This review of Review: J. Lorand Matory’s The Fetish Revisited: Marx, Freud and the Gods Black People Make will appear later this year in the Journal of Cultural Economy.

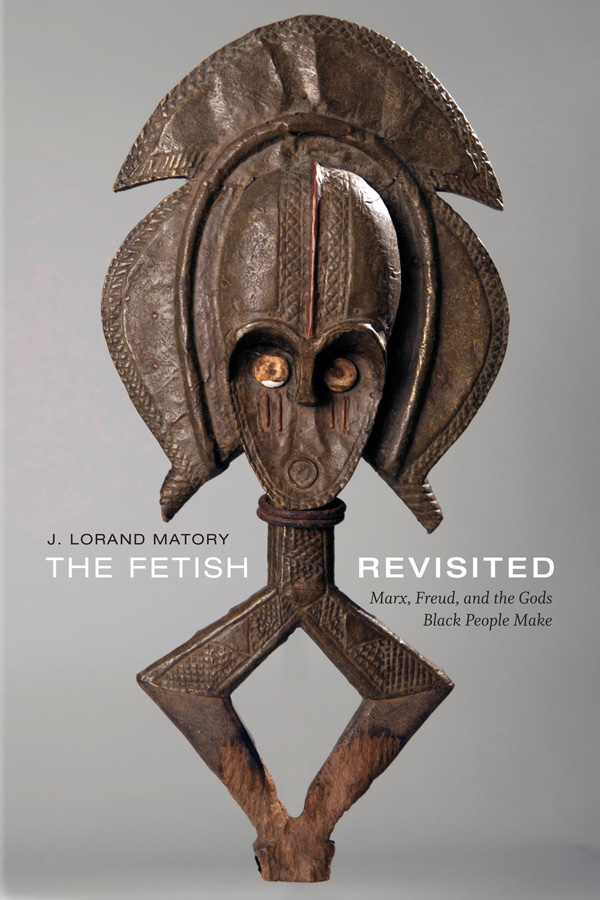

Review: J. Lorand Matory’s The Fetish Revisited: Marx, Freud and the Gods Black People Make

Max Haiven (Canada Research Chair in Culture, Media and Social Justice, Lakehead University)

The notion of the fetish is commonplace in conversations at the intersections of cultural studies and political economy. Yet the term often goes undefined, used as a shorthand for an irrational belief or fixation. For those working in the Marxist tradition, fetishism names that dangerous mystique that clouds an understanding of commodities and the relations of capitalist exploitation from which they spring. For those in the Freudian tradition, the fetish is the residue of a hiccup in the development of the individual’s libidinal economy, a pathological (though often harmless) obsession where objects, body parts or practices become the sources of or prerequisites to pleasure. In common parlance today, the “fetish” names a popular and lucrative catch-all for “kink” sexual practices or an unhealthy obsession with a false idol.

J. Lorand Matory’s The Fetish Revisited shows us that much more is at stake in the term The very idea of the fetish stems from a self-aggrandizing European discourse through which the diverse material practices of non-European civilizations were cast down as childish and primitive. Matory directs the anthropological gaze back on Europeans who made a fetish (an object endowed by the human imagination with supernatural power) of the very idea of the fetish. Beyond simply a critique, his text is also a singularly insightful, thoughtful and provocative engagement with the present-day practitioners of traditional West African religions whose ancestors’ practices were so fatefully misrecognized as mere “fetishism” by Europeans. Matory’s bold revisitation of the fetish will be important for moving the cultural study of economics and the economic study of culture beyond Eurocentric presumptions and teleologies.

Like the looted artifacts of the non-European world that are still today put on display in European and North American anthropological museums as evidence of their original owner’s barbarism (and of their current custodians’ benevolence), the notion of the fetish is itself stolen and made, retroactively, to justify the conditions of its theft

The notion of the fetish emerged in European theory as early as the 15th century based on a fundamental misunderstanding of West African cultural practices. Like the looted artifacts of the non-European world that are still today put on display in European and North American anthropological museums as evidence of their original owner’s barbarism (and of their current custodians’ benevolence – see Hicks 2020), the notion of the fetish is itself stolen and made, retroactively, to justify the conditions of its theft. When the Catholic Portuguese and, later, the Protestant Dutch, began to expand their empires from the 15th century onward, they encountered and developed trade relations with West African civilizations whose cosmologies were vastly different, but whose complex and nuanced spiritual practices threw European’s strange fixations into stark relief (Pietz 1985). As David Graeber (2005) has argued, when met with the exotic customs of West Africans, European were faced with the provincialism of their own weird spiritual customs. As Anne McClintock (1995) notes, This jarring experience led Europeans to invent the kind of universalist ideals of human development that would become the key legitimations for imperialism, notably in the myths of civilizational stages and racial hierarchy. These were given scientific gloss in the 18th and 19th centuries and still haunt us today, with tragic effect. But back in the 15th century, the notion of the fetish, based on a word borrowed from Yoruban cosmology, would become a convenient catch-all by which European travelers, traders, missionaries–and, later, anthropologists, scientists and colonial administrators–could defame all the vast range of non-European spiritual practices involving objects, practices Europeans deemed barbaric, infantile, misguided or perverse. Matory argues, brilliantly, that the notion of fetish was itself a kind of fetish for Europeans: an almost supernaturally powerful “word-weapon.” Through its discursive magic non-European cosmologies could be denigrated as fetishistic and Europeans could develop their own cosmology of supremacy that would, by the 19th century, resolve itself around the fetishistic notion of whiteness.

Matory traces a genealogy of the concept of the fetish through European thought, including its role in the emergence of anthropology (his own field) and philosophy (notably Hegel). But Matroy takes special aim at the two thinkers with whom the term is now firmly associated: Marx and Freud. Through an engagement with both thinkers’ complex biographies, Matory notes that these Germanophone Jewish intellectuals (both of whom died in London as what we would today call refugees) were struggling to find a place within a highly anti-Semitic cultural climate of capitalist imperialsm. Through a process Matory calls “ethnological schadenfreude” (by which upwardly mobile actors in a racial hierarchy secure or elevate their acceptance and belonging within the dominant paradigm by proverbially throwing those below them under the bus), Marx and Freud, independently of one another, drew on and reproduced a racist notion of the fetish as a means to both critique and also establish a place within the European intellectual canon. This analysis alone is worth the price of admission: Matory’s reading of the lives and ideas of these foundational thinkers is lucid, illuminating and convincing. The Fetish Revisited represents the best of the kind of anthropological work that turns its attention back on the cosmology and culture of the colonizer. It is not only a deconstructive critique but also opens new horizons for how we imagine and contend with the work of crucial thinkers.

Matory, for instance, draws on the work of Peter Stallybrass (1998) to note Marx’s anxieties about his ability to survive in London and raise his children in a bourgeois household, free from the stigma of his Jewish ancestry. To do so, Marx depended on his brother-in-arms Engels’ largess, which the latter could afford thanks to his family’s ownership of Manchester textile mills spinning cotton from the slave empire of America. Yet the Black subject and the regime of slavery on which Marx literally, materially depended is barely mentioned in his work, relegated to a footnote in Capital. And what are to make of Marx being literally surrounded by the stolen “fetishes” of the world’s non-European civilizations as he wrote Kapital in the central reading room of the British Museum?

Through a process Matory calls “ethnological schadenfreude” (by which upwardly mobile actors in a racial hierarchy secure or elevate their acceptance and belonging within the dominant paradigm by proverbially throwing those below them under the bus), Marx and Freud, independently of one another, drew on and reproduced a racist notion of the fetish as a means to both critique and also establish a place within the European intellectual canon

Matory likewise observes that Freud was fixated on his role as the patriarch of psychoanalysis: a largely homosocial order of secretive specialists that Freud orchestrated through gifted objects, notably intaglio rings. This is to say nothing of the doctor’s obsessive collecting of the (often looted) spiritual objects of non-European civilizations that adorned his office, still to be seen to this day in situ at the North London museum at his final place of residence. There is no doubt these objects inspired his work, notably his book with the widest impact beyond psychoanalysis: Totem and Taboo.

Both theorists, in a sense, rely on invisibilized Black labours and, at the same time, draw on and redeploy the colonial and racist notion of the fetish. Marx delights in wielding the word-weapon of the fetish to demonstrate how, far from the bastion of enlightenment, progress and reason, capitalism is, at its core, organized around the fetishism of commodities (with money as the jealous chieftain of that pantheon). Capitalism, which proclaims itself the apex of civilizational progress, is just as barbaric, bloodthirsty and brutish as his contemporaries assumed were the African “savages” on whose customs the notion of the fetish was based. Freud’s theory of the unconscious depends on a similar maneuver: darkly astir in the deep recesses of even the most civilized European is an “inner Africa,” a savage remainder, the id, that cannot ever be transcended, only tamed and restrained by the civilized development of the ego. Freud’s contemporaries believed the taming of the id was something of which “primitive people” were largely incapable and at which Europeans excelled, except in the case of pathological fetishists.

Matory is neither a Marxist nor a Freudian and worries aloud that adherents to these academic kinship groups will take offense at his materialist approach and psychoanalysis of their revered (dare we say fetishized?) ancestors. Fear not: Matory assures us that he comes not to bury them but to praise them, at least half-way.

Ultimately, Matory is interested in Marx and Frued not only as the notable critical theorists of the fetish but also as European thinkers striving to understand the triangular relationship between people, societies and things. He agrees with the general thrust of Bruno Latour and the New Materialists that we must contend with the agency of non-human (more-than-human) things. But whereas Latour et al. derive their position from a critique of European traditions (including, notably, those of Marx and Freud) that present the Enlightenment subject as the only true historical agent in the world, Matory advances from what he frames as “Afro-Atlantic thought”: the very source of the misunderstood notion of the fetish.

Roughly half of Matory’s book is a deep engagement with the way objects — ”fetishes” — function in the spiritual practices and cosmologies of Yoruba-Atlantic religions of West Africa and the Black diaspora. Yoruba-Atlantic religions continue to be practiced by millions of adherents today, despite the transatlantic slave trade, the influence of Christian and Muslim missionaries, the colonization of West Africa and a pervasive anti-Black world system. In addition to archival materials, Matory’s study draws on decades of interviews, conversations and debates with contemporary priests and initiates of these Yoruba-Atlantic faiths in their diverse manifestations in Nigeria, the United States, Haiti, Brazil, and Germany. Matory is also a professional collector of these spiritual artifacts, and deeply personally faithful to them.

Matory’s position gives him unique insight. He is a lauded and established self-reflexive Western anthropologist and cultural theorist at an elite private American university (Duke), a skeptical practitioner of Yoruba-Atlantic spirituality, an ambivalent collector of its artifacts and a Black citizen of the United States whose ancestors were enslaved and whose thought and whose experience has been shaped within the regimes of anti-Black racism.

Yoruba-Atlantic are theorists of the triangular relationship between individuals, societies and things just as much as Marx or Freud were; likewise Marx, Freud and other European theorists were both adherents to and in a sense priests of a Eurocentric cosmology that sought to explain this triangular relationship

From this complex and contradictory space Matory advances what stands as this book’s pivotal argument: priests of the Yoruba-Atlantic are theorists of the triangular relationship between individuals, societies and things just as much as Marx or Freud were; likewise Marx, Freud and other European theorists were both adherents to and in a sense priests of a Eurocentric cosmology that sought to explain this triangular relationship. What has hitherto stood in the way of understanding this parallel work of Yoruba-Atlantic priests and European theorists is the notion or “word-weapon” of the fetish through which European theorists at once defamed their Afro-Atlantic peers as superstitious savages and masked their own participation in a cosmology that fetishized whiteness.

And yet when stripped of its inherited defamatory and reductionist meanings, when we return to explore what the priests and initiates of Yoruba-Atlantic religions actually use and think of “fetishes,” a very different picture emerges. Those objects that Europeans mistook for “mere fetishes” are, in fact, complex, evolving, living and creative products by which people make sense of the complex social forces of which they are also a part. Yoruba-Atlantic “fetishes” are, in other words, theoretical concepts, just as much as the falling rate of profit or the Oedipus complex. Or, if you prefer, these famous theoretical concepts are also fetishes that both draw on and reproduce a broader cosmology for making sense self, other and relationality in a changing world.

Matory’s analysis of the diversity and nuance of Yoruba-Atlantic faiths and practices is astounding, but beyond my capacity to review and too rich to detail here. For our purposes it is worth noting how, equipped with his broader insights, he is able to stage a fruitful dialogue between the Yoruba-Atlantic priests and Marx and Freud in the book’s concluding pages.

Marx historical materialism concerns itself with the ways that humans always live in relationship to the objects they create. But Marx wields the word-weapon of the fetish to describe how we learn to forget the origins of objects in our shared labours and, instead, treat them as god-like totems with their own inherent powers. Yoruba-Atlantic priests, by contrast, believe/theorize that people and communities are defined through manifold relationships of material and symbolic exchange and trade with kith and kin, as well as with a diversity of nearby and distant others. Objects are the residue of these exchanges, and so are sacred, especially when they represent difficult, ambiguous or ambivalent relationships – in other words, encounters of difference.

Likewise, the Yoruba-Atlantic priests Matory interviews and convenes with certainly agree with Freud that the human subject is animated by multiple spirits of which they are unaware, but would balk at the idea that they number only three: the id, the ego and the superego. Matroy explains that Yoruba-Atlantic religion sees the subject as animated by dozens of spirits, including shared gods, family gods, ancestors and mythological figures. Yoruba-Atlantic priests and initiates use “fetish” objects to honour, communicate, placate, encourage, discourage, bribe or protect themselves from these spirits, as need be, all the while recognizing that each person is subject to forces beyond their control. Freud saw libidinal cathexis towards objects (as well as, let us recall, towards members of the same gender) as a pathological deformity in the proper development of the subject. According to Matory, Yoruba-Atlantic priests and practitioners mobilize objects as a much more community-oriented mechanism for producing and maintaining what Freud would have called sanity: the ability to function in a socially acceptable way in a complex world at the triangular intersection of individuals, societies and objects.

Matory is not suggesting that theory and religion are the same thing: each has its advantages and disadvantages, its own risks and rewards, its own anthropological context. Just as Matory applies his critical scalpel to the pathologies and dangers of European theory, he also admits and analyzes his discomfort with many of the spiritual and cultural practices of the Yoruba-Atlantic priests he studies. In the case of both his cosmologies (European-theoretical and African-spiritual) he notes that the profound insights these theorists/priests offer must be taken along with the profound violence they can enable or justify.

Matory’s approach gives us fresh resources through which we can revisit the concepts of Marx and Freud, not simply to rehearse their vices as Eurocentric humbugs but as the complex and ambivalent racialized products of a capitalist-imperialist-patriarchal Europe grappling, materially and ideologically, with its encounter with the world.

While a work of anthropology, the importance of Matory’s book is important for those of us interested in the interdisciplinary study of cultural economy. The book stages an important conversation between three European schools of thought with which many of us are familiar (Marxian, Freudian and New Materialist) along with, and inflected by, one of which the vast majority of us are woefully ignorant: Yoruba-Atlantic thought. This conversation has incredible potential and not only as the field of cultural economy seeks to move beyond its original Eurocentric focus and explore the complexities of the world. Matory’s approach gives us fresh resources through which we can revisit the concepts of Marx and Freud, not simply to rehearse their vices as Eurocentric humbugs but as the complex and ambivalent racialized products of a capitalist-imperialist-patriarchal Europe grappling, materially and ideologically, with its encounter with the world.

The collapsing of Marx and Freud’s projects is worrisome to those who inherit these traditions. I am among those who still see the profound potential for Marxist theories to contribute to both an analysis of capitalist society and a project of liberation. While I do not share the same optimism about Freud, many do, including Slavoj Žižek (1989) who also encourages us to embrace rather than eschew the fetish, albeit in a very different way than Matory. If taken to one extreme, Matory’s analysis might encourage us to apply Yoruba-Atlantic cosmology (or perhaps any cosmology) to state economic planning, or to formalize academic devotion for Marx or Freud into an actual religion. Having argued that the European “theory” summons itself into existence, materially and historically, through the defamation of African “cosmology,” we are left perplexed as to if there ought to be a line between concepts and, if so, where to draw it.

Though it is not Matory’s stated objective, The Fetish Revisited demands that we fundamentally reevaluate the origin of the tools we use to understand the relationship between culture and economics, between the making of meaning and the creation and exchange of things. By asking us to place the evolving and dynamic thought and practices of Yoruba-Atlantic priests on the same pedestal as our reverend theoretical forefathers (or, better, remove the pedestal entirely) we are compelled to undertake a more worldly consideration of the many ways we make sense of the relation between culture and economy. He is certainly not the first anthropologist to do so, but he does it with great skill.

At stake in Matory’s approach to the fetish, then, is not merely a critique of Eurocentric thought or a redemption of Afrocentric thought. It is a call to think the economic subject anew, not only to understand our motivations, vices and frailties but also the profound power we have to shape our world as it shapes us. Which, in a sense, was at the core of both Marx and Freud’s projects all along.

References

Graeber, D., 2005. Fetishism as social creativity. Anthropological Theory, 5 (4), 407–438.

Hicks, D., 2020. The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence. London and New York: Pluto.

McClintock, A., 1995. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest. London and New York: Routledge.

Pietz, W., 1995. The Spirit of Civilization: Blood Sacrifice and Monetary Debt. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 28, 23–38.

Pietz, W., 1985. The problem of the fetish. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, 9, 5–17.

Stallybrass, P., 1998. Marx’s Coat. In: P. Spyer, ed. Border Fetishisms Material Objects in Unstable Spaces. London and New York: Routledge, 183.

Žižek, S., 1989. The sublime object of ideology. London and New York: Verso.