This essay originally appeared on the blog of Pluto Press in September of 2018.

What is the Fate of Creativity Under Capitalism?

Max Haiven

I have a confession to make. I don’t really care about art.

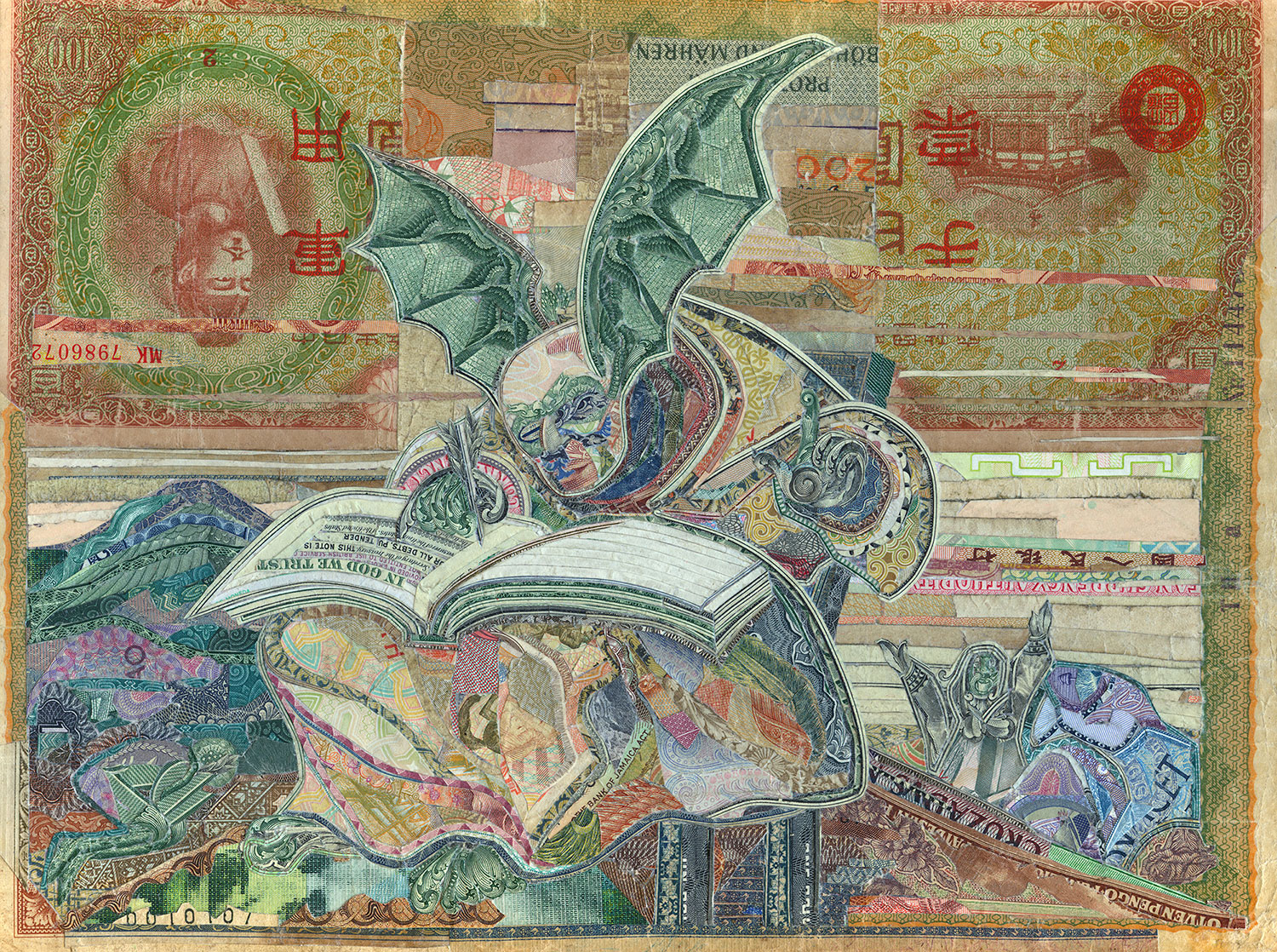

Art after Money, Money after Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization, is a book about how radical artists are responding to the financialization of society by incorporating money, debt, financial instruments and other aspects of the rapacious capitalist economy into their work. They do so as a method to hack, subvert, ironize, sabotage and exit financialization. But more generally it’s a book concerned with the fate of creativity and the imagination under this horrific system of exploitation and greed.

The reassuring myth is that capitalism merely vanquishes and stifles creativity and the imagination, and in many ways that’s true. Yet today, we’re living through an era when this economic system isn’t just turning us into mindless drones; it also demands we constantly exercise our cognitive, relational and imaginative faculties. For some of us, this takes the form of work in the so-called “cognitive” or creative industries, where our creative energies get harvested by corporations eager to corner the market on new products or techniques. For others, it simply takes the form of having to become ever more creative, imaginative and savvy in order to survive, juggling multiple part time precarious jobs and making ends meet in increasingly austere times.

The reason I’m interested in art is not because it somehow exists outside of this type of capitalism, but because it is intimate with it. Almost everything sacred or meaningful in this society has been commodified, monetized or financialized. Each of us today is tasked with transforming anything of value in our life into an advantage to be leveraged (hobbies, skills, friendships, education, housing, health and more), so we end up fetishizing “art” as somehow the last bastion of the soul, and so take great umbrage when we think of artists starving while billionaires spending oodles of money on canvases at auction.

Artists ought not to starve and the prices of art works are stupid. But focusing on these topics misleads us from deeper, more important questions. Artists ought not to starve because (a) no one ought to live in poverty and (b) everyone in society should have the resources, time and capacity to engage in creative expression, not just artists. Billionaires ought compete with one another to spend stupid amounts of money on famous works of art because (a) billionaires as such should be abolished (it’s fundamentally immoral and implicitly exploitative to allow such massive wealth disparities) and (b) because, if these works are truly so singularly aesthetically valuable, they ought to be held in the public trust so all of us can benefit.

My argument in general is that the concern of art’s financialization today, and the hand-wringing and pearl-clutching about the fate of the artists, is largely a convenient distraction from the deeper systemic issues that give rise to this condition in the first place. In Art after Money, Money after Art, I write about a number of terrifying and troubling new tendencies in the art market. For instance, the use of art as a vehicle to launder money, avoid taxes and place wealth offshore out of the reach of public scrutiny or redistribution. Or the rise of luxury freeports hyper-secure storage facilities, where the world’s uber-rich stash their ill begotten art loot, often leaving masterpieces in bunkers for decades simply to preserve their condition and avoid paying insurance fees while they wait for the resale price to rise. Often the owners of these works are not even individuals but newfangled corporate entities which pool the assets of many art investors to buy works purely for their speculative future value. The market supply of venerable works by Old Masters, Impressionists, and even modernists is dwindling as many enter into private or museum collections and, as a result, there is a rapacious speculative hunger for the work of still-living artists. Consequently, the magnitude of fast money sloshing around the contemporary art world has a massive effect on the aesthetic directions of today’s so-called creative geniuses.

Many of the artists and curators I spoke to while researching this book bemoaned the way that this lust for newness drives a kind of frantic incorporation of art’s margins, with yesterday’s outsiders, radicals and malcontents finding themselves inexorably drawn into institutions and economies that once excluded them, even (sometimes especially) if the work is explicitly mischievous exotic or provocative; these are qualities that many art collectors would like to imagine themselves possessing. One of the arguments in the book is this constant whirlpool of art, not coincidentally mirrors the maelstrom of high finance, which increasingly seeks to transform every aspect of society into a speculative field of opportunities directly integrated into accelerated global financial networks. In a strange way, the art market itself is a kind of portrait of the system of financialization, of which it is also a part.

It should be mentioned that this yearning for newness has done relatively little to counter another tendency in art markets to prefer the work of white men as vehicles for investment. While recently the art world has preened itself on finally paying some modest attention to the work of women, “non-Western” artists and people of colour, the reality is that, at auction and also in the exhibition halls of the major museums, these outsiders are still the sideshow for the main attraction: an endless parade of stereotyped “creative geniuses” that, funnily enough, look just like the boards of directors of the world’s major financial corporations or the membership rolls of the golf courses where they frolic, rich white men. This is part of a long history by which the patriarchal imperialist and colonial imagination furnishes itself with the notion of rich white men as the pinnacle of the capacity for the reflexive imagination to help retroactively explain and legitimate their brutal subjugation of everyone else deemed inferior.

All that is odious enough, and frankly, after a few years of studying the intersection of high finance and high art I am more than glad to be done this nauseating task. I’ve tried to steer clear of simply rehashing the depraved antics of art market insiders, I don’t want to feed the fire of narcissism and self-satisfaction that characterizes that world. I have no desire to call for and be part of attempts to correct, remedy or salvage “art” as we understand it today; I don’t think art is going to save us from ourselves. I’m pretty skeptical towards the idea that art somehow opens our minds to the problems of our society or makes us better humans. Were that the case, then one would perhaps expect that the billionaire collectors who acquire so much of it would have some sort of crisis of conscience. Evidently, there’s little risk of that happening.

But why do we want to believe in art? What do we get out of our faith in it?

My argument in the book is that, so long as we fetishize art in this way, a fetishization that encourages us to imagine art is diametrically opposed ton money (in spite of so much historical and contemporary evidence to the contrary), we lose sight of the bigger picture.

Instead, I propose the following. If we bring art and money into an uncomfortable proximity to one another, especially if we do so by looking at the work of radical artists using money in their work, we might realise two vital things. The first is that art has never been free of money’s influence. Ever since “art” as we know it emerged (more recently than you might think – really only in the 18th century) it’s been tangled up with the desires of the wealthy and has served in their reproduction. And if that’s true, then maybe art actually has a lot to teach us about capitalism.

Today, for instance, the way art is financialized can demonstrate quite a bit about how types of work and spheres of life are transformed into speculative assets. The way artists become reframed as “investors” and “entrepreneurs” in this economic moment has a lot to teach us about what’s happening to everyone, not just artists. The way that even the most radical and provocative artworks are transformed into speculative commodities has a lot to teach us about the state of struggle today. In other words, looking at art and money under financialization can teach us a great deal about the fate of creativity and the imagination much more generally in this moment.

Meanwhile, on the flip side, looking carefully at the line between art and money also reveals that, though our neoliberal masters may insist “the economy” is the realm of cold rationality and calculative reason, the reality is that this and all economies are highly imaginative. Somehow, we live in a world where the hallucinogenic wealth of the City or of Wall Street has terrifyingly real power over the lives, the work, the food supply, the poverty, the climate and the fate of billions of people. But beyond the antics of the financial “artists” who concoct ever more “creative” and abstract masterpieces for making money out of nothing or extracting rents from the world the rest of us, there is a deeper question too: derivatives contracts, which represent a huge share of all globally circulating wealth may be “imaginary.” But so are all economic constructs, after a fashion. “The economy” is the name we give to the way we humans imagine our material relations to one another, the way we coordinate our cooperative energies. Today, that economy is hyper-coercive, atrociously banal, and ultimately suicidal, even if it claims to maximize our opportunities for entrepreneurial innovation and imagination.

What other economies might we be able to imagine and enact? How could we make creativity one of the defining values of society itself, not simply as a method of survival, but as a grammar of the care and abundance that is our common birthright? Although art has limited powers, it can help us think more creatively with these urgent if slow questions.