This text, published in English on Mediapart, is a contribution to the Berliner Gazette’s “After Extractivism” text series; its German version is available on Berliner Gazette. You can find more contents on the English-language “After Extractivism” website.

It is difficult to find a more fitting and terrifying insignia than palm oil of the intersection of capitalism’s economy of exploitation and ecological destruction. For nearly 200 years, this plantation commodity’s development has been marked by sacrificial violence where, in the name of profits and cheap prices, human and non-human beings have been placed on the altar of the market.

Today, palm oil is estimated to be present in some form in at least 50% of supermarket products. It is a cheap oil for the frying and fattening of processed baked goods, a base for soaps, detergents, and cosmetics, and a trace ingredient in the surfactants, preservatives, and stabilizing agents that are increasingly part of our diets. It’s also an important source of biofuels, touted as the key to a “green” transition within capitalism.

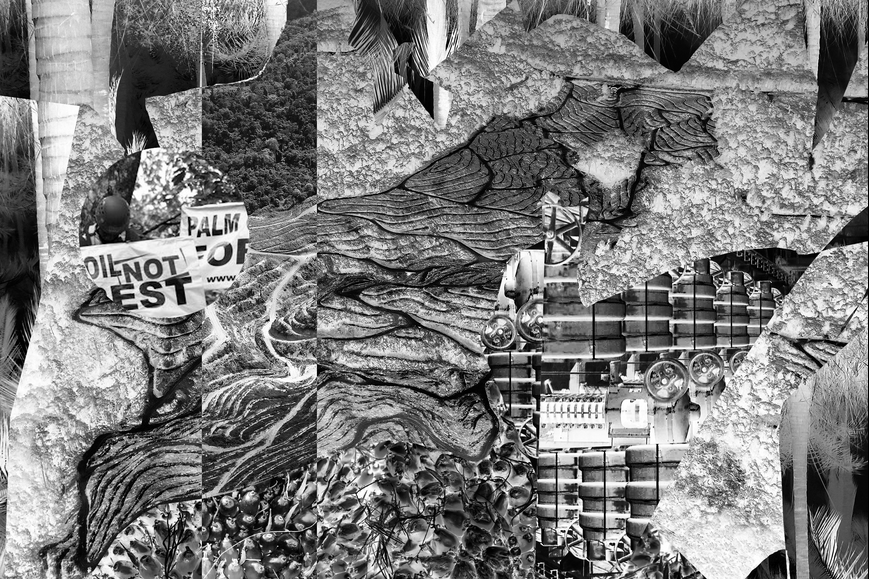

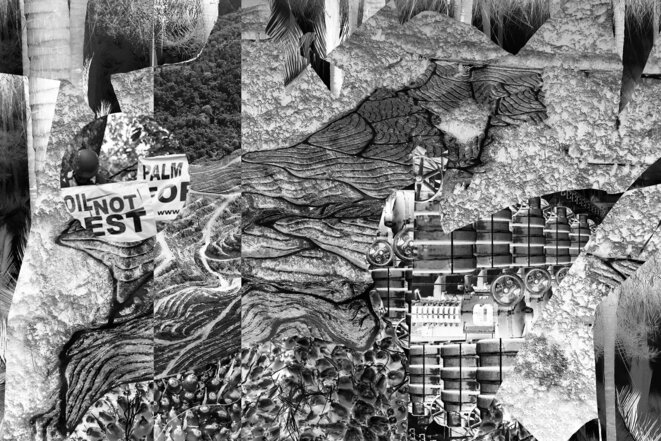

But over the past two decades, environmental and human rights groups have sounded the alarm.

Growing markets for palm oil have led to catastrophic tropical deforestation as biodiverse ecosystems are razed to make way for lucrative monoculture plantations, releasing massive quantities of sequestered carbon. On the ever-expanding palm oil frontier, land-grabbing is rampant. In Indonesia and Malaysia, from whom some 70% of the global palm oil demand is exported, as well as, increasingly, Brazil, Columbia, and Honduras, a handful of extremely powerful companies control the market. In spite of two decades of efforts by a roundtable of these corporations, alongside sympathetic governments and wary non-governmental organizations, towards voluntary regulation and auditing schemes, human rights abuses are rampant, including the intimidation and assassination of union organizers, Indigenous activists, and environmental journalists.

The colonial horror of palm oil

The horrors of the palm oil industry are exhaustively documented and the subject of major campaigns by human rights and environmental groups and many government task forces. But what few of these attend to, and what I want to highlight, is the deeper entanglement of palm oil and extractive capitalism.

The story of palm oil’s emergence as a global commodity has plenty to teach us. The oil palm has been cultivated and harvested for millennia in it’s native West Africa, where its products played a foundational culinary, spiritual, cultural, political, and economic role. When enslaved people and their allies around the world rose up and forced the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in the preeminent British Empire in 1807, Liverpool merchants who had made their fortunes in that horrific economy-defining business searched for new, non-human cargo for their ships. They found in palm oil an abundant commodity to extract from Africa that could, in Europe, be transformed into a cheap grease to lubricate the locomotives and steam engines of the dawning industrial revolution.

The same networks of ecological and economic violence that were used to extract and commodify African people were turned towards exploitation and enslavement within Africa itself to secure artificially cheapened palm oil. Industrial chemists in Europe soon found ways to refine the stuff into candles and soap, two of the first mass commodities, which, ironically, were both sold to European publics using racist imagery that encouraged consumers to identify with the allegedly noble ambitions of empire: to bring commerce, Christianity, and civilization to African people painted as barbaric savages.

To this day, the trope persists.

A history of violence hidden in plain sight

The consumer is led to believe that, in partnership with benevolent “green” corporations, they can do their part for the world simply by buying “sustainable” products. Beyond the falsity of claims to “sustainability,” such discourses reiterate a colonial and white supremacist worldview in which the citizen-consumer in the Global North expresses a self-satisfied benevolence through their capitalist transactions. Both in the 19th century and today, this approach abandons any struggle for global solidarity – which we desperately need – for a kind of consumer narcissism.

It also hides something deeper and more perverse. In the 19th century, as Europe’s predatory states expanded ever-deeper into West Africa and aimed at securing more and more palm oil exports, these incursions were often justified in the name of a humanitarian intervention to “liberate Africans from local kings” whose practices included human sacrifice. Gory details of these practices were salaciously depicted in the British press to build support for imperial invasion. But this was a form of misdirection: the goal was always to build an economy of extractivism.

Further, rendered invisible was the fact that the British Empire itself was a society of human sacrifice: whole civilizations were wiped off the face of the earth in the name of its capitalists’ need for palm oil and other basic materials; even in the British factories where those materials were transformed into commodities, workers, many of them children, were sacrificed to the machines as industrial accidents, overwork or chronic poverty took their toll.

The alleged human-sacrificial customs of the non-white, colonized “other” helped distract and deflect attention from the monstrous sacrificial system of capitalism, hidden in plain sight.

Workers, forests, and the world’s poor

Today, such conditions of extractive capitalist human sacrifice persist in new forms. Of course, we can point to the atrocious working conditions on and around oil palm plantations. From Southeast Asian to West African to Latin America, the abuse and exploitation of migrant workers has been a mainstay of the industry, workers often displaced by previous rounds of extractivism that have forced them or their ancestors from traditional land bases and sustainable economies. In the palm oil fields, migrant workers who are often denied protections are exposed to toxic chemicals, dangerous working conditions, conditions of debt-bondage, and sexual exploitation.

Often, these horrific conditions and the burning of forests are perpetrated not by brand-name consumer products companies or even the corporations that supply them with palm oil but sub-contractors and sub-sub-contractors operating at the frontier where auditors and journalists don’t travel and where government officials can be intimidated and bribed, conveniently allowing those capitalists higher up the supply chain to claim ignorance or helplessness.

But palm oil’s economy of sacrifice is not only one that places workers and the forest on the sacrificial altar. While the industry’s defenders brag that they are reforesting the world with fast-growing plantation plants, the net carbon emissions represent a significant contribution to anthropogenic climate change and the destruction of biodiversity, both of which have profound human impacts especially on the world’s poorest people. Ironically, it is precisely the world’s poorest people who have been transformed by sacrificial extractive capitalism into the main consumers of palm oil: it is, today, the fat of the world’s poor.

Middle-class consumers in the Global North may pride themselves on helping save orangutan habitat by forgoing Nutella or other palm oil-laden foods. But for hundreds of millions of people around the world, imported, refined palm oil is a basic foodstuff, having replaced locally-produced plant and animal fats in their diets thanks to its incredible artificial cheapness. The health impacts are significant, not only because palm oil is high in saturated fats which jeopardize heart health, but because it is found in so many cheap, processed and prepackaged foods that have become the staple or poor people’s diets, especially of those poor people who have been displaced from land bases where they can produce their own food.

Feeding surplus populations with palm oil

One demonstrative example is the diet fed to prisoners in the American system of mass incarceration, which disproportionately imprisons working class Black and racialized people. Here, almost every item of a standard prepackaged meal (bread, processed cheese, processed meat, packaged cookie, sugary drink-mix) is heavy in cheap palm oil. Indeed, in the US prison system the prepackaged ramen instant noodle (basically: wheat flour, palm oil, and sodium) has become a significant alternative currency among imprisoned people who, without it, are often denied enough calories to survive.

In her landmark 2007 book “Golden Gulag” geographer and prison abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore takes such prison environments as indicative of a broader shift within capitalism towards what she, instructively, calls an “era of human sacrifice.” Her book focuses on the prison as a capitalist technology for the management of “surplus populations,” people who have been made dependent on wages within a capitalist economy to purchase the necessities of life, but for whom capitalism increasingly has no waged work, forcing them to accept extractive forms of exploitation or survive in the “informal economy.”

Claims that this “surplus population” is due simply to automation – suggesting that capitalist industries require fewer workers – are largely bogus and ahistorical: the reality is that capitalism has always generated large populations of would-be workers that represent two things: a “reserve army” of unemployed people to help depress wages in the broader economy and a hyper-exploitable population on whose backs the broader economy is built. Today, palm oil is chief among the “cheapened” foods that sustains the life of these and other sacrificial victims of the extractive capitalist economy.

Against and beyond the system of human sacrifice

As was the case with the British Empire, today’s global form of extractive capitalism is a system of human sacrifice hidden in plain sight. I am attracted to this term not simply for dramatic effect. Surely, the horrors of the global economy don’t need to be the subject of hyperbole: they’re bad enough on their own. Rather, thinking about human sacrifice invites us to consider the cosmological dimensions of this economic violence. In the name of a god-like “market” we, today, legitimate extreme forms of human and non-human sacrifice and suffering. The high priests of this god insist that, to question or interfere in the will of the market will bring chaos and calamity. But do not the high priests and beneficiaries of all sacrificial societies claim something similar? Were they not to place the victim on the altar and cut out their heart, the gods would starve or be angered and unleash terrible violence on everyone.

Deeper still, framing extractive capitalism as a system of human sacrifice helps us understand the magnitude of the task before us to achieve some horizon after extractivism. Our task will not simply be to abolish the old economy and install a new one. It must necessarily include a radical transformation of belief, of value, and of meaning-making. At stake is the creation or rekindling of other modes of post-capitalist interdependence.

We are already in an interdependent world, but that interdependence is encrypted and managed by capital, a force that is driven by competition and profit compulsion, and that has been exhausting people and the planet in the name of its own reproduction. The past two centuries of palm oil’s history show us how deeply enmeshed we all our, materially and culturally, with an order of capitalism that, today for example, manages to sustain itself by promoting ever more “green consumerism.” Here, the subjecthood of the capitalist consumer is revamped as a solution, even though it is a leading contributor to the problem.

To overcome this system and to pave the way for a transition into a just world, then, requires we not only transform the palm oil industry, not only transform the global food system, but transform ourselves and our communities on a fundamental level. Here, we must dare to dream dangerously of global commoning and global forms of socialism, and new ways of configuring the dynamic triangle between the individual, the collective, and the public.