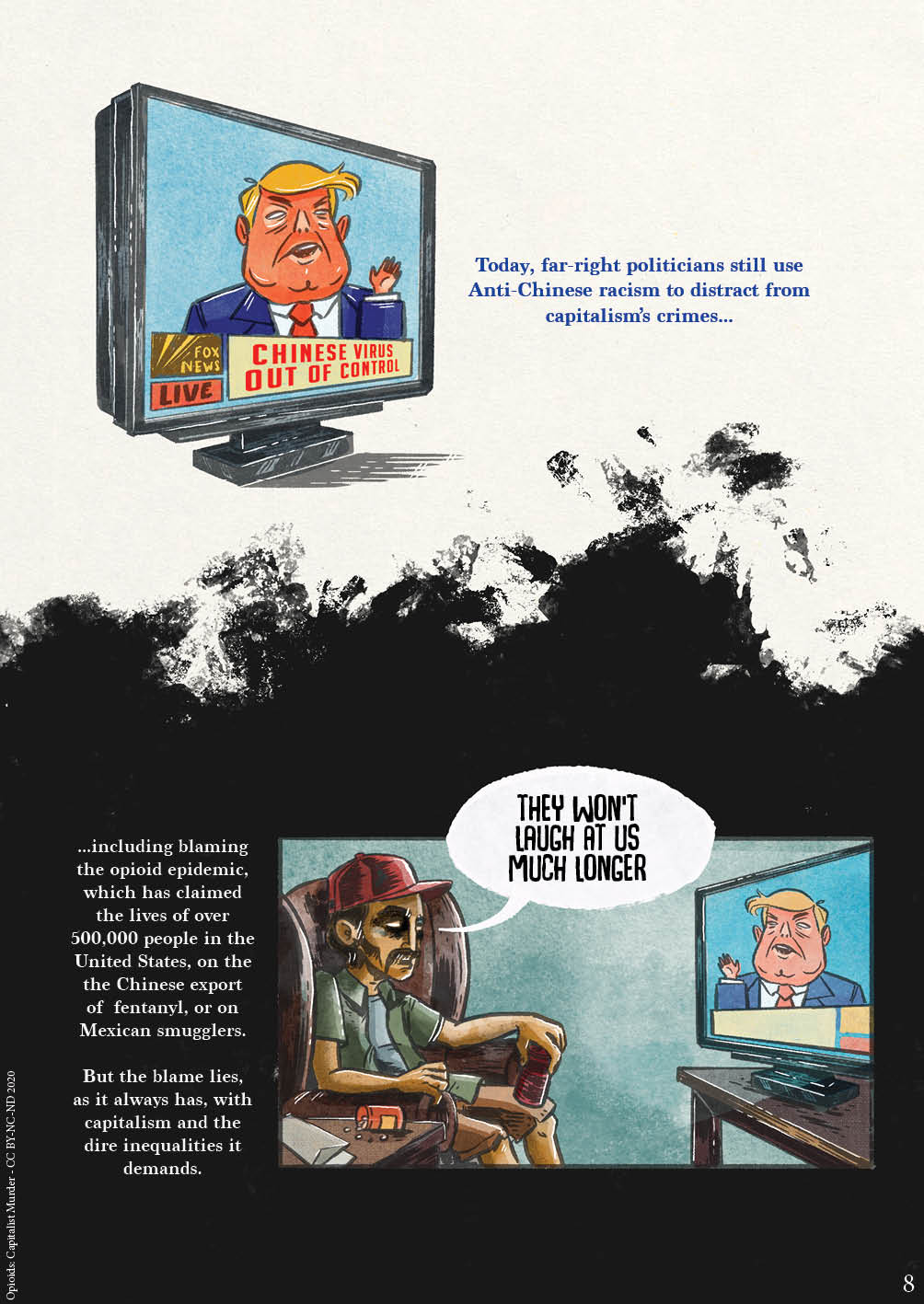

Today, Trump’s rhetoric of Covid-19 as a “Chinese virus” as well as his blaming of the opioid crisis on the Chinese export of fentanyl and the smuggling of drugs across the US-Mexico border, rehearse these old, racist myths, once again displacing the crimes of capitalism onto convenient “foreign” scapegoats.

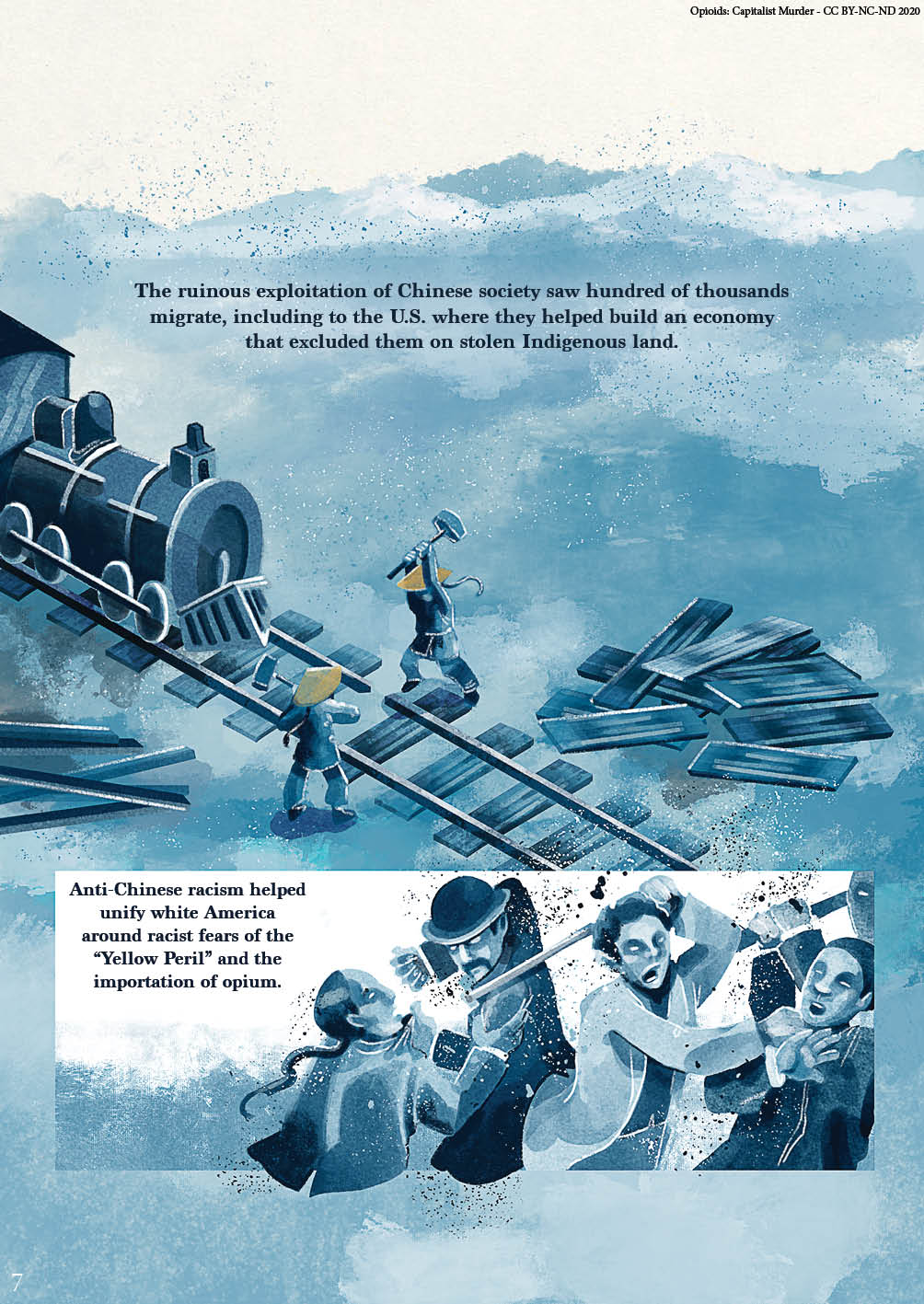

In the aftermath of the Opium Wars, Chinese society continued to suffer, leading to the exodus of millions of people, many of whom boarded ships as indentured servants and made their way to colonial settler states like the US, where, famously, they were put to the dangerous work of building railroads and other infrastructure for America’s westward expansion. As unregulated 19th century capitalism wreaked its vengeance on workers of all backgrounds, opportunistic politicians whipped up anti-Chinese racism as a way to divide the working class against itself, including by stoking fears that Chinese workers were using opium to sexually “enslave” white women. Likewise, anti-Latinx racism, even as early as the 19th century, was organized around racist fears of drug smuggling.

Today, Trump’s rhetoric of Covid-19 as a “Chinese virus” as well as his blaming of the opioid crisis on the Chinese export of fentanyl and the smuggling of drugs across the US-Mexico border, rehearse these old, racist myths, once again displacing the crimes of capitalism onto convenient “foreign” scapegoats.

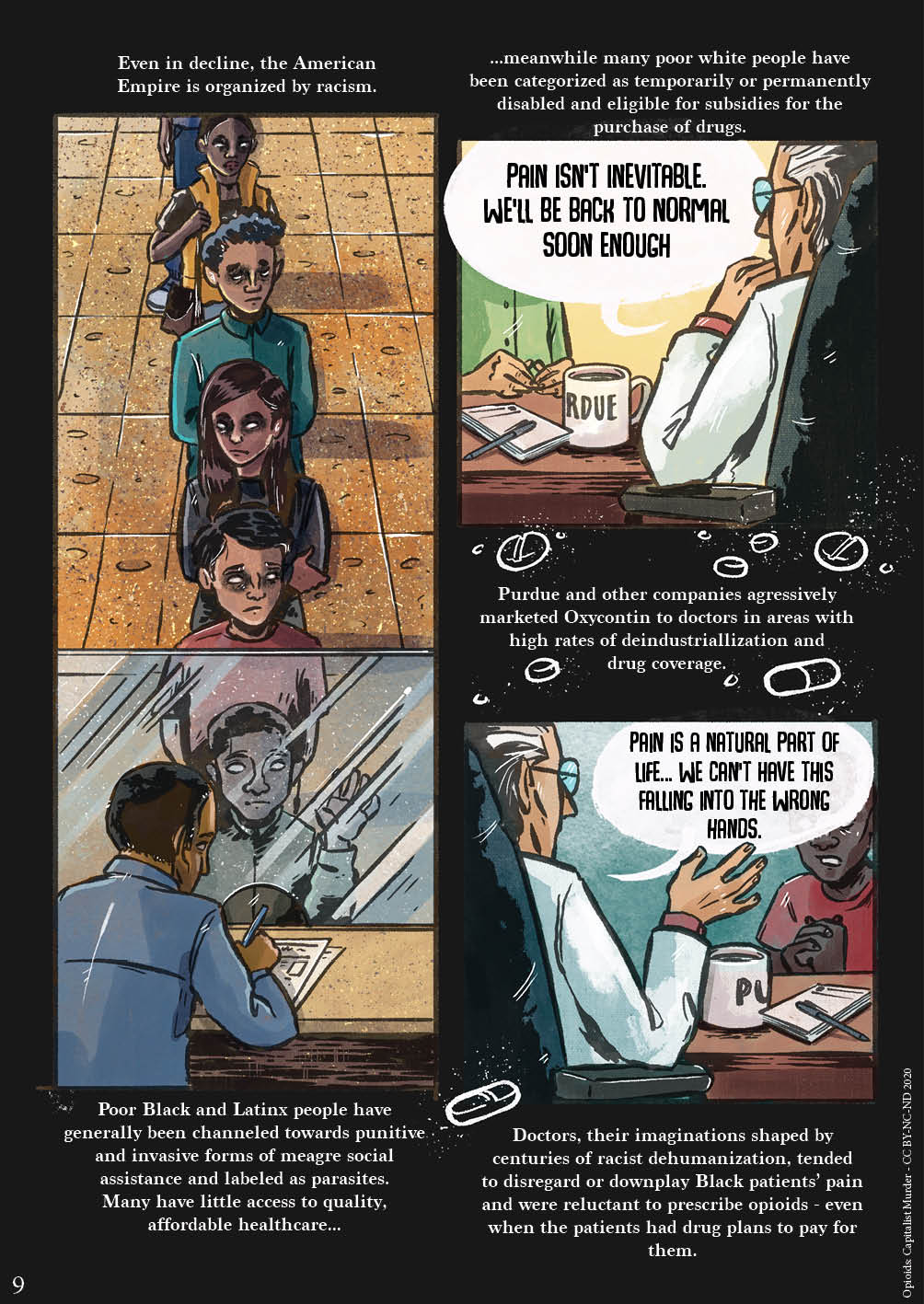

Trump is certainly not alone in his treatment of the opioid crisis as a sorrowful public health crisis affecting the salt-of-the-earth white heartland. This approach no doubt shaped by the fact that, at least in the news media, this opioid epidemic is presented as a scourge that disproportionately affects white people. (In fact, the opioid nightmare affects all communities in America, but compared to other public health crises that disproportionately impact racialized communities, this one has also hit white communities). Based on this perception, the opioid crisis has been treated much more sympathetically than other, past drug epidemics that have been made to appear as largely the problem of racialized communities: a previous wave of opioid use in the 1970s, for instance, of crack cocaine, or cannabis use. These have, as we well know, been used as justification for a merciless racialized “war on drugs” that has devastated many poor communities and contributed dramatically to the disproportionate mass incarceration of Black and Latinx people.

Yet all this and more is rendered invisible, largely thanks to the predictable failure of mainstream media to cover the story in any degree of complexity, as well as the opportunism of politicians of all stripes eager to find a quick scapegoat and avoid any meaningful change to the sick economy and society on which the drug preyed.

It is compounded by the cruel irony that the lower-than-expected rates of opioid use and dependency among Black patients is due in no small part to the fact that Purdue and other companies declined to promote the drug in Black majority areas, surmising that not enough residents had drug plans to cover their purchase. And even in cases where doctors had the option to prescribe opioids to patients they did so significantly less frequently for Black patients based on the (often unconscious) racist belief that Black people can (and should) suffer more pain or that Black patients were more likely to abuse or sell their prescriptions.

Yet all this and more is rendered invisible, largely thanks to the predictable failure of mainstream media to cover the story in any degree of complexity, as well as the opportunism of politicians of all stripes eager to find a quick scapegoat and avoid any meaningful change to the sick economy and society on which the drug preyed.

Accountability?

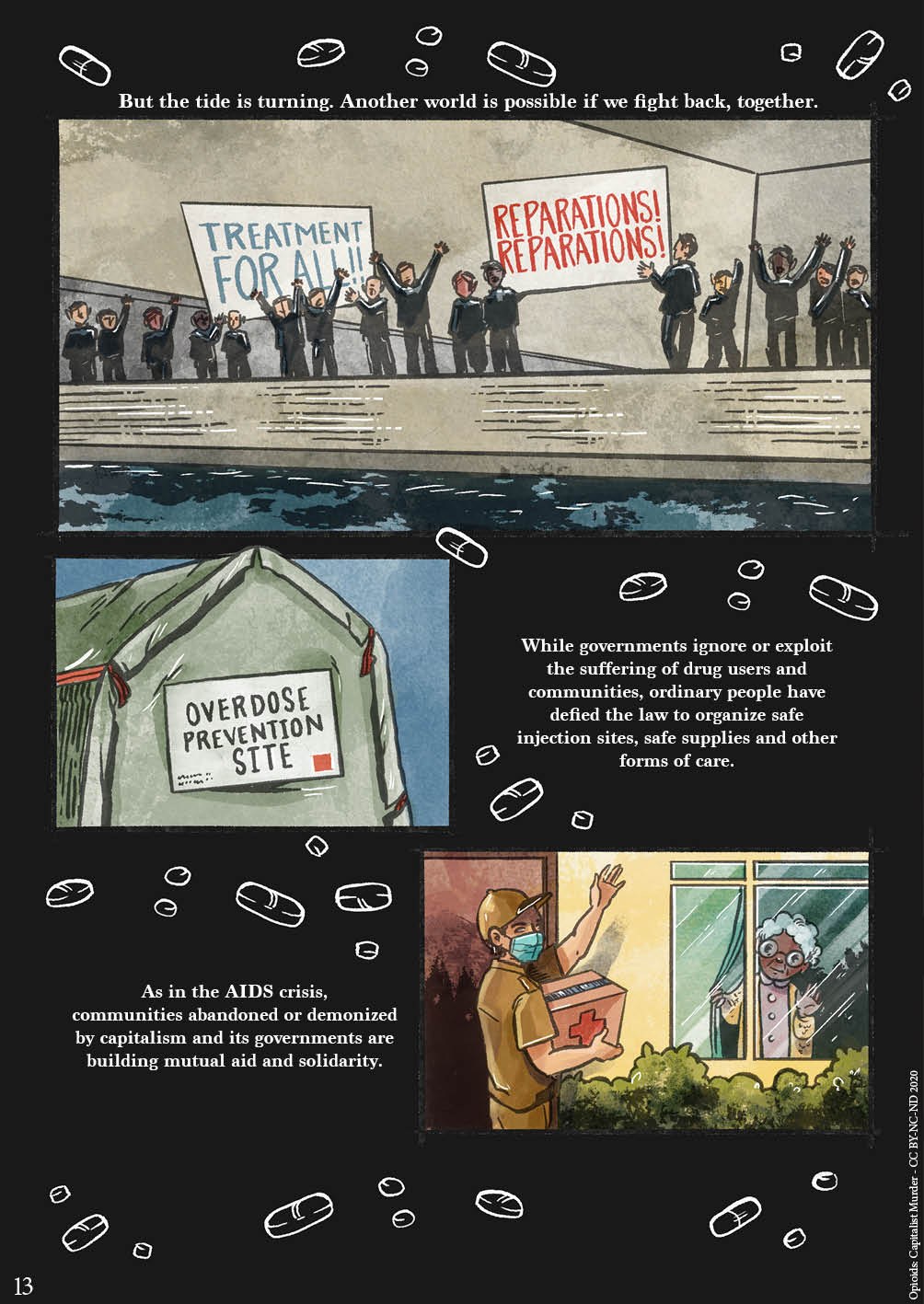

So the fall of Purdue is a small victory for those who hope for justice, but nowhere near enough to truly achieve any measure of accountability, let alone social change.

For that to happen not only the company itself but also its past executives, board members and beneficiary must be brought to account. More must be done to understand the roots of the crisis through a thorough inquiry into all the public and private institutions that failed, that looked the other way, or that actively benefitted from the opioid nightmare. Deeper still, true justice will require an accounting and atonement for the structures and systems of race, racism and capitalist exploitation that are the infrastructure on which this crisis was built.

True justice will require an accounting and atonement for the structures and systems of race, racism and capitalist exploitation that are the infrastructure on which this crisis was built.

Such an inquiry and atonement is obviously not on the cards this election. But it is being generated in the proverbial streets. Health workers, activists and drug users are organizing together to develop safe injection sites and other forms of harm reduction, even when it has been made illegal. Communities are demanding answers and services and rejecting the stigmatization of drug use and dependency. There is, I think, a growing awareness that capitalism is at its dead end, it’s “revenge” phase, as I put it. The stakes have never been higher, and, as ever, real political innovation and hope come from the grassroots.