The following essay will appear in the journal ephemera in a special 2024 issue dedicated to games, accompanied by a print-at-home edition of CLUE-ANON, the game therein described. It emerges from the Conspiracy Games and Countergames project I have pursued with Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou and A.T. Kingsmith.

Why play games with conspiracies? A reflection on the board game CLUE-ANON

Max Haiven

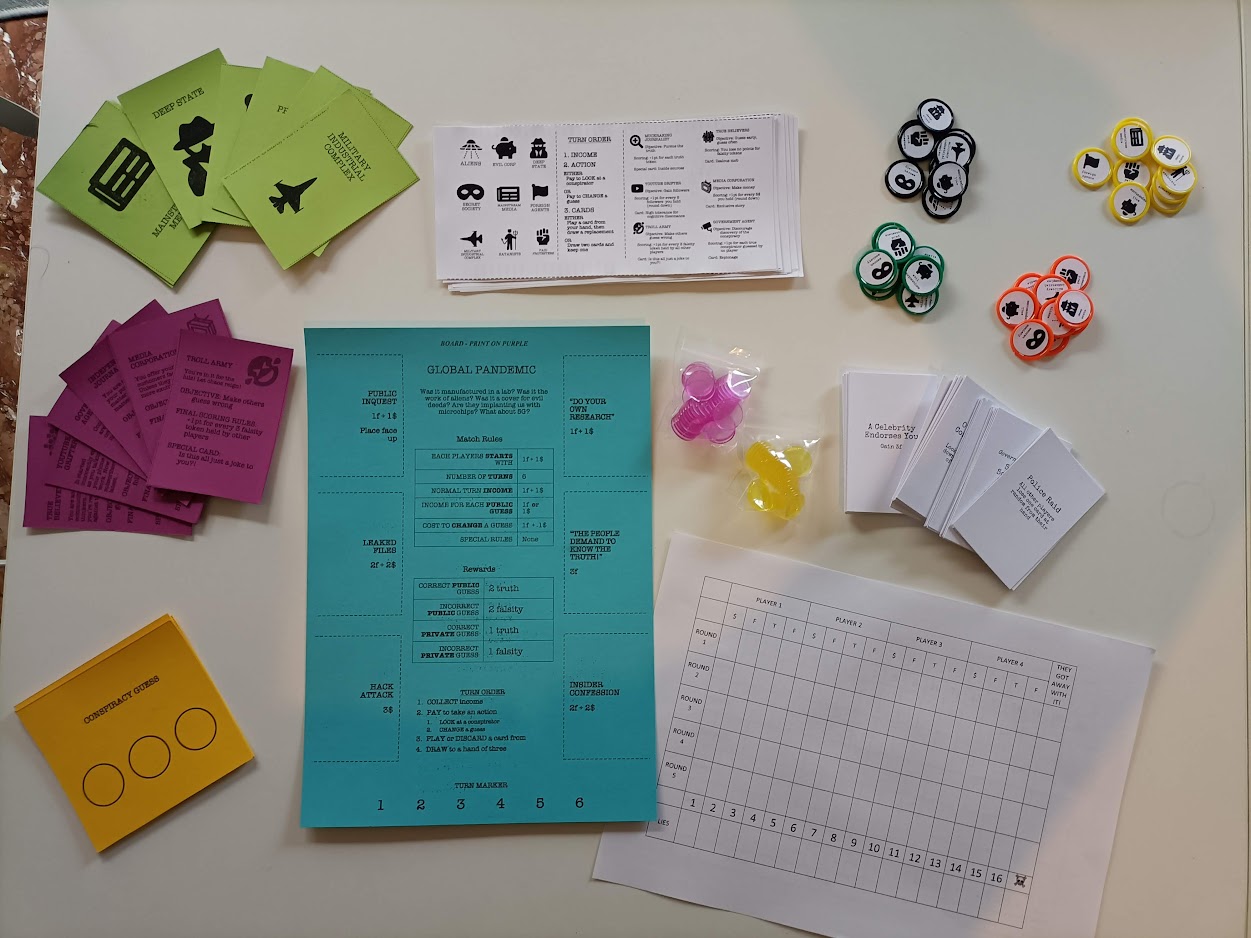

CLUE-ANON is a board game of deduction and bluffing for 3-to-4 players that fosters a fun, generative environment to discuss why conspiracy theories are so appealing…and so dangerous. It borrows its name and theme not only from the popular commercial murder-mystery board game Clue (marketed as Cluedo in some countries), but also from the wildly popular Q-Anon ‘conspiracy fantasy’, which holds that there is a secret war against a vast global conspiracy of powerful elites and celebrities who are controlling governments in order to kidnap and abuse children.

I developed the game as part of the Conspiracy Games and Countergames project, which I led along with Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou and A.T. Kingsmith, who also offered invaluable feedback and ideas for the game’s development. The motivation to create the game stemmed from students explaining to us that they dreaded returning home at holidays to family members deeply and belligerently enthralled to the reactionary conspiracy fantasy. Indeed, a number of critics have likened Q-Anon to a massive, addictive, participatory ‘alternate reality’ game, with very real consequences, including being a major driver of the storming of the US Capitol on 6 January 2021. We wondered: could we craft a game our students could take home to catalyze critical conversations about how ‘viral’ conspiracy fantasies form? And might it in any way help by capturing or redirecting some of the ludic energy or impulses that otherwise find such problematic expression in reactionary conspiracism?

In CLUE-ANON, players role-play as actors and influencers in the conspiracy media sphere. The game is played across two or three ‘matches’, each of which revolves around a different conventional American conspiracy scenario: who faked the moon landing? Who assassinated the beloved politician? Who rigged the important election? Who unleashed the global pandemic?

At its most basic level, the game is simply one of deduction: there are nine possible ‘suspects’, represented on cards (the Deep State, Space Aliens, an Evil Corporation, Satanists, the Mainstream Media, Foreign Spies, a Secret Society, the Military Industrial Complex, and Paid Protesters). Of these nine suspects, the three ‘real conspirators’ are placed under the board until the end of the match. The remaining six are arranged, face-down, on the board. Players have six turns to pay in-game resources (money and followers) to privately look at those six face-down cards in order to try and deduce the three hidden ‘real conspirators’ and solve the conspiracy.

But wait, here is where things get interesting, in two ways. First, it’s impossible to get enough resources in six turns to look at all six suspect cards…unless one bluffs! Players can gain more money and more followers if they publicly announce they believe one or more of the suspects is involved in the conspiracy, even if they have little or no evidence on which to base this accusation. This, of course, is a parody of our sad reality, where the proponents of bogus, premature, and unsubstantiated conspiracy theories are often richly rewarded in a highly monetized social media landscape. But after six turns the real conspirators are revealed, and players with incorrect accusations on the table might lose points, so they must balance their strategy.

And here’s the real twist: a successful player’s strategy will be influenced by the character they have been randomly assigned at the start of the game and that they keep secret until the very end, after all the conspiracies have been explored. While almost all the characters gain points for correctly guessing the three real-conspirators, each character also has a powerful end-of-game bonus that has a large impact on who wins or loses. The Independent Journalist gains extra points if their opponents also guess correctly, encouraging them to help their adversaries. But all players have an incentive to pretend to be the journalist. For example, the Troll Army gains points if they can misdirect their opponents and cause them to guess incorrectly. The Social Media Corporation gets a big bonus for accumulating money. The True Believers get a bonus for gaining as many followers as possible. The State Agent gains when everyone is so distracted by lies the real conspirators get away with it. At the very end of the game, after all the conspiracies are solved, all players can try and guess one another’s characters for extra points, and so there is an incentive to keep one’s character somewhat secret, even while seeking to maximize its scoring bonus.

In the rest of this paper, I will reflect on some of the motivations and influences for developing CLUE-ANON with special attention to the potential of games as research tools and the their particular usefulness for exploring conspiracism and other disturbing phenomena in an age characterized by the disenchantment of digital capitalism.

Games as research tools

The Conspiracy Games and Countergames (CGCG) project, of which CLUE-ANON is a part, also included a research podcast and collaborative writing activities. That project evolved in 2021 out of a previous set of inquiries into the nature of the phenomenon of ‘anxiety’ under digital capitalism (see Haiven and Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022b). We began from the idea that, sociologically speaking, conspiracism is a response to capitalist anxieties. But neither anxiety nor conspiracism are inherently pathological: there is plenty to be anxious about in digital capitalism, and real conspiracies are a crucial part of its political economy (Haiven, Kingsmith and Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022b). Further, both the category of ‘anxiety’ and of ‘conspiracism’, while they seek to identify real phenomena, are themselves socially constructed and shaped by the power relations and force fields of digital capitalism, and therefore require reflexive scrutiny (Kingsmith, 2023).

None of the three researchers involved in the project had any prior expertise in conspiracies and conspiracism: I am a cultural theorist of social movements and financialization; Komporozos-Athanasiou is a social theorist who shares with me a specialization in finance and the imagination; and Kingsmith’s dissertation concerns the politics of anxiety and mental health. The CGCG project is part of a wider set of efforts to embrace the insights that come from being a scholarly neophyte, and to make that learning public. For example, we used the project’s interview-driven podcast as a way to learn together, making the vulnerable process of discovery accessible to a wider audience of other scholars as well as artists, activists, and community-members. We triangulated a topic (conspiracies, games, and digital capitalism) and, through our research, found and reached out to diverse guests who we felt might have something to say about two or more of its elements.

CLUE-ANON was also part of this process. When we began our collaboration, I proposed to my colleagues developing a board game whose objective would not simply be to gamify our research conclusions as a means to publicize our conclusions but, rather, to be a reflexive research tool. I wanted to explore how making a game could be part of the research process, rather than an outcome of it. I didn’t simply want the game to communicate our theories and findings; I wanted to see if the process of developing and refining the game could be part of the way we did research, and a way to include others in it. Even more particularly, I wanted to see if such a game could not simply to measure the responses of players (we have never used CLUE-ANON to gather data) but, rather, as a catalyst for conversations that might inform the process of scholarly theorization.

Of course, the use of games as a pedagogical platform is ancient, and the development of ‘serious games’ for the purposes of enhancing military or business strategy, or educational outcomes, fosters a large international industry (see Michael and Chen, 2006). The design of the smaller subset of serious games known as ‘social impact games’, which strive to address injustices or power imbalances in society, requires the designer to distill the relevant sociological information and model down to its more basic elements before operationalizing them (Flanagan, 2009). It’s one (relatively easy) thing to simply layer a thematic ‘skin’ on an existing or even a new game – for example, modifying the graphic design and narrative elements of a well-known game like Monopoly to gesture towards a process like contemporary gentrification. Without disparaging that approach, I have found it more rewarding to try and develop a game from the ground up that explores a social and political topic through the game’s ‘procedural rhetoric’: the game should ‘teach’ the player through the way it invites them to develop their own strategies, beyond the particular graphical and narrative trappings (Bogost, 2010). In CLUE-ANON, players teach themselves to balance the requirements of discovery and deception based on the particular bonuses of their character. They learn, in playing, the seductive exhilaration of conspiracism.

In some sense, I am curious about the way that a game might excite what C. Wright Mills (2000) called ‘the sociological imagination’: the ability to reckon with the dialectic relation between the individual and society, to see how social forces articulate and are articulated by people, bridging the gap between history and biography. There is something unique about the way games (particularly tabletop games) place players in an artificial hiatus, or liminal space, between structure and agency, which I think is particularly well-suited to awakening this kind of imagination (Nguyen, 2019). To this extent, I think that some games can encourage what I might call a proto-theoretical approach. By encouraging players to think in complex, multi-directional, even contradictory ways, to think metaphorically about society, and to think about agency, it might set the stage for them to then do the work of theorizing their society anew. Such a process would be ideological in the counter-hegemonic sense: it might contribute to empowering players to think beyond dominant and conventional explanations for social phenomena and, instead, produce a new cognitive map. Elsewhere, I have written with Alex Khasnabish about the opportunities critical scholars might embrace to ‘convoke’ the radical imagination. Here, convocation names an interventionist research strategy that aims to bring people together to explore how the world could be different and ponder what prevents or might enable change (Haiven and Khasnabish, 2014). Games, I think, can be part of this process. This conviction is fortified by the theories of Hans-Georg Gadamer (1986), Johann Huizinga (1971), Roger Caillois (1961), David Graeber (2014), and others, for whom play is a central dimension of human experience, creativity and politics.

The value of broken games

So CLUE-ANON represented, in a sense, a research tool: a supplement to the process of systematic thinking. Since I first developed the game, I have substantively revised it over 15 times based on feedback and information I gained while playtesting it with the assistance of my colleagues A.T. Kingsmith and Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou. Through that iterative process, I have learned a great deal not only about the game in particular and game design in general, but also about the triangulated theme of conspiracism, gamification, and digital capitalism that we three set out to explore. I have also learned a great deal about this theme through my conversations with players after the game, where, typically, they reflect on both the game itself and the sociopolitical theme.

In particular, I have found it helpful to ask players: ‘how could this game be more realistic?’. As a game, rather than a simulation, CLUE-ANON strives not only for some degree of sociological mimesis, but also to be fun. In the gap between what the game pretends to model (the mediascape of conspiracism) and the social reality of gameplay (typically wwith people who don’t consider themselves conspiracists, let alone influencers), a lot can be learned. It’s what we can learn from the dissonance that matters. When I ask the question, many interesting research questions naturally arise. Is CLUE-ANON a game only about American conspiracism, or to what extent can it map onto other, often quite different, contexts? The Independent Journalist is given a rather heroic role in the game, striving to get others to see the truth – but is that realistic or naïve (and what does ‘independent’ even mean)? Does the fact that there is a ‘real conspiracy’ to discover in the game imply that someone did actually fake the moon landing, or intentionally unleash the global pandemic, and with what consequences? Could the game accidentally encourage conspiracism, rather than warn against it? Do such warnings even work? Does the fact that the game includes implausible suspects (satanists, space aliens) make too much of a mockery of conspiracism, when in fact we know that conspiracies (in terms of powerful people working together in secret) do really exist and that supernatural conspiracy theories, while sensational, are relatively harmless compared to their political counterparts? Does the complexity of the game preclude it ever actually being a resource to dissuade would-be conspiracists from descending down the proverbial ‘rabbit hole’? And perhaps most importantly, does the game actually encourage critical thinking, and is that a sufficient end unto itself? Sufficient in what sense? Each question opens onto a profound question that goes well beyond the game itself and touches on topics including the allure and power of conspiracism, the promise and peril of games and gamification, and the sociology of ideology and belief.

It is these kinds of questions that the game, ultimately, aims to convoke. The game is unavoidably didactic in many ways, but ultimately in what I hope are generative ways: players are encouraged to explore and question their frustrations and misgivings. I have playtested the game dozens of times, at academic conferences, in university classrooms, with social justice activists, and at game cafes and other board game-focused spaces. It never fails to generate an interesting conversation, in part because it is slightly frustrating. CLUE-ANON is an imperfect game, made by an amateur designer without (as of yet) the support of a game company that might help improve its internal balancing mathematics, its graphic design, or its playability. It is not fluid or unfrustrating to play. It does not ‘accurately’ model or simulate the world of conspiracism; it is perhaps best seen as an ironic parody that inflates, embellishes, and renders fantastic some elements of conspiracy culture as a means to open the door for critique. But in some senses, the broken-ness of the game in several ways contributes to its usefulness. I often ask playtesters, ‘what would you do to fix this game?’ or ‘what would make for a better game on this theme?’, which invites them to enter into the very thought processes that led me to create it.

Creating CLUE-ANON has convinced me that creating and playing an imperfect game can be an important part of a creative, open-ended social research process, not simply because it offers an avenue to explore scholarly ideas, but also because it brings other people into the process.

Dangerous games and enchanted inquiry

As Komporozos-Athanasiou, Kingsmith, and I have written elsewhere, the CGCG project is motivated in part by a debate currently forming among scholars and commentators about the gamified elements of contemporary conspiracism (Haiven, Kingsmith, and Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022b). The emergence of the Q-Anon phenomenon led a number of game designers and scholars to remark on and explore the game-like qualities of the movement. In a widely cited Medium article published during the height of media attention towards Q-Anon, game designer Reed Berkowitz (2020) observed the way the conspiracy played on its adherents attraction to a collective process of discovery, similar to the mechanics he employed when making augmented reality games. While mainstream American conspiracy journalist Mike Rothschild (2022) largely dismissed the idea that Q-Anon is a huge, malevolent game, the 2021 HBO docu-series Q-Anon: Into the Storm explores the proposition in depth, even linking its emergence to key players in the augmented- and alternate-reality gaming world. In his exceptional exploration of Q-Anon, Wu Ming 1 (the pseudonym of a member of the left-wing Italian writing collective Wu Ming) also explores the game-like aspects of the conspiracy, although he is careful to link it to a much longer history of conspiracism as a kind of dangerous public play, with often terrifying consequences (Wu Ming 1, 2021; Haiven, Kingsmith and Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022a). More recently, Hugh Davies (2022) has with greater rigor asked to what extent Q-Anon employs gamified elements.

We may never know the degree to which the Q-Anon conspiracy fantasy was intentionally concocted by far-right political actors, nor the extent to which they may have been inspired by games and game design. However, the associations certainly alert us to the continuity between games and participatory conspiracism, in which the absence (or enigmaticness) of a central authority allows followers/players to concoct their own endless role-playing scenario (Haiven, 2023). In the CGCG project we ask: if so much social imagination is being employed towards the perpetuation of such an ever-evolving collective fantasy, what otherwise unanswered social needs is it fulfilling for its adherents? And to what other ends might this imaginative surpluss be put (Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022)? Is this energetic field one that can only produce a proverbial storm of destruction, such as the one unleashed on 6 January 2021 when Q-Anon devotees joined thousands of other far-right activists in a blundered coup attempt at the US Capitol? Or could these energies be generated and directed elsewhere?

Inspired by such a question, Komporozos-Athanasiou, Kingsmith, and I have proposed to explore what we are calling, tentatively, enchanted inquiry. Our approach takes as its Weberian starting point the idea that digital capitalism is profoundly disenchanting, in the sense that it compels most social actors to instrumentalize almost all aspects of their life as a means to leverage some measure of success or even stability in a chaotic neoliberalism-ravaged economy without any guarantees. To many, perhaps most, digital capitalism feels like an unwinnable game. While reason, science, and ‘progress’ may have once been seen as the keys to a better life, today many would entertain the notion that they have, in many ways, made the world worse. Of course, both right-wing and left-wing anti-modernism is nothing new, but its articulations in our times of triumphant global capitalism, rising ethno-nationalism and ubiquitous social media are profound. In such a circumstance, it is perhaps unsurprising that people across the political spectrum turn to fantasy and what we frame as tactics of collective re-enchantment.[1] Usually, these re-enchantments appear relatively harmless: the rise of computer and role-playing gaming, for example, or the turn (back) to horoscopes and astrology (see Komporozos-Athanasiou, 2022). But sometimes these forms of collective re-enchantment aim to assert their concocted alternate realities on the broader reality of which they are a part, sometimes violently. The editor of and contributors to the recently published collection Catastrophe Time! (Zhang, 2023) meditate on the weird and disturbing trends that emerge at the intersection of culture, politics and economics in a moment when financialization and the media and sociality it produces ruptures even the dominant capitalist cosmology that gave rise to financialization in the first place. In line with these observations, our conjecture is that games and gaming are important sites of re-enchantment and, even more importantly, they might offer critical scholars a key point of intervention beyond simply trying to distribute better information or offer more reliable analysis.

Many scholars and commentators across the political spectrum have called for a war on disenchantment. Stephen Pinker’s Enlightenment now (2018) is perhaps a singularly popular and cogent example of a genre of writing that insists we return to reason, rationality, evidence, and argumentation in the face of a rising tide of fantasy. Reactionary online celebrities like Ben Shapiro or Jordan Peterson have likewise branded themselves as the voices of reason and the paladins of the embattled Enlightenment. As scholars, we three collaborators at CGCG deeply and profoundly value many principles associated with the Enlightenment and reason, and have dedicated our careers to education based on these principles. However, we are skeptical of this strategy, even when proposed by figures we admire, like linguist and political theorist Noam Chomsky, whose dedication to disenchanted reason stems from his left-wing anarchist beliefs. We have revisited Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1997), for example, to recall how these august virtues have, in the hands of instrumentalist modern regimes (both state-socialist and capitalist), been turned against human needs and used to perpetuate vast and irrational injustices. We also are inspired by several generations of feminist and anti-colonial thought which has demonstrated how the fetish of ‘reason’ and the reification of the Enlightenment worldview have long been instruments of patriarchy and a racial world system (Haraway, 1991; Mies and Shiva, 1993; Wynter and McKittrick, 2015).

Yet our curiosity is drawn towards what possibilities might exist for critical scholars to engage with the turn towards collective re-enchantment on its own grounds. CLUE-ANON is one tentative example. As a social board game, and especially one that requires role-playing, it is a tool of collective enchantment. Games, as Johan Huizinga (1971) famously theorized, create a temporary ‘magic circle’ within which a parallel reality is generated through consensual play. If that’s true, then perhaps we can think about games as mobile laboratories for exploring society, much in the same way physicists are able to – in miniature forms and for (relatively) tiny spans of time – generate antimatter and other theorized phenomena in a controlled laboratory environment. One element of such a process that appeals to me in particular is that it facilitates the collaboration of scholars and theorists with non-specialists. This opens the door to new, unanticipated insights at the same time as it can be a profound learning opportunity for all involved.

Unfortunately, most commentators intuitively believe that the most important element in the fight against the dangerous dimensions of collaborative re-enchantment (of which the Q-anon phenomenon is emblematic) is the debunking of false beliefs through sound argumentation (see Gilroy-Ware, 2020). The idea that conspiracists are self-involved, paranoid idiots is depressingly common, and profoundly wrong. Many people are attracted to conspiracism because it offers them a community of people who want to stand up to or at least understand the world of injustice and lies they find around them. Likewise, the idea that conspiracists simply parrot what they have read online is asinine. In fact, in most cases, conspiracists are highly creative (perhaps to a fault) and do exhaustive, often obsessive research. They are, for the most part, not hypo-critical thinkers by hyper-critical thinkers. While their procedures of that research and creativity can and should be critiqued, the impulse and the dedication are substantial. As Erica Lagalisse (2019) argues, if we are honest, the line between conspiracy theories and the critical theories in which readers of ephemera might trade is by no means clear, although the distinction perhaps begins with the way they respectively frame power as either biographical (this or that person or institution is acting in an evil way) or systemic.

I do not believe CLUE-ANON will convince a dedicated Q-Anon believer to abandon their fantasy. At best, it might help to redirect the urge towards re-enchantment in those not yet in the grips of such a fantasy. It aims to be part of channeling the sociological imagination towards more generative and critical forms of collective inquiry before it can be seduced by conspiracism. At a minimum, the game has been an important part of developing the theoretical paradigm that has informed our collective work in the CGCG project, and indeed this paper itself.

References

Adorno, T.W. and Horkheimer, Max (1997) Dialectic of enlightenment. London and New Rok: Verso.

Berkowitz, R. (2020) ‘A game designer’s analysis of QAnon’, The CuriouserInstitute (Medium.com). [https://medium.com/curiouserinstitute/a-game-designers-analysis-of-qanon-580972548be5]

Bogost, I. (2010) Persuasive games: the expressive power of videogames. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

Caillois, R. (1961) Man, Play, and Games. New York: Free Press.

Davies, H. (2022) ‘The Gamification of Conspiracy: QAnon as Alternate Reality Game’, Acta Ludologica, 5(1): 60–79.

Flanagan, M. (2009) Critical Play: Radical Game Design. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gadamer, H. (1986) The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays. Translated by Robert Bernasconi. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gilroy-Ware, M. (2020) After the fact? the truth about fake news. London: Repeater.

Graeber, D. (2014) “What’s the Point If We Can’t Have Fun?” The Baffler 24. [https://thebaffler.com/salvos/whats-the-point-if-we-cant-have-fun]

Haiven, M. (2023) “From Financialization to Derivative Fascisms: Some Cultural Politics of Far-Right Authoritarianism in an Era of Unmanageable Risk.” Social Text 41(2): 45–73.

Haiven, M. and A. Khasnabish. (2014) The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity. London and New York: Zed Books.

Haiven, M., A. T. Kingsmith, & A. Komporozos-Athanasiou. (2022a) ‘Interview with Wu Ming 1: QAnon, Collective Creativity, and the (Ab)uses of Enchantment.’ Theory, Culture & Society, 39(7–8): 253–268.

Haiven, M., A. T. Kingmsith and A. Komporozos-Athanasiou. (2022b) ‘Dangerous Play in an Age of Technofinance: From the GameStop Hunger Games to the Capitol Hill Jamboree’, TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies, 45: 102–132.

Haiven, M. and A. Komporozos-Athanasiou (2022) ‘An “Anxiety Epidemic” in the Financialized University’, Cultural Politics, 18(2): 173–193.

Haraway, D. (1991) Simians, cyborgs, and women: the reinvention of nature. London and New York: Routledge.

Huizinga, J. (1971) Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Boston: Beacon.

Josephson-Storm, J. (2017) The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Kingsmith, A. T. (forthcoming 2023) Anxiety as a weapon: An affective approach to political economy. Athabasca, AB: Athabasca University Press.

Komporozos-Athanasiou, A. (2022) Speculative communities: living with uncertainty in a financialized world. Chicago and London : The University of Chicago Press.

Lagalisse, E. (2019) Occult Features of Anarchism. Oakland, CA: PM Press.

Michael, D. and S. Chen. (2006) Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train and Inform. Boston: Thomson.

Mies, M. and V. Shiva. (1993) Ecofeminism. Halifax NS: Fernwood.

Mills, C.W. (2000) The sociological imagination. Fortieth Anniversary edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Nguyen, C.T. (2019) ‘Games and the Art of Agency’, The Philosophical Review, 128(4): 423–462.

Pinker, S. (2018) Enlightenment now: the case for reason, science, humanism, and progress. New York: Viking.

‘Q: Into the Storm’ (2021). Dir. Cullen Hoback. HBO.

Rothschild, M. (2022) The Storm Is Upon Us: How QAnon Became a Movement, Cult, and Conspiracy Theory of Everything. New York: Melville House.

Wu Ming 1. (2021) La Q di Qomplotto: Come le fantasie di complotto difendono il sistema. Rome: Alegre.

Wynter, S. and K. McKittrick. (2015) ‘Unparalleled catastrophe for our species? Or, to give humanness a different future: Conversations’, in K. McKittrick (ed.) Sylvia Wynter: On being human as praxis. Durham NC and London: Duke University Press: 9–89.

Zhang, Gary Zhexi. (2023) Catastrophe Time! London: Strange Attractor.

[1] It’s also worth sounding a note of skepticism towards the idea that modernity is, in fact, as disenchanted as we imagine (see Josephson-Storm 2017).