My essay on endangered whales attacking boats in the Strait of Gibraltar has been published by ROAR Magazine here and below.

Here is also an audio version:

Last week wildfires raged mercilessly on America’s Pacific coast and the Gulf of Mexico continued to endure an almost unprecedented frequency of hurricanes and tropical storms. But it was across the ocean, in the Strait of Gibraltar, that we saw one of the most dramatic and tragic examples of capitalism’s climate chaos: a gravely endangered community of orcas attacking boats, as if in a coordinated but reckless fury.

Scientists who have dedicated their lives to studying this hyper-intelligent whale species are baffled and alarmed at this highly unusual behavior. They have risked a cardinal sin of biology: attributing human-like (anthropomorphic) explanations to animal behavior, describing the animals as “angry,” “pissed off” and even vindictive.

The orcas have every reason to be: their habitat has been interrupted by increasingly busy global shipping lanes. In 2014, the 13 kilometer-wide strait which separates the European and African continents, saw over 110,000 vessels representing half of the world’s maritime trade, a third of its oil and gas and 80 percent of the goods and gas consumed by the EU passing through its waters.

On top of the massive disturbance of gargantuan tankers, the orcas have other problems. Bluefin tuna fishers from Spain and Portugal resent the onerous and costly measures they are forced to take to protect the endangered whales. They often look the other way as fishing lines and nets ensnare or injure the animals, or use various weapons to scare them off their prey.

These and other factors — warming and acidifying oceans, for instance — have affected the orcas for years, diminishing their local population to a mere 50 souls. But it seems to have been the uptick in ocean-going traffic amidst the relaxation of lockdown, notably the return of pleasurecraft and ferries, that has driven the orcas to what appears to many observers to be a kind of suicidal vengeance. They are coordinating ramming attacks on ships much larger than them, even conscripting precious juvenile whales to the cause.

The enduring appeal of the “revenge of nature”

Those of us whose hearts break almost daily to witness the ecocidal destruction that capitalism is wreaking on the planet’s animals and ecosystems might be forgiven for saluting these cetacean avengers. They might appear to us like grimly determined cinematic super heroes, gallantly if tragically fighting one last battle to defend their home and their species from annihilation.

Along with the horrific fires on the Pacific coast, such images encourage us to envision the long-overdue “revenge of nature” itself, the moment when some sort of planetary ecological consciousness finally rises up and gives us humans what is coming to us. In the early days of the ongoing pandemic, this narrative was mobilized by no less than Pope Francis to explain how our sinfully ecologically destructive ways created the conditions for a zoomorphic virus like SARS-Cov2.

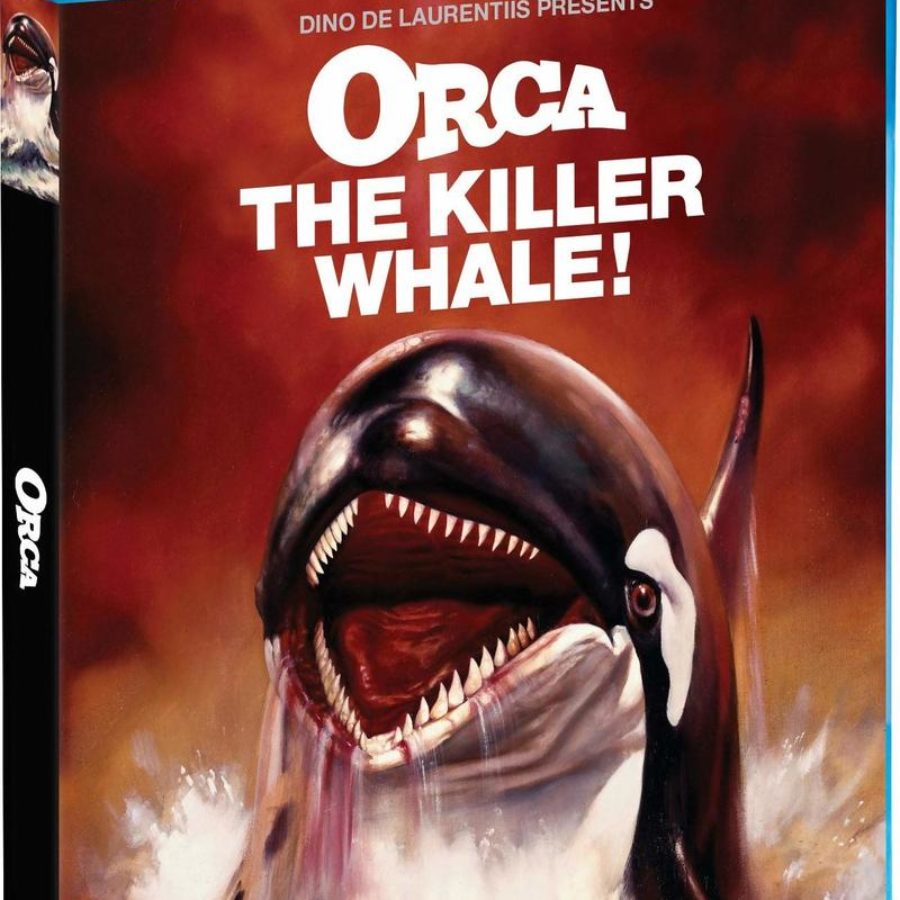

There is a tempting neatness to this narrative, and god knows that, by any measure, what we have done to the planet in the name of “progress” and profit deserves revenge. We have also literally seen this countless times before, from sci-fi cult classics to the subgenre of animal horror — including, notably, the 1977 film Orca — to blockbusters like Jurassic Park or Avatar. Stories about nature’s revenge — or revenge on behalf of nature — are familiar and satisfying. Apropos of whales, the fascinating classic Moby-Dick is ultimately about the revenge of nature in the form of the malicious eponymous white whale.

But for those of us who hope to see the mobilization of humanity towards the end to this system of ecological destruction, the revenge of nature story does not do us good service. Ultimately, it reproduces many of the fundamental ideological mistakes and mystifications that power and justify ecocidal capitalism in the first place.

It is capitalism, not humans

First, much like the charismatic term “the anthropocene,” the “revenge of nature” misidentifies the source of the problem as humanity in general. The real culprit is the particular system of global human and environmental exploitation and disposability: capitalism.

The reality is that we humans have, throughout our diverse history, found many ways of living in dynamic balance with natural forces. For many Indigenous civilizations, for instance the Anishinaabe on whose lands I live today, this relationship with non-humans is a central part of an ethical, political, cultural and spiritual system.

Capitalism is by far the most profoundly destructive of several modern economic systems that have despoiled the earth’s ecosystems. And unlike other systems — for all their many faults — capitalism has proven itself to be completely, disastrously ill-equipped to manifest the kind of coordination that would be necessary to halt ecological destruction. In a nutshell, this system drives each nation, industry and firm to compete with one another to avoid meaningful environmental cooperation and regulation in the name of preserving and accelerating accumulation.

By misidentifying “humanity” as the perpetrator of capitalism’s crimes we trade in cheap misanthropy, imagining that it was somehow our tragic destiny to despoil our home. Not only is this profoundly convenient for the systemic and corporate forces of ecological destruction, it traps us in a kind of self-loathing political stasis.

“Nature” does not exist

Second, the “revenge of nature” story continues to perpetuate the unhelpful idea that humanity and nature are fundamentally opposed. As Jason W. Moore notes, this has long been the fundamental myth that has animated the profound and destructive arrogance of colonial, patriarchal and capitalist worldviews. These were rooted in Christian ideologies that framed humanity as elevated above and separate from nature, endowed with a unique, Godly soul and entitled to make use of “nature” as it saw fit.

Instead of seeing the human animal as one that has always transformed its environment and been transformed by its environment, this dualistic worldview made the abstract notion of “nature” a subordinate but also a threatening force. As Vandana Shiva and Maria Mies observed decades ago, within that ideology, women, non-Europeans, the poor and the disabled were considered closer to nature than the idealized wealthy, educated white man and treated accordingly: objects of pleasure, use and disposal.

If nature can be said to be taking revenge on humanity then, necessarily, nature and humanity are diametrically and fundamentally opposed. As I have argued elsewhere, the powerful always fear the revenge of those whom they oppress. They do so at exactly the same time, and to the same proportion, as they use a kind of needless, warrantless revenge to reproduce and defend their power through policing, repression and punishment. Oppressors project onto the oppressed a capacity and desire for revenge that is the mirror image of the daily, normalized vengeful violence that holds a system of oppression in place.

So it is with the revenge of nature story: we project onto “nature” the kind of ruthless vengeance that is the grim reflection of the vengeance “humanity” has taken on “nature,” and in so doing we reaffirm precisely the myths that enabled this vengeance in the first place.

Human narcissism

This leads to the third problem, revenge of nature narratives narcissistically projects human intentions and behavior onto other animals. This the effect of simplifying what are complex and interwoven ecological phenomena.

Revenge is, as James Baldwin so wisely put it, a “human dream.” It is the name we have given to the particularly human combination of premeditated malice, unanswered injustice and moral outrage. Do other animals take revenge? We do appear to have evidence that some species that we consider intelligent, including other primates and cetaceans, sometimes undertake what appears to us as retributive actions. Many of us have house pets that we would swear take revenge for idle neglect or other petty crimes, throwing up hairballs on the bed or shredding our favorite shoes. But to call this “revenge” is to project onto other animals a complex “human dream” in a way that is inaccurate and often unhelpful.

As in the case of the vindictive Gibraltar orcas, revenge offers us a profoundly simplified explanation for what is, if we are to trust those scientists who have dedicated their lives to the whale’s care and study, much more complicated. We simply do not know why the orcas are acting the way they do, and if we have learned anything about ecosystems and their impacts on animal behavior it is that they are profoundly complex.

As Donna Harawy makes clear, our fate as a species, and the fate of thousands of other species, depends on us humans coming to terms with the complexity of natural systems and their dense, beautiful networks of interreliance, one indicator of which is animal behavior. Simply projecting our own narratives of revenge, cast in the forge of human culture, onto animals as a convenient explanation for how we feel about animals’ behavior is no help at all.

Big nature as conspiracy theory

This leads to the final problem with this revenge of nature story: it creates a kind of supernatural force called “nature” that somehow, in its global totality, with a supernatural intelligence, coordination and intention,“takes revenge.”

Leaving aside some of the more spiritualist takes on the Gaia Hypothesis, there is no credible evidence for such a God-like, all-encompassing entity. Indeed, our attraction to imagining — explicitly or implicitly — that there is such a “big nature” out there, capable of plotting and exacting revenge, is very much like the kinds of anti-scientific conspiracy theories that today haunt the globe. In all cases, some supernatural or all-powerful force is attributed with suprahuman power. Like other conspiracy theories, this notion of nature is profoundly demobilizing.

Why? It would be tempting to imagine that the looming threat of nature’s revenge would scare us humans straight and force us to realize that our ecocidal actions will lead to our doom. But when has this actually worked, outside of fiction and film? This approach makes a fundamental error in its theory of change, assuming that, just as “nature” must have “woken up” and taken up its sword, so too must now humanity come together and change its ways.

But who is this “humanity”? The global supermajority of scientists have been warning “us” for decades about the impacts of our actions and no meaningful action has been taken. Governments, with a handful of exceptions, are so beholden to capitalist forces within their own nations and around the world they have, in spite of some pretty words, squandered those decades.

Humanity as a whole will not “wake up” unless and until it mobilizes and organizes with clarity, intention and intelligence through ungovernable grassroots movements capable of bringing capitalism to its knees.

That goal, however, is ill-served by the “revenge of nature” narrative because it reaffirms one of two demobilizing ideas. First, if nature is to take revenge then why do we humans need to rise up? Will it not take care of the problem for us? Second, perhaps we simply deserve this revenge? Perhaps we are such poisoned and poisonous beasts that we deserve annihilation.

As has been so often said, it has become easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. In a sense we fantasize about some kind of vengeful “nature” as a kind of collective death drive, a lust for obliteration that stems from our unwillingness to overcome some deep contradiction. We yearn for the annihilation we believe we deserve, precisely to excuse ourselves from the hard work of preventing that fate through collective action.

Now you might rightly point out that very few people actually believe in the strong version of this argument, that “nature” is a superhuman intelligence that is actually intentionally taking revenge. You might argue that advocates use this narrative for dramatic purposes to marshal public sympathy, interest and solidarity.

Perhaps so, but my argument remains that this narrative is profoundly unhelpful: it does not meaningfully cultivate sympathy, interest and solidarity, let alone mobilize action or organization. Rather, it reaffirms many of the ideological stories that have led us to this point: the recasting of capitalism’s crimes as humanity’s fate, creating a false distinction between humanity and nature, and projecting onto nature convenient narratives rather than striving for deep understanding.

The “revenge of nature” narrative contributes to a doomscrolling obsession with our own helplessness in the face of the destructive rampage of a capitalist system we have created.

Avenging nature?

The orcas are not taking nature’s revenge. But we can, and we should. We should avenge the destruction of our kindred species and our fellow humans at the hands of capitalism. We should do so by abolishing that system before it can continue its own reckless, relentless revenge.

We have heard all too much about climate grief. What of climate vengeance? As the late, great proletarian troubadour Utah Phillips put it “The earth is not dying, it is being killed, and those who are killing it have names and addresses.” Yet I do not think that isolated acts of revenge against individuals will actually transform things. Capitalism as a system makes every person completely replaceable, even at the top. Yesterday’s CEO and tomorrow’s CEO are the same.

What, however, would it mean to avenge nature? Elsewhere I have suggested that while revenge fantasies — like the “revenge of nature” narrative — are profoundly demobilizing, so too is the almost universal insistence on what I call “reconcilophelia”: our love of just-so stories of forgiveness that substitute the moral transformation of individuals for real systemic change.

An avenging imaginary, by contrast, holds fast to our fury as a grounds for solidarity. A revenge fantasy that dreams we might take the oppressive, coercive and destructive power of capitalism — the masters’ tools — for our own in the name of justice. By contrast, an avenging imaginary recognizes something more profound: we must transform power and develop new forms of life together. We must abolish the systemic sources of ecological violence, not simply its individual agents.

In the case of avenging nature, this can only mean overturning capitalism as a whole, including its profoundly unhelpful ideological infrastructure.