Citation

Haiven, Max. 2017. “The Uses of Financial Literacy: Financialization, the Radical Imagination, and the Unpayable Debts of Settler-Colonialism.” Cultural Politics 13 (3): 348–69. https://doi.org/10.1215/17432197-4211350

Abstract

This article is a contribution to critiques of the mainstream trends in financial literacy education and argues that they typically produce a profound financial illiteracy by obfuscating the systemic and structural dimensions of debt, financial hardship, and the patterns of financialization, thus reaffirming a neoliberal trend to privatize social problems. I explore how this financial illiteracy dovetails with the production of “white ignorance” and the erasure of the racialized injustices of contemporary global capitalism. While the case study of financial literacy educational materials targeting Indigenous people in Canada largely confirms this approach, it also gives us clues as to what another, better financial literacy might look like. The article concludes by asking what financial literacy education for the radical imagination might look like and what the further decolonization of that education might imply. It ends with a celebration of settler-colonial bankruptcy as a moral and political-economic opening for a radical way forward.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1tp-hz-ePC_UCsCvF1TbX-E8f–oK_Y4e

The Uses of Financial Literacy: Financialization, the Radical Imagination, and the Unpayable Debts of Settler-Colonialism

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath of austerity, financial literacy education has been widely propounded around the world as a remedy for rising personal debt levels (Arthur 2012, 2014; Alsemgeest 2015; Xu and Zia 2012). Yet the enthusiasm for such education, which usually [End Page 348] takes the form of workshops, pamphlets and other materials, and school curricula, is misplaced. There is inconclusive evidence to suggest that financial literacy education actually produces significant and consistent economic results in people’s lives (see Alsemgeest 2015; Bruhn, Ibarra, and McKenzie 2013; Willis 2008, 2011). More broadly, financial literacy education tends to reinforce and reify conventional, neoliberal approaches, attitudes, and ideologies toward debt, credit, finance, and money (Arthur 2012; Martin 2002, 2015). Generally speaking, most such materials and approaches posit debt and financial hardship as individual responsibilities that can be overcome by education, planning, and perseverance. In this sense, they fundamentally obscure the systemic, structural, and social factors that shape personal financial experiences under neoliberal global capitalism, especially as those factors intersect systems of oppression and exploitation, including those based on race, gender, class, and colonial history.

In this article I draw on Richard Hoggart’s groundbreaking book The Uses of Literacy ([1957] 2009) to argue that the conventional approach to financial literacy education typically also produces a profound neoliberal financial illiteracy. Yet the problematic enthusiasm for financial literacy education and the expansion of financial literacy education into a wide variety of institutions and social spaces also offers opportunities for critical interventions. I take up the case study of a financial literacy booklet targeted at financially precarious Indigenous people in the Canadian province of British Columbia, which exhibits most of the hallmarks of typical financial literacy materials and normalizes, individualizes, and renders invisible the effects of the intertwined system of capitalist neoliberalism and present-day settler colonialism that is, in fact, at the root of the audience’s financial precarity. But, I argue, this booklet also opens the door for an anticolonial reading. From this I draw out the question of what a financial literacy that awakened, rather than deadened, the radical imagination would look like. Here, the radical imagination is the power to collectively envision and manifest different social and economic orders. I conclude that such a process would necessarily also need to be anticolonial and aimed fundamentally at allowing us to imagine anew the relations of social and economic value from their roots. Indeed, I argue it would need to account for the ruinous debts incurred by and that continue to define settler colonialism.

This investigation is important because financial literacy education is one of the key means by which the financialized, neoliberal order is normalized and legitimated and by which the forms of structural and systemic power bound up in it—based on colonialism, race, class, gender, and other vectors of oppression and exploitation—are erased from the political, economic, and social imagination. As I have elsewhere argued at length (Haiven 2014a), the interwoven economic and cultural processes identified as financialization are reproduced in significant part by conscripting a wide variety of social subjects by appearing and promising to empower and elevate them, all the while intensifying inequalities and systemic injustices. Discourses of financial literacy dovetail with neoliberal reconfigurations of social welfare programs and international aid schemes based on the idea that free markets that harness and encourage personal entrepreneurship are the solution to all manner of social problems (Joseph 2014; Roy 2012). Yet [End Page 349] cultural activists need to be attentive to the rare but crucial opportunities such schemes open up, and students of cultural politics must work to identify and seize such opportunities for a more profound and transformative education that aims to build a more substantial literacy of finance and the radical imagination (see Giroux 2004).

Financialization

In recent years, the term financialization has become so widely and diversely used that, like the terms globalization and neoliberalism, it has lost much of its critical and analytic edge. Yet the phenomena that financialization seeks to describe are real. Financialization refers to (a) profound expansion of the magnitude of wealth and economic power wielded by the so-called FIRE (finance, insurance, and real estate) sector; (b) the way this wealth and power influences and reshapes the operations, logics, motivations, cultures, and processes of firms, social and public institutions, and diverse individuals well beyond the confines of that sector; and (c) the broader economic, political, social, and cultural transformations these portend.

Economically speaking, financialization denotes the increased power, volume, and influence of the FIRE sectors (Lapavitsas 2013). Broadly speaking, it names a moment when the annual volume of abstract financial exchanges traversing interconnected digital global markets vastly dwarfs the planet’s gross domestic product, a moment when even mighty transnational corporations are brought to heel by the superego-like pressures of “the markets” (LiPuma and Lee 2004; Bryan and Rafferty 2006). Financialization also speaks to the reorientation of the priorities, organization, and management of all manner of firms toward the production of financial wealth and the extreme disciplinary power of financial markets on all manner of capitalist actors (Lapavitsas 2013).

But it’s not only corporations: as neo-liberal policies have fundamentally transformed governments into highly indebted servants of corporate profit under the sway of financial markets, national debts (Bello 2013; Soederberg 2014), currencies, and fortunes are traded and speculated upon at ever increasing velocities and with ever more disastrous volatility (Harvey 2010). Meanwhile, the upper echelons of governments and supranational bodies of the world are often staffed with the alumni or friends of powerful investment banks, the same institutions to which those governments must turn to facilitate their basic financing (Bello 2013; Levitt 2013).

Yet it is all too easy and tempting to limit our understanding of financialization to the realm of shadowy elites. In reality, the same neoliberal policies that have hamstrung governments have, as Ulrich Beck (2009), among others, has noted, also shifted the burden of social risk onto the individual as the social safety net and welfare state have been eroded (Hacker 2006). As health, education, and housing cease to be seen as public goods but, rather, as private investments, individuals are encouraged to go further and further into debt and embrace a personal ethos of speculation (see McClanahan 2016; Ross 2014). As Randy Martin (2002) notes, financialization represents the “reconfiguration of social affiliations” aimed at transforming each of us into savvy risk managers who see nearly all aspects of our lives as opportunities for potential leverage, speculation, and investment. Education, housing, work—all have become opportunities for us to improve and leverage our human capital and accumulated assets in the name of economic survival. [End Page 350]

Indeed, Martin (2007) has provocatively but perceptively noted that today the world is divided not so much into the haves and the have-nots as into the lauded risk takers and the abject “at risk.” While the former are lionized for their independence from the state and their embrace of the opportunities granted by our global market-driven society, the latter become the targets of biopolitical surveillance and scrutiny (see Roy 2012). It is by no means an accident that the line between the risk takers and those at risk closely tracks what W. E. B. DuBois called the color line, traversing historical and contemporary patterns of oppression, exploitation, and dispossession but now in ways that blame the victims for their failure to seize their potential (see Chakravartty and da Silva 2012; Joseph 2014; Wyly 2010). Thus, in addition to the transformation of economics, politics, and society, financialization ultimately represents a shift in social meaning-making and cultural values (Allon 2010; La Berge 2015; McClanahan 2016).

In sum, Martin (2007) argues that financialization represents a reorientation of capitalism toward futurity. On the one hand, through instruments like the derivative contract, financialized capitalism aims to transform future potentials into present-day commodities, transforming the world into a spectrum of risks to be speculated upon. But in so doing it affects and predetermines future outcomes by shaping present-day realities. On the other hand, as I have argued (Haiven 2014a), financialization both demands and depends on a profound recalibration of the imagination, “empowering” us as individuals and collectivities (e.g., families, communities, nations) to recast our hopes and dreams for the future in financial terms. The result is, as Mark Fisher (2009) suggests, a kind of nihilistic capitalist realism that normalizes oppressions, exploitations, and injustices of a financialized society as inevitable and renders them personal, rather than social, problems to be repaired, ironically, through further financialization.

Financial Illiteracy in an Age of Racialized Foreclosure

As Christian Marazzi (2010) notes, we cannot rightly view the incredible wealth and power of the financial world today without also taking in that it rests on the proliferation and manipulation of multiple layers of debt: government debt, credit card debt, student debt, even strange, arcane forms of debt we would likely never imagine, like the lucrative debt industry that finances the expansion of fast-food franchises, or the secretive industry of corporate debt insurance and reinsurance that makes the world of finance go’round (see also Lazzarato 2012). The success of the FIRE industry is in many ways an index of the explosion of debt in the neoliberal period when tax cuts and deregulation have led governments to borrow deeply from the markets and pass down the costs of social care such as health, education, housing, and income security to individual citizens (Ross 2014). These are, as mentioned, citizens who have not seen their real wages (adjusted for inflation) increase since the 1980s and often depend on credit to finance increasingly precarious lives, where part-time, temporary, casual, and intermittent work are the norm (Ross 2014). The financialized destruction of the welfare state and the rise of precarious labor tend to most deeply affect those who also struggle under the burden of oppression based on race, gender, and other markers of difference (see Joseph 2014; Taylor 2016).

The US subprime mortgage scandal that triggered the 2008 financial crisis [End Page 351] showed us conclusively that the world of high finance is deeply and tragically invested in and manipulating the fabric of everyday indebtedness (see Aalbers 2012). The ensuing crisis should have also alerted us to two other factors. First, this everyday indebtedness is itself reliant on a massive cultural transformation that normalized the financialization of housing—houses now represent not only a shelter but a privatized technology of economic survival and financial speculation in a neoliberal moment when no form of state or social care can be relied upon (see Harvey 2012). Second, finance, debt, and credit always imply race and the histories of racism that led, for instance, to predatory loans being extended largely to Black homeowners, and a subsequent wave of foreclosures that disproportionately targeted and evicted Black and Latinx people and destroyed the fabric of their neighborhoods (Chakravartty and da Silva 2012; Dymski 2009; Wyly et al. 2012).

In a fashion that appears largely oblivious if not insouciant to all these systemic and structural factors, conventional financial literacy education has vastly expanded in the past decade (see Arthur 2012). Briefly, financial literacy education names an expanding field of activities geared toward offering primarily “at-risk” populations access to financial skills and knowledge they are deemed to lack (Arthur 2014). Such initiatives include websites, pamphlets, weekend classes, high school teaching modules, and online games. These typically focus on such topics as how to draw up and keep to a budget, how to identify and balance different forms of debt and credit, how to engage and negotiate with financial institutions, how to set realistic financial goals, and how to prepare and file tax returns (Arthur 2012; Xu and Zia 2012). Such efforts dovetail with a shift in global development discourse from financial “aid” to financial “inclusion,” including philanthropically driven programs aimed at encouraging capitalist market penetration as a means to alleviate poverty and improve social indicators (see Bateman 2010; Roy 2010; Soederberg 2013)

On the surface, there is nothing outwardly objectionable about such initiatives: in a world dominated by debt and finance capital, the capacities they aim to cultivate have indeed become basic survival skills. However, both the form and content of financial literacy initiatives, as well as the broader enthusiasm for them among corporations, policy makers, and educators, are symptomatic of the overarching system of neoliberal financialized capitalism that seeks to privatize and individualize what are, in fact, collective and systemic problems. Yet that system and its effects are ignored, obfuscated, or occluded in almost all financial literacy texts and programs, leading, I am suggesting, to a profound financial illiteracy on both an individual and systemic level.

This is all the more pronounced in an allegedly postracial moment, when the myths of a “level playing field” of free markets and the formal legal equality of citizens are frequently cited as evidence that racism is merely the pathological atavism of despicable individuals and that society as a whole is “color-blind” and successfully multicultural (Bonilla-Silva 2014; Goldberg 2011). We might hope that these myths would have been discredited when illuminated by the evidence of the spate of police murders of Black people in the United States (see Taylor 2016), the extremely disproportionate number of Indigenous people incarcerated in Canada (Macdonald 2016), or any number of other systemic racist realities that relentless social movement agitation [End Page 352] in the last decades has revealed and challenged.

Yet racial illiteracy and financial illiteracy work hand in glove. Racial illiteracy here might be understood as the silent pedagogy of what Charles Mills (2007) calls the epistemology of white ignorance, one that teaches a certain systematic forgetting and reinforces the presumption of equality where (often deadly) inequity persists in spite of formal legal equality (see also Giroux 2012). Indeed, the seemingly self-evident racism exhibited in the campaigns for and by the supporters of right-wing backlash politics on both sides of the North Atlantic couches itself still in a postracial rhetoric that insists that so much has been done to accommodate and ameliorate systemic and structural racism that the tables have turned, that now those who enjoy the racial privilege of whiteness are the victims (see Goldberg 2011; Mackey 2016; Taylor 2016).

The illiteracy that I am arguing is produced by most conventional and formal financial literacy education projects dovetails with this informal racial illiteracy because both offer an extremely narrow (indeed solipsistic) vision of the world that focuses exclusively on the highly constrained actions of the individual. Yet the worldview it produces encourages the individual to imagine, against so much (erased) evidence to the contrary, that personal behavior can allow one to avoid or rise above systemic and structural constraints. The presumed value of conventional financial literacy education is based on a cruel optimism (Berlant 2011) that presumes that educated individuals and their families can master their economic reality through hard work, careful planning, and frugality. In this sense, financial literacy education is a form of what Henry Giroux (2004) calls “public pedagogy,” but one that actually inculcates a profound racial illiteracy, normalizing the notion that individuals of any racial group have only themselves to blame for their successes or failures. In both cases, the structural, systemic, and historical dimensions of exploitation, oppression, inequality, and discrimination are bracketed out (see also Giroux and Searls Giroux 2004).

The Abuses of Literacy

Such a production of an illiteracy in the name of producing literacy has a long if sordid pedigree. The fact that many Indigenous peoples did not use alphabetic letters in their communications (see Paul 2006) was taken by colonizers as evidence of a cultural and intellectual inferiority, licensing them to inflict brutal domination in the name of paternalistic “care” (see Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015; Razack 2015). Frantz Fanon (2008) and other anticolonial writers early on noted that the colonialist obsession with providing literacy programs to people they believed to be benighted illiterates was a key method of control and humiliation, aimed precisely at erasing the forms of Indigenous cultural knowledge and practice that might be the source of an insurgent resistance and challenge Eurocentric narratives of cultural supremacy (see Cote-Meek 2014; Freire 2000). Illiteracy rates could always be pointed to as evidence that the Indigenous population was not yet ready to manage its own affairs. The cant of literacy places on Indigenous individuals the responsibility to overcome the confines of their colonial subjecthoods while erasing or normalizing the violence of colonial subjugation. And literacy has always been key to producing a comprador class of Indigenous intelligentsia and functionaries capable of mediating between colonizer and colonized (see Ashcroft, Griffith, and Tiffin 2002). [End Page 353]

Within the context of settler-colonial states like Canada or the United States (see Coulthard 2014; Dunbar-Ortiz 2015; Moreton-Robinson 2015; Smith 2005; Veracini 2010; Wolfe 2016), the alleged illiteracy of Indigenous peoples relative to colonial written languages fundamentally delimits the understanding of what a broader concept of literacy might. The narrow notion we inherit masks how woefully illiterate colonists themselves were when it came to other media and modalities of communication (see, e.g., Simpson 2014). For instance, the beligerent inability of Dutch and British traders, colonists, and administrators to be able to fully “read” the wampum belts that enshrined the text of the international treaties to which they were signatories or subjects, a useful illiteracy, allowed them to conveniently ignore the protocols and agreements that governed the relational management of the land (Asch 2014; Gehl 2014; Kelsey 2014). Settlers’ illiteracy in terms of what Trudy Sable and Bernard Francis (2012) have called the “language of the land” enabled them to blithely despoil, abuse, and exploit that land and its nonhuman inhabitants for their profit, as it does to this day (Armstrong 2007). And settler illiteracy toward the power of oral history and storytelling and their obsession with the written text represented (and represents), from a certain perspective, a depraved cultural immaturity based on a dangerous intolerance for the forms of generative polyvalence, play, openness, relationality, autonomy, and recursivity that animate Indigenous oral traditions and also political culture (see Sium and Ritskes 2013; King 2003).

Here Richard Hoggart’s influential 1957 book The Uses of Literacy is instructive. Written under the more fitting working title The Abuses of Literacy, this auto-ethnographic book about working-class life and popular culture in postwar England helped set the scene for the emergence of the field of cultural studies. Hoggart focuses on a particularly instructive moment in the 1950s when, on the one hand, thanks to public education programs the British working class had achieved unprecedented rates of formal literacy and, on the other, television had not yet dominated the field of working-class entertainment; thus, novels, newspapers, and magazines were the key cultural signposts for a postwar generation in transition. Hoggart sought to demolish the mythology of the day (still all too active in our own times) that following WWII there had been a “bloodless revolution” that had eclipsed social class as a structuring factor of one’s social, economic, and political participation. He challenged this myth not by presenting convincing statistics to the contrary but instead by—in often quite moving detail—mapping out the rich, full life of working-class communities, the social norms, forms of solidarity and conflict, and political dispositions common to a distinct social and economic class.

Yet Hoggart’s central concern was about the rise of a commercial mass print media that was at once appropriating, mimicking, mocking, and destroying this working-class culture. Of course, Hoggart was not against literacy per se. For Hoggart, himself an academic outsider from a working-class family, popular magazines and novels of the day (almost all of which were owned by ruling-class-owned media conglomerates) made a business model of appropriating the working-class cultural vernacular and sensibility, distilling it into a commercial product suffused with sensationalism, moralism, sentimentality, and reactionary populism, and stripping it of grace, creativity, intelligence, or class antagonism. In this sense, literacy, far from [End Page 354] being an enlightening and uplifting force, had been press-ganged into the service of class interests, conscripting the working classes to a more conformist and conservative culture that, as Hoggart rightly feared, would eventually give rise to neoliberalism and the likes of Margaret Thatcher (see Giroux 2008; Harvey 2005).

The Uses of Financial Literacy

Hoggart’s approach is instructive for analyzing the virtues and vices of efforts toward financial literacy education today. Legal scholar Lauren Willis (2008, 2011), among others, has called into question the financial literacy education modules that were so enthusiastically developed in the first decade of the twenty-first century. She charges that such efforts do not actually provide poor or at-risk learners with adequate skills to meet the daunting challenges they faced in their lives (see also Alsemgeest 2015; Arthur 2014). While few of us today could argue with the personal usefulness of learning how to make and keep to a budget, or how to judge which types of debt are preferable, this knowledge is not particularly useful to those working multiple minimum-wage part-time jobs who still can’t afford the basic necessities of life, a condition that disproportionately affects racialized and Indigenous people in the United States and Canada (see Taylor 2016; Dunbar-Ortiz 2015).

In what can only be described as the height of irony, firms like Walmart and McDonald’s charitably developed their own financial literacy programs for their horrifically underpaid employees (Olen 2013; FinancialCorps 2013). As Willis (2011) notes, often those penning, bankrolling, or distributing financial literacy initiatives or materials are the same companies that make their money from people’s financial illiteracy: payday loan and pawn shops, check-cashing outlets, low-end financial institutions, and retail businesses dependent on ever increasing rates of debt-driven consumer spending.

As Chris Arthur (2014) has argued, financial literacy is dedicated less to actually providing people with useful skills and more to developing and promoting a particular subjectivity appropriate to the culture of financialization (Haiven 2014a). These are subjects who see themselves as miniaturized versions of the financier and see all their personal wealth, capacities, and relationships as assets to be leveraged. Following Maurizio Lazzarato’s (2012) interpretation of Foucault, Arthur notes that financial literacy campaigns by and large encourage and guide us to perform a “work of the self” that inculcates a neoliberal orientation to biopolitical entrepreneurship, where one is tasked with managing one’s life as a savvy risk taker and empowered, individualistic economic agent. As I have argued (2014a), financialization works not because it feels like an inescapable dystopian nightmare but because it offers us a set of metaphors, narratives, tools, and measurements that feel empowering and enlivening. We might suggest that, from one angle, financialization represents a form of storytelling about ourselves and the world we inhabit that makes certain forms of highly delimited freedom possible.

First Nations Financial Fitness

Let us turn to a case study. In 2011 the Aboriginal Financial Officers Association of British Columbia issued a fifty-six-page booklet titled First Nations Financial Fitness: Your Guide to Getting Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise. Targeting Indigenous people in the province, the booklet was funded by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern [End Page 355] Development Canada and overseen by a board made up of representatives of Aboriginal Affairs, the Vancity Credit Union, the Public Guardian and Trustee of British Columbia, the First Nations Technology Council, and the Aboriginal Financial Officers Association of British Columbia.

I have selected this example because I find it to be a salutary example of racially and colonially inflected financial literacy educational materials. However, my desire here is to find not only a demonstrative example but also one that holds the potential for contrary readings. Precisely because this text seeks to intervene in the charged field between race, colonialism, and financialization it is defined by the contradictions therein. As such, it offers a useful text in that it both resonates with and demonstrates the broader trends under critique and offers avenues beyond them.

More broadly, I have selected this text because it hovers over a set of intersectional historical injustices that have been central to the making and remaking of the world capitalist system. As numerous thinkers make clear (Coulthard 2014; Dunbar-Ortiz 2015; Moreton-Robinson 2015; Smith 2005; Veracini 2010; Wolfe 2016), settler colonialism, as a distinct system of power, is the crucible of other systems of domination, including capitalism, white-supremacist patriarchy, and ecological pillage. As a settler on Indigenous lands claimed by the sovereign state of Canada, I feel that these matters have particular importance for the cultural politics that define my body, relationships, and intellectual energies (see Lowman and Barker 2015). But readers farther afield also dwell in a world and a global economy defined by settler colonialism. And more generally, the following example helps elucidate some of the ways financialization advances through and helps reinforce other systems of power that, in our concern for the field of the economic, we all too often bypass—notably, race and imperialism.

The First Nations Financial Fitness booklet is written in plain, accessible, if somewhat clinical, language. It generally mirrors the format, content, and approach of the vast majority of financial literacy materials I’ve surveyed. Chapters focus on how to understand and manage cash flow, common “money traps” like high-interest payday lenders, how to draw up a budget and keep to it, managing banking and credit cards, and the basics of filing one’s taxes. Financial literacy materials typically follow similar formulas and are often accompanied by fictional examples, fill-in-the-blank sections, suggested games or conversations, and other interactive materials.

But this booklet also includes tailored content that aims to speak to a generic working-class or poor Indigenous audience. For instance, sample budgets include lines for bingo, casino, and poker expenses, as well as cigarettes and various forms of income assistance. Much of the booklet focuses on financial “fitness” as a family affair, even providing games and discussion prompts to help families have difficult conversations.

For all that these choices represent implicit assumptions based on stereotypes, it is clear that this publication is also based on both careful market research and the good intentions of well-meaning people, many of them Indigenous. It is not my objective here to level a critique of the motivations of its authors. It is clear from the approach taken here that they are clearly worried about the continued financial exploitation of Indigenous people within a colonial system. While statistics [End Page 356] are difficult to find, one study found that, in the community of Prince George, British Columbia, where 11 percent of the population self-identify as Aboriginal, 60 percent of users of fringe finance institutions (payday loans, pawn shops, check-cashing shops) so identify (Bowles, Dempsy, and Shaw 2011; see also Buckland, McKay, and Reimer 2016). It is, of course, preferable for all people to have the knowledge and means to protect themselves as best they can from the vicissitudes of an increasingly uncaring and economically violent neoliberal system, especially those racialized and Indigenous people who are disproportionately targeted by this violence.

But in spite of the good intentions of their issuers texts such as these emerge from and contribute to a moment of financialization that creates different “subjects of risk” (Roy 2012) from different populations based on historical and contemporary patterns of oppression and exploitation. Such texts typically also work, inadvertently, to erase and normalize the causes of these inequalities and in this way produce illiteracy in the name of literacy. To see such a text as symptomatic of these trends is not to discount its value in the particularities of the present moment. It is, rather, following a method offered by Fred-ric Jameson (1981; see also Tally 2014), to ask these texts, born of and for a sublimely complicated capitalist totality, for the seeds of their own overcoming, the ways they may point toward other horizons than their authors or funders strictly intended. In this particular text, we might point to two such moments.

The first is the central metaphorical move to substitute “financial fitness” for financial literacy. We can only guess at the motivations of the authors, but it may have something to do with the legacies of the infamous residential schools and even contemporary schooling practices that fundamentally devalue and punish Indigenous oral traditions and cast the Indigenous subject and Indigenous knowledge as fundamentally inferior, in need of white colonial tutelage to become literate in white colonial cultural texts and norms (see Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015). Whatever the case, the switch to financial fitness recalls Lazzarato’s (2012) observation, following Foucault, that the management of debt and credit in a financialized age has become a work-of-the-self, a form of ongoing, self-reflexive self-discipline that, though it is required by the overarching social and economic conditions of neoliberal life, promises mastery as a form of freedom, liberation, strength, and vitality.

Perhaps the shift toward the metaphor of fitness was to align with the much larger and widespread efforts by government, nongovernmental organizations, and community initiatives to combat elevated rates of poverty-induced obesity, diabetes, and other illnesses in Indigenous communities and thus perhaps access the problematic Canadian government obsession with reconciliation and healing (see Coulthard 2014). But like that enthusiasm, financial literacy efforts do very little to link these ailments to a longer history of colonialism that has—since even before the distribution of smallpox-laden blankets to Indigenous people as a weapon of war or the forced sterilization of Indigenous women—been biopolitical in nature (see Dunbar-Ortiz 2015; Smith 2005). Indeed, as Sarah Blacker (2014) has argued, many of the educational materials geared toward promoting Indigenous health and fitness themselves echo the rhetoric and cultural codes of financialization, proposing that the body be viewed as a site of individualized personal investment and that exercise [End Page 357] and healthy diets be measured and seen as a form of disciplinary accountability aimed at maximizing personal gain and minimizing personal risk.

Yet in the First Nations Financial Fitness booklet’s favor we might observe that, unlike literacy, which may strike us as an achievable plateau once one appropriates the necessary skills and knowledge, fitness implies a lifelong, reflexive process. Such a framing would to some extent challenge the normative assumption that one can, at some point, be literate enough, and that financial success can be achieved by learning and playing by the neoliberal rules. Using the term fitness rather than literacy generates a covert (if perhaps unintentional) deconstruction of this mythology: as Paula Chakravartty and Denise Ferreira da Silva (2012) have argued, the global financial system fundamentally depends and has always depended upon creating within it sabotaged financial subjects by drawing on and reinscribing the legacies of racism and colonialism. The recurring plunder of Black financial subjects in the United States is only the most evident example: from enslavement to a false “reconstruction” based on debt peonage and sharecropping; the financial disenfranchisement of Black independent farmers in the nineteenth century; and the repeated exploitation of Black renters and homeowners in the twentieth century, not to mention the systematic and incidental exclusion of Black people from access to debt, credit, and mortgages—the list goes on and on (see Coates 2014). More generally, as Chakravartty and da Silva (2012) note, more often than not, the investment that is for the white subject a site of hope and liberation becomes for the nonwhite subject an often deadly trap. The notion of financial literacy might be framed as a normatively white form of storytelling, where investment and financial risk management are rewarded by security, comfort, and success within an overarching color-blind neoliberal system. Financial fitness, instead, implies that even if one becomes fit, one might still be called to run, or fight, for one’s life.

What stands out above all in the booklet is its introduction, which provides a unique framing that then largely disappears from the rest of the text. While it begins with the typical incantation of austerity, “this handbook is a tool to help you help yourself,” it goes on to drop this second-person imperative in favor of the first-person plural to note how important it is to “acknowledge the past and understand the present situation so we can move forward to creating our future.” The notion of financial fitness as a collective problem and responsibility that connects the past to the future is extremely rare in financial literacy materials, which typically inscribe the reader as a socially and temporally isolated agent.

More profound still, the booklet’s introduction insists that

it’s important to note that pre-contact Aboriginal people were a strong and vibrant self-sustaining people. We lived off the land in harmony with nature and with one another. We had assets and items for trade, and we had strong values that guided how we used our assets and how we traded with others. … Our wealth was measured in our ability to manage and sustain our resources. We demonstrated our wealth through caring and sharing with others. The potlatch system [practices of wealth redistribution through gift giving] is an example of financial literacy in a pre-contact context … and it worked—we did not have the poverty and dependency we have today. … In 1884, the potlatch system was banned and so were our teachings about wealth management. [End Page 358]

(Aboriginal Financial Officers Association of British Columbia 2011: 6)

The booklet goes on to propose that, “just like our ancestors, we have the ability to be wealthy. We can access supports and services to learn how to make our money work for us instead of us working for our money. When we have the skills, knowledge, and confidence to make smart decisions about our money, we can achieve our financial goals” (6). These final platitudes undermine the radical nature of the foregoing statements, but those statements are vitally important because they might help reframe the question of financial literacy from a generative anticolonial perspective. If we imagine preinvasion land-based Indigenous economic practices as undergirded by alternative forms of financial literacy and locate the present economic constraints and challenges faced by Indigenous people as the result of colonial policies like the banning of the potlatch, a different form of financial literacy might emerge, one rooted not in the uncritical acceptance of financialization but in the radical imagination.

The Radical Imagination

The preceding section examines how colonial ideologies and discourses were reinforced and challenged in financial literacy texts targeting Indigenous people. I have undertaken such an analysis not in the name of improving Indigenous financial literacy education or making any suggestions regarding alternatives: as a settler subject in Canada, I don’t believe that is my place. Rather, I wish to ask what we, as settlers (and those who, more broadly, benefit from settler colonialism), can learn from the foregoing discussion as it relates to the radical transformation of settler culture, society, economics, and politics. How Indigenous people organize and strategize to survive and rebel against colonialist neoliberal extractive capitalism is vitally important, but not my jurisdiction (see Lowman and Barker 2015). I am interested in how settlers, the beneficiaries of colonialist neoliberal extractive capitalism (to different extents, based on class, race, gender, and other forms of oppression; see, e.g., Day 2016), can better rebel from within, in part by learning from (and taking risky action in solidarity with) Indigenous struggles. For me, the notion of the radical imagination is crucial.

The radical imagination in this sense implies the ability to recognize that the present social order is neither inevitable nor necessary; there have been, there are, and there could yet be other modes for organizing social life (see Graeber 2007). Here, the example of Indigenous social, political, and economic systems in the past and in the present can be vital, though we are wise to recognize that gazing at them can also invite the colonial maneuver of romanticization and appropriation.

The radical imagination is not a normative category and does not map neatly onto any one ideological, political, or identitarian approach. Rather, as Cornelius Castoriadis (1997a) argues, the radical imagination is a constant force of disruption, questioning, and creativity working at the very core of the individual and of society. Castoriadis (1997b) posed the radical imagination as the elemental protean substance of the human subject, but also of social institutions writ large. The institutions of marriage, the police, and the education system, all social power formations, even when concretely or brutally material, are held in place and reproduced through the imaginative work of social actors. Castoriadis likens it to magma, a substance that is [End Page 359] at times fluid but at other times solidifies, only to become liquid again at the next tectonic eruption.

Following Castoriadis, Alex Khasnabish and I have approached the radical imagination not as a private possession located in the mind of the individual but as a collective process that emerges from dialogue, debate, and peoples’ often fraught and difficult solidarity in the face of social power relations (Haiven and Khasnabish 2014). From Robin D. G. Kelley’s (2002) study of the traditions of the Black radical imagination we have learned about the way the radical imagination echoes between social movements, cultural producers, and intellectuals, not only within particular struggles and locales but globally in an interconnected age. This approach affirms Marcel Stoetzler and Nira Yuval-Davis’s (2002) argument that the imagination is not some transcendental universal force but a situated one, contingent on how it is diversely expressed and articulated in bodies intersected by the forces of racialization, gender expression, sexuality, citizenship, ability, and so on.

I have argued that financialization has a very particular relationship to the imagination and in many ways vitally undermines the possibility of radical imagination (Haiven 2014b). Let us pause for a moment to recognize the terrifying reality that the derivatives contracts and financial assets that today hold our neoliberal globalized economy together—and indeed, the financial debts that constrain our lives—are, essentially, imaginary: they do not exist in the “real world” except to the extent that they are held in place by the institutional cultures of belief within and among financial institutions and intermediaries. As such, we should see the financial world as, at least in part, a vast orchestration of the imagination of millions of social actors, the coordination of them into shared narrative practices of value making with horrifically real power. I have proposed that Marx’s category of “fictitious capital” remains useful, first, because it helps name the power and prominence of unproductive, speculative wealth churning around the globe (see also Bello 2013; Lapavitsas 2013) but also, secondarily, because, in an age when the financial economy is intimately connected to the debt economy, the financialization of all our imaginations is vital to the system’s survival. Not only does it rely on the endless proliferation of national debts, student debt, medical debt, and credit card debt, but it also targets and is systematically invested in the abject debts of subprime and microfinance borrowers.

Tragic Settler Storytelling; or, A Financial Literacy of the Radical Imagination

We might be well served by understanding financialization, at the level both of major institutions and of our everyday lives, as a practice of storytelling and future making. When framed as fictitious capital, credit, debt, speculation, and risk all come into focus as means to narrate and thereby manage the relationship between actors and material forces in a sublimely complicated world (see Jameson 1997; La Berge 2015; Toscano and Kinkle 2015). Under the rule of financialization, we come to tell the stories of our individual and collective futures through the language of speculation, risk management, and personalized investment, translating almost all aspects of our lives into individual opportunities or liabilities (see Haiven 2014a). Institutions including universities recalibrate themselves around measurements of risk management and return on investment, and governments increasingly see their responsibilities to citizens as the [End Page 360] minimization of systemic risk and the facilitation of personal and corporate risk taking. As Martin (2007) perceptively notes, the future ceases to be a sacred space of radical possibility and is instead profaned, subjected to endless speculation and measurement in the name of securitization.

Hence, little latitude remains for the radical imagination based on the idea that the future might be very different indeed. If, as Khasnabish and I have argued (Haiven and Khasnabish 2014), the radical imagination emerges not from the private mind but from social cooperation, the increased isolation and individualism germane to financialization strangle our individual and social lives of opportunities to dream of, discuss, debate, and pursue different futures together.

This is the tragic nature of what I want to call financial illiteracy, which not only is the plight of those who have not enjoyed access to information about household budgeting and tax returns; it is a social epidemic. It is, on the first and primary level, an illiteracy to the realities of financialization that I have been discussing, specifically the racialized dimensions of financialization. Second, it is an illiteracy toward the infrastructures of racism, colonialism, and other modalities of oppression and exploitation that financialization both depends on and reinforces. Third, it is an illiteracy toward the manifold potentials for alternative forms of social cooperation and relationality that financialization forecloses.

What would a form of financial literacy look like based in the radical imagination? I have identified five animating principles, though they are by no means exhaustive. First, such a financial literacy would need to take as its key objective to reveal and make readily apparent that debt and financialization are not merely the results of the actions or choices of individuals but the product of structural and systemic forces. These forces are augmented by institutional power and technological acceleration and have taken on monstrous power over our world and our local experiences of it (see Ross 2014).

Second, the shape of financial power resonates with and in many ways perpetuates and refurbishes long-existing systems and structures of power organized around race, class, gender, sexuality, citizenship status, colonialism, imperialism and environmental destruction. Third, these power relations are complex, intersectional, and coevolving and demand sustained and critical inquiry to understand, unpack, and challenge. They play out not only among political and financial elites but also at the level of all social institutions and in our own daily lives. Fourth, these systems and structures are held in place, reproduced, and normalized by stories, narratives, metaphors, and fictions, but, on the bright side, they can equally be questioned, challenged, problematized, and subverted by the mobilization of strategic stories, narratives, metaphors, and fictions.

Fifth, confronting or overcoming financialization and its impacts on our lives is not simply a matter of individual actions and knowledge but a process of collective and community reinvention, resistance, and solidarity. Fictitious capital is ultimately a method for imagining and ordering social cooperation on a grand scale. It is a poisoned and poisonous form of care. Thus, in addition to vociferous protests demanding regulation, as well as manifestations and organizations that demand revolutionary social change, we must find ways of imagining and cooperating differently, beyond financialization’s reach, of transforming and replacing social institutions, and of learning to care for and relate to one another, and the rest of the earth’s inhabitants, anew. [End Page 361]

Toward a Decolonial Financial Literacy?

I am called to account for Stoetzler and Yuval-Davis’s (2002) notion of the radical imagination: it must always be situated in the bodies and relationships of its bearers. As such, for me, a settler subject within the state of Canada and a beneficiary of a settler-colonial system, part of this process would begin by studying the links between settler colonialism and financialization and the ways in which the two are historically and presently intertwined. This would take up the thread accidentally dropped in the First Nations Financial Fitness booklet, which, in spite of itself, hinted at the promise of another, decolonial economics underneath. The mainstream colonial microeconomic thinking that undergirds most financial literacy campaigns would consign practices like the potlatch to its own long-transcended prehistory, naming it a form of “primitive” and mystical exchange superseded by the evolution of money, credit, debt, and financial infrastructures (see Graeber 2011; Sahlins 1972).

But if we take seriously the idea that the potlatch was an alternative form of economic practice with its own set of literacies as (if not more) sophisticated as Wall Street’s necromancy, we can use it to hold “our” own settler-colonial tradition of financialization up to productive scrutiny. The decolonial work for settlers is not to seek to fully understand or claim the potlatch as our own; such would be an act of violent cultural appropriation (see Hopkins 2011) and also a romanticization of a grounded, particular tradition. Rather, by recognizing the potlatch as a possible form of financial literacy and practice, we call into question the otherwise unstated or unrecognized assumptions that support our own settler-colonial financial practices and the social, economic, and ecological violence they enact.

A decolonial financial literacy might also concern itself with recognizing and acknowledging the debts that a settler society owes and a fundamental reconsideration of what repaying or offering restitution for those debts would mean. Some of these debts are literal. For instance, the Canadian government currently owes potentially billions of dollars to Indigenous nations for the rental of land and resources of their lands, monies that have been held in “trust” for generation after generation (Alfred 2009; Six Nations Lands and Resources Department 2010).

These are only the literal, financial debts—the historical and moral debts go much deeper. Legal settlements around the genocidal abuse of Indigenous people in residential schools, as meager as they have been, give us a small indication of the scope of such obligations (Borrows 2014; Henderson 2015). They are being joined, slowly, by suits from the survivors (or descendants of survivors) of other, similarly genocidal government programs (see Spencer 2017). We might also add the suits that are pending, or ought to be pending, for the destruction of Indigenous people’s lands and livelihoods thanks to the forms of environmental racism and outright resource theft since before Canada’s foundations (see Ilyniak 2014; Mascarenhas 2014; Shkilnyk 1985). We might add the suits of all those Indigenous people who, because they were stripped of their status by the Indian Act (because they didn’t have the correct blood quantum, or because they or their ancestors broke some government-imposed rule), have not had the opportunity to benefit from their rights as enshrined in the treaties (Bhandar 2016; Hanson 2009).

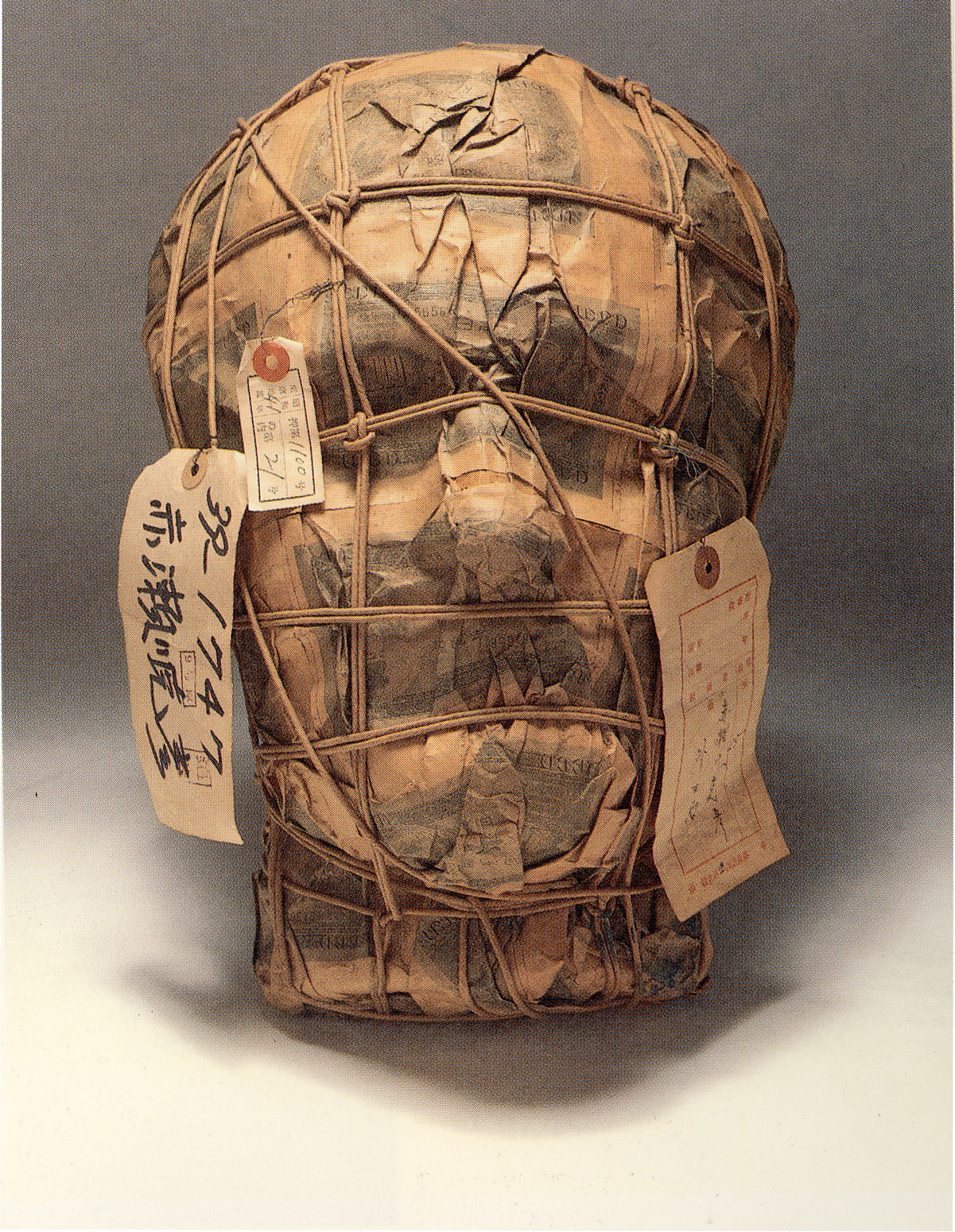

Then there is a case for the purely economic damage done to Indigenous communities through the vicissitudes of [End Page 362] the racist Indian Act, which, for instance, withheld full fiduciary rights from Indigenous people for generations (and still), ensuring they and their members would never gain access to the same means of financial investment that enabled settlers and settler communities to develop their infrastructure and capacities (see Pasternak 2015; Vowel 2016). We could also speak of the debt for all those (already insufficient) funds and resources that were (and are) diverted from Indigenous communities by the agents and bureaucrats of the (recently renamed) Department of Indian Affairs (see Manuel and Derrickson 2015). We might include here the debt incurred by the Canadian government (and, by extension, its citizens and beneficiaries) by the outlawing of the potlatch ceremonies described earlier, from 1884 to after WWII, a prohibition that explicitly sought to undermine the independent West Coast Indigenous economy and only one of many examples of systematic efforts to undermine Indigenous sovereignty and autonomy (Alfred 2009). Here, not only am I talking about the tangible, material debt for all those thousands upon thousands of Indigenous artifacts and objects of art and ritual that were seized by the Canadian state and later given, sold, or loaned to museums in Canada and around the world (when they weren’t simply destroyed, despoiled, or stolen by colonial enforcement officers) (see Phillips 2012). I am also talking about the debt for a systematic econocide.

And then there are the unpaid debts for the land itself. It is by now widely acknowledged that the vast majority of historical treaties were signed based on a (convenient) fundamental colonial misunderstanding, or under extreme duress (Asch 2014; Borrows 2010; Gehl 2014). Appropriate compensation for these lands has not been offered or agreed to in the vast majority of cases. And, indeed, even by settler legal precedent, the compensation should at least approximate the reasonable expectation of future enjoyment and profit that has been denied to Indigenous people and communities thanks to the loss of this “resource.” (This is, for instance, the principle that guides the hypothetical compensation to corporations if Canada or other member nations abrogate such neoliberal trade treaties as the North American Free Trade Agreement.)

In Defense of Bankruptcy

In all likelihood, were Canada to attempt to repay these debts, even in part, it would be bankrupt. The compound debt owed to Indigenous people is, essentially, immeasurable. But, in reality, the settler-colonial state is already bankrupt, and it always was. Even by its own laws, the nation’s claims to legitimacy are tenuous, based as they are on colonial violence and expropriation (Mackey 2016). Yet on a fundamentally deeper level this bankruptcy represents a moral rot at the heart of the nation that, while it has enriched itself and some of its citizens (mostly the white, male ones; see Smith 2006) based on the expropriation, exploitation, and destruction of Indigenous lands, remains fixated on achieving wealth and success by feeding omnicidal financialized capitalist markets (Coulthard 2014). More profoundly, this bankruptcy is felt in the form of a highly alienating and nihilistic society that has essentially been created to facilitate the private accumulation of settler wealth based on the principles of competition and exploitation (see Lowman and Barker 2015; Cornell and Seely 2015).

Much, much more can be, has been, and should be said about each of these points, but time here does not permit. Suffice it for now to say that observations [End Page 363] like these, and others, would need to be central to a form of decolonial financial literacy, one that fundamentally undermines not only the financialized notion of debt and credit but also of wealth itself. While by neoliberal accounting, Canada is a wealthy, G8 nation (though one would be hard-pressed to recognize it, given the rhetoric of state austerity), on another, deeper level, an audit of Canada as a settler-colonial state reveals it is not only tremendously in debt to the point of financial bankruptcy but also dwelling in an abject cultural and moral poverty.

Such an accounting, such a literacy, would need to be based, as well, in maneuvers that would sever settler subjects from their fidelity to the state and the capitalist system it serves (see Lowman and Barker 2015). The conscription of settlers has always depended on making settlers into financialized subjects ready to partner with that state (and economy) for their own enrichment. And some (generally though not exclusively white, male) have indeed become rich, by the measurements of the settler-colonial capitalism: dollars in the bank, material property, exclusively owned land (see Day 2016). But to succeed, theoretically and politically, such a decolonial financial literacy would have to go beyond merely demanding that the misbegotten wealth of settlers and the settler-colonial state writ large be reclaimed or redistributed. It would also depend on educating ourselves to recognize value very differently (see Haiven 2014b).

It would not, for instance, be sufficient only to imagine (re)appropriating houses, lands, mines, factories, cities, institutions, and resources to redistribute them, first, to compensate Indigenous people for their losses and, second, perhaps, to distribute them more equally among settlers. Rather (or in addition), it would require a reimagination of wealth itself. Certain allegedly wealth-producing assets, such as the Alberta Tar Sands and most large-scale mines, would likely need to be recognized as actually destructive of the wealth of the nonhuman world (and also of human health) and abolished. This would unavoidably have dramatic effects on the Canadian economy, at least in terms of its competitiveness with other capitalist nation-states. Taken to its full extent, it may economically bankrupt the nation within the global capitalist economy as it exists. And somehow this would need to be seen not as a loss but as a collective liberation, not simply for Indigenous people but for settlers as well.

Hence, a radical, decolonial financial literacy has to take seriously what it would mean to share responsibility and love for the land and recognize it as the source of our wealth (see Armstrong 2007). And it would need to do more than simply generate sorrow and shame based on settlers’ evident collective debts: it would need to show that reconciliation is more than the balancing of financial accounts. The only way to “repay” such debts would be to decolonize the land, which is to say repatriate it to Indigenous nations (see Tuck and Yang 2012), and transform settlers into collective subjects worthy of living on and caring for the land with its other human and nonhuman inhabitants.

Such an exercise is not merely a matter of intellectual learning and theoretical conjecture. It is learned on the front lines, when settlers break ranks with the settler-colonial state and the capitalist economy and make common cause with Indigenous land defenders (see Coulthard 2014). In this sense, the protest camp or the blockade, such as the dramatic convergence around the Standing Rock Sioux protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016 and 2017, is the institution of this [End Page 364] new financial literacy, a place where debts and credits are bestowed and paid not in money but in solidarity and where a certain fitness is exercised (see Barker and Ross 2017). We are, in these struggles, learning to become literate in our own powers.