The following text will appear in a forthcoming issue of South Atlantic Quarterly (SAQ) later in 2023.

Abstract

Can board games be part of challenging the dangerous tide of reactionary cultural politics presently washing over the United States and many other countries? We frame this threat to progressive social movements and democracy as entangled with a cultural politics of reenchantment. Thanks in part to the rise of ubiquitous digital media, capitalism is gamified as never before. Yet most people feel trapped in an unwinnable game. Here, a gamified reactionary cultural politics easily takes hold, and we turn to the example of the Q-Anon conspiracy fantasy as a “dangerous game” of creative collective fabulation. We explore how critical scholars and activists might develop forms of “enchanted inquiry” that seek to take seriously the power of games and enchantment. And we share our experience designing Clue-Anon, a board game for 3-4 players that aims to let players explore why conspiracy theories are so much fun… and so dangerous.

Keywords

Games and gamification; digital capitalism; disenchantment; conspiracy theories and conspiracism; board games

Board games as social media within, against and beyond reactionary capitalism: Towards an enchanted inquiry

Max Haiven, A.T. Kingsmith and Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou

2023-02-18

This essay argues that, in a moment when capitalism integrates games and gamification, cultural politics are increasingly marked by the appearance of participatory forms of play that seek to re-enchant a disenchanted world. Games have played a significant role in the social, political, and technical reproduction of late capitalism, especially its digital social media platforms. This occurs at the same time that life under neoliberal capitalism is felt by many as if trapped in an unwinnable game in a disenchanted world. This feeling is important to the cultural politics of our current moment. We take up the Q-Anon conspiracy fantasy as an important example of the way people play “dangerous games” together in (reactionary) response to this state of affairs. We also explore some of the ways the urge towards re-enchantment and participatory play elsewhere along the political spectrum. We conclude by previewing an experimental board game we developed, titled CLUE-ANON, which is intended to provide an alternative critical scholarly intervention: a form of play that moves away from the urge to debunk and disenchant by engaging instead with participatory reenchantment head-on.

Games, the first social media?

The common use of the term social media refers to the engagement with recent digital platforms. But this approach unfortunately tends to obscure many of the other social activities that the digital revolution has enabled and their consequences for politics and activism (Fuchs 2021). This paper focuses on board games, a social media avant la lettre, and one that has quietly become consequential to an emerging cycle of movement struggles.

The kinds of objects and activities we, today, understand as board games have an ancient lineage (Masukawa 2016). The progenitors of board games may predate written language, and variations are abundant around the world. In another sense, board games as we know them are quite recent, with origins dating back to the commercial printing press (Flanagan 2009). Recent years have seen a massive expansion of the industry and the popularity of board games among a variety of consumers (Lutter and Weidner 2021). This process was well underway even before the Covid-19 pandemic and was spurred by the development of popular new games (notably the blockbuster success of Settlers of Catan) and the ways new digital retail platforms like Amazon circumvented the gatekeeping function of brick-and-mortar stores. User-driven platforms like the dominant Board Game Geek also helped players discover new games and develop a fan-base that encouraged independent designers and publishing companies to develop more specialized products (Wachs and Vedres 2021). The development in the 2010s of online platforms for playing board games remotely amplified this trend. Crowdfunding platforms have allowed independent game-makers and small game companies to produce high-quality games in ways that were not possible before, when the costs of developing, testing, designing, manufacturing and distributing board games placed the industry in the hands of a few dominant companies.

Of the many gaming subcultures to emerge over this period, several oriented themselves towards social movements for collective liberation and struggles for radical progressive social change. Already in the earliest days of commercial board games, the medium was recognized as a platform for efforts to educate players about politics, history, morality and appropriate behavior. It was also widely used as a platform for satirical social commentary (Booth 2015). In 1908, first-wave feminist activists in England published Suffragetto, which simulated the struggle between the London police and militants for women’s right to vote. The most famous example of a board game as a vehicle for social commentary was The Landlords’ Game, a critique of the rapacious greed of property speculators, which was later bastardized into a glorification of economic parasitism and marketed as Monopoly (Donovan 2017, 71–88). In 1978 Marxist philosopher Bertel Olman (2002) notoriously published Class Struggle, a Monopoly-like board game in which players take on the role of bourgeoisie and proletariat who seek to make alliances with other class factions (small business, farmers, students). The game ends either in revolution or nuclear annihilation.

By the 1980s, many social movement-aligned game makers were eschewing the conventional competitive idiom and designing cooperative games that aimed to instill feminist and other social justice values (Ross n.d.). In the 2010s and early 20s social justice and activist oriented companies like TESA and games like Bloc-by-Bloc (which simulates anarchist urban insurgency) or Spirit Island (which reverses the colonial narrative of Settlers of Catan and sees players act cooperatively as Indigenous people working with powerful spirits to clear an island of settlers) were common in North Atlantic activist circles (Fair 2022). At the same time LARPing (Live Action Role-Playing) grew increasingly popular as a means to both have fun and think anew about social justice topics (Torben 2020). We are currently amidst a renaissance of independent game design, partly enabled by digital platforms for playing and sharing games. Independent designers self-publish print-at-home games that profoundly challenge the competitive, individualist, accumulative and heroic idiom that we associate with conventional board games. Their games focus instead on (anti-)colonialism and Global South perspectives on disability, on queerness, and that advance with feminist principles (Fair 2022; Mukherjee and Hammar 2018; Ross n.d.).

Board games appeal to advocates and allies of movements for radical social change for a number of reasons. Successful games are easy to learn, quick to play and, importantly, fun. They promise to convey an underlying message in an attractive and charismatic form. The turn towards board games was motivated in part by the concern of movement organizers for the education of young people, who typically enjoy and learn through games. Further, as game theorist Ian Bogost (2010) suggests, games teach not only through their particular manifest narratives and self-evident design features, but through their “procedural rhetoric”: the way the playing of the game itself, and the strategic thinking it demands of players, implicitly teaches players something relevant about their social world. Particular games are, in some sense, always taking place within bigger social, political and economic “games,” and often it is the broader, unacknowledged “game” that is the real focus of the players attention (Boluk and LeMieux 2017).

Importantly, on a deeper level, games offer their players access to a primordial human passion for seemingly purposeless play, something that pivotal game theorist Johannes Huizinga (1971) sees at the core of society. The ability to draw what he calls a “magic circle” around a group of consenting players and define a mutually pleasurable parallel world may be older than language and is not only evidenced in humans but many other species as well. Education theorists have noted that games offer one of the most effective venues for learning, and indeed structured play is arguably the most important method by which humans learn from infancy onward (Crocco 2011). It should then come as no surprise those involved in struggles for radical social change should gravitate to what might well be considered the first among social media.

Indeed, the first generation of social media as well as its later forms drew implicitly and explicitly from games and gaming (Hristova and Lieberoth 2021). Notoriously, Facebook was first developed in a college dorm room as a game through which male students could rank the attractiveness of their female counterparts. Twitter’s development drew on insights from game design and the company hired game designers to help make their platform more attractive. Instagram continues to advertise itself as a “fun” game-like environment for online play, even though it has become seriously personally and professionally consequential to hundreds of millions of users and the lucrative platform for the careers of “influencers.” And TikTok, most explicitly, fosters a game-like experience of back and forth performative play, a kind of participatory “infinite game,” to draw on James Carse’s (1986) terminology: a game where the primary objective is to keep playing.

Dangerous Games in the reactionary cultural politics of late capitalism

It is not surprising that both establishment-oriented and reactionary forces have gravitated towards the power of games. Over the last four decades, capitalism has become an increasingly gamified force (deWinter, Kocurek, and Nichols 2014; Jagoda 2013; Tulloch and Randell-Moon 2018).

On the one hand, we have seen the explosion of gaming industries, notably the video game industry, which today rivals other major entertainment media like film, television, sports and gambling (Dyer-Witheford and De Peuter 2009). The board game industry is nowhere nearly so large or concentrated, in part because board games require vastly fewer resources to create and bring to market, encouraging more diversification. But it nonetheless cannot be easily separated from the profit-driven pressures that shape the broader games industry of which it is a part.

On the other hand, as digital gaming advances and handheld digital devices become ever more ubiquitous, all manner of corporations and social institutions have gravitated towards using the protocols, methods and idioms of gaming to stimulate particular behaviors and dispositions in consumers, usually in the name of making money (Hon 2022). This builds on a long history of companies advertising their products in games or sponsoring the creation and marketing of games as a means to attract consumers (Terlutter and Capella 2013). But something today is different. The handheld devices that are increasingly ubiquitous, as well as the apps created for them were inspired by a previous generation of gambling machines (Schüll 2014). Based on careful study of neurosciences and usage patterns, these machines aim, among other things, to encourage dependency and sustained focus among users (Zuboff 2019).

But we must also broaden the scope when we think about games, gamification and digital capitalism. As we have argued elsewhere (Haiven, Kingmsith, and Komporozos-Athanasiou 2022), capitalism feels, to many if not most working- and middle-class people, as if it were an unwinnable, compulsory game. The post-war compromise of Fordism suggested that those (in the so-called First World) who obeyed legal and social conventions and “played by the rules” could be relatively certain of some meaningful if modest share of growing prosperity, at least for white male workers. In the neoliberal period, however, social and economic risks were shifted onto consumers and workers, sold as the freedom to compete in an all-powerful market presented as a “level playing field” (Littler 2017). Far from rewarding hard work, cunning and determination, most workers’ real wages declined during this period, as economic life increasingly felt like a rigged game.

Unfortunately, given the state of media and educational institutions, a large number of people affected by these conditions have been deprived of, or are unconvinced by, critical analyses of the political and economic source of these frustrations. Because of this, many were and are seduced by reactionary narratives that insisted the unfairness of the situation was due to specific groups cheating or rigging the game (Hochschild 2016). The far right has made and continues to make considerable gains in the public imaginary by fostering narratives that frame “special interest groups” as sabotaging the field of fair play. In the United States, accusations of welfare fraud, the misappropriation of state assistance, the cynical manipulation of “affirmative action” policies, the cheating of the criminal justice system and the abuse of guilt-inducing social justice rhetoric have renovated anti-Black racism with murderous effect (HoSang and Lowndes 2019). Fears that millions of unregistered migrants are cheating what many erroneously imagine to be a “fair” immigration system have been manipulated with devastating efficacy. Avowed white supremacists fearing a “great replacement” but also many people of non-white migrant backgrounds, have come to resent those assumed to have “cheated” in the game they themselves won by hard work and sacrifice (Brass 2021). Such fears also fuel a resurgence of anti-Semitic conspiracy theories that present Jews as sadistic secret game-masters, pulling the levers of an infernal machine intended to both seduce and cheat honest gentiles (Wu Ming 1 2021).

Within this context, the right-wing and reactionary turn to games and gaming is hardly surprising. Gaming subcultures had long been hostile to women, but this exploded onto the public stage in 2014 with the infamous #GamerGate phenomenon, which saw legions of gaming fans, almost all of whom identified as men, orchestrate a decentralized but highly effective campaign of life-threatening harassment of women and feminist game designers and critics (Massanari 2017). Recognizing the demographic significance of gamers as a constituent base and admiring their vitriol, far-right strategist Steven Bannon pivoted towards courting these communities through the now-infamous Breitbart news enterprise and later mobilized them in the successful presidential campaign of Donald J. Trump (Warzel 2019).

Both these far-right initiatives relied upon game-themed tropes that insisted that good, hard-working, honest people had been cheated out of their right to participate in the economic game of neoliberal capitalism. The implicit feeling was not that they had been derived of their inherent entitlements, but of their right to compete, fairly, for success. They also invited far-right activists to mobilize in game-like formations, including crowd-sourced social media mobbings reminiscent of #GamerGate, where targets were identified from the bully pulpit to be harassed. Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign can fruitfully be seen as a kind of spectacular (and spectacularly dangerous) game. The crass and bombastic candidate constantly “broke the rules” of acceptable politics to court both, on the one hand, far-right stalwarts who agreed with his racist ideology and, on the other, unaffiliated but disaffected voters who generally felt cheated. For both admirers and critics, consuming and reacting to Trump’s atrocious virtuosity had a game-like quality, a vivified, high-stakes version of the “reality TV” game-show The Apprentice that had returned the iconic player to the limelight.

Meanwhile, the same “whitelash” culture of resentment was giving rise to previously unseen monsters. As early as 2017, in the netherregions of the dark-web, a mysterious character who named himself “Q” began to post cryptic messages about current events, building a small subcultural following that quickly went viral as Q claimed to be an insider in the Trump administration, part of a top-secret taskforce helping the then-President uncover and wage war on a secret conspiracy (Rothschild 2022). In this conspiracy, senior members of the Democratic Party, along with seemingly random A-list celebrities, corporate power-holders and other people and institutions were part of a global cabal dedicated to kidnapping, abusing, murdering and harvesting the vital fluids of children.

During the pandemic the Q-anon conspiracy fantasy grew quickly in popularity, perhaps thanks to the support of Trump insiders and sympathizers who saw it as a vehicle to rally support to the embattled President. As it moved from the subcultural margins to the mainstream, numerous game designers noted the unsettling game-like qualities of the phenomenon. Q’s dark-web messages to his followers were profoundly cryptic and suggestive, encouraging online communities to form dedicated to a kind of participatory hermeneutics. A group of derivative social media and video platform celebrities emerged as trusted interpreters. Some crusading fans would take it upon themselves to gather at sites they imagined were soon to be crucial locations in the great war on the pedophile conspiracy, as prophesied by Q. Game designer Reed Berkowitz (2020), who specializes in the design of augmented reality games, presented the term “guided apophenia” to describe how the protagonists behind Q-Anon were taking advantage of the human capacity to see or imagine patterns, even where none exist. For Berkowitz and others, Q-Anon was nothing so much as a massive, largely decentralized participatory online game, with very dangerous consequences (Davies 2022).

Tensions came to a head on January 6, 2020, when supporters of the unseated President stormed the US Capitol building, leading to the deaths of six people and one of the most infamous cases of civil insurgency in living memory. News reports during and after these grave events made much of the strange costumes and playful demeanor of many of the “insurgents,” as well as the prevalence of self-identified Q followers who believed the final confrontation with the evil cabal was finally at hand. In the media and congressional inquiries that followed, much of the discussion focused on to what extent the mob had been orchestrated and encouraged by the Trump administration campaign, and the extent of the involvement of organized white supremacists and other extreme right groups.

What has, however, fallen by the wayside, is a sociological investigation of the playful motivations and subjectivities of not only the particular participants, but the many supporters of the events. To be curious about the ways that the events of January 6 represented, for many, a game gone horribly wrong is not to diminish it as a failed far-right putsch, but to recognize the way that it was also symptomatic of the cultural politics of gamified neoliberal capitalism.

An age of reenchanted cultural politics

Our argument is that such gamified cultural politics has been not only indispensable to the rise and spread of reactionary conspiracism, but also part of a wider set of attempts to re-enchant the world. Adorno and Horkheimer (1997) famously built on Max Weber’s (2001) theory to argue that, while technocratic, scientific and actuarial logics of protestant-led European capitalism had stripped the world of its enchantments, the instrumentalization of life had displaced the need for enchantment to a new level. While a number of theorists have challenged this view (McCarraher 2019; Josephson-Storm 2017), we still find much merit in such a description, especially as it helps us reflect on the cultural politics of the neoliberal age where each individual is intended to adopt the dispositions of the financier, craftily transmuting all aspects of life (relationships, housing, pastimes, talents) into assets to be leveraged under the sign of the indifferent market (Haiven 2014). The neoliberal dream of pursuing peace, prosperity and freedom through universal competition and a market-driven society turned out to be just as enchanted a worldview as any other. Beyond the pretensions of the self-deluding middle classes (who believe that they, too, can be rich, if only they play their cards right) the imposition of an austere market logic affects nearly every person, normalized through “high-functioning” anxieties that internalize the dominant capitalist narrative of productivity above all else (Kingsmith 2022). Even for the poor and economically marginalized, the figure of the hustling petty criminal, or the rags-to-riches reality TV starlet, offer a model for how to transmute life into a series of market plays and puts for “players” who can “game the system.” The fact that, today, a huge proportion of adolescents aspire to be influencers via monetized and gamified social media platforms indicates how deeply a game-like market logic has saturated social life.

It is amidst widespread disenchantment that we contextualize the game-like turn described above and, in particular, the appeal of what at first glance seem like absurd conspiracy fantasies. Part of this has something to do with the narrative tropes and simplified feelings of ideological closure propounded in popular cultural texts (notably Hollywood films), with their stark, manichean depictions of good and evil. The plot line that sees a small band of misfits coming together against insurmountable odds and the skepticism of their fearful compatriots to bring down a cruel regime is now extremely common in film, television and video games, including in children’s content. In a disenchanting world where one’s sense of purpose is reduced to participating in what feels like a rigged economic game, it should not be particularly surprising that individuals take up these tropes to craft immersive and enchanting parallel worlds. When economic reality becomes a near-impossible yet compulsory game, many people escape into or create games that feel empowering, prosocial and at least theoretically winnable.

Here, the Q-Anon participatory fantasy is only the most stark example, relatively easy to recognize because it sits so squarely on the absurd far-right of the political spectrum. Yet those who preen themselves as centrists are no less culpable for creating participatory fantasies. While Trump’s policies were atrocious, and while the fascistic political culture he presided over are extremely dangerous, the “centrist” loathing of him that reduced the problems of late capitalism to his particular evil exemplified a kind of enchanted and enchanting narrative just the same (Bratich 2020). Anti-Trump online politics even included forms of politicized witchcraft (Fine 2021), but this is only the most extreme example of the turn towards game-like re-enchantment.

Meanwhile, we should not ignore the many ways that those on the radical left, those who advocate for radical social change, are also attracted by a cultural politics of re-enchantment. For example, in recent years many young people on the Left have turned towards astrology and divination, including horoscopes, tarot cards and more (Komprozos-Athanasiou 2021; Sparkly Kat 2021). This is part of a wider trend towards a cultural politics that centers healing and “the work” of inward-facing subjectivity transformation, based on the recognition that systems of oppression work, in part, on the level of the subject. It is also based on a growing skepticism of the white-supremacist mobilization of tropes of objectivity and rationality. Critics may be tempted to bemoan the “weird” turn in the Left as a departure from not only reason but also the working class, seeing it as purely a self-indulgent middle-class narcissism. However, we prefer to read it sociologically as emerging from, and as a (dubiously effective) response to, the same political economic circumstances that give rise to the “cosmic right” (Milburn 2020; O’Donovan 2021).

Forms of reenchantment present themselves as resistance, even though in many cases they help perpetuate, reinforce or defend dominant structures and systems of power. We have opted for a language of enchantment, rather than simply fantasy, to signal the way that this tendency is not simply a completely fictitious parallel world but a set of dispositions that incorporate and offer interpretive frames for real-world events to animate a wide diversity of groups and orientations across the political spectrum in ways that rely not simply on the individual fabrication of a “common sense” imaginary, but operate through participatory social frameworks (Haiven and Khasnabish 2014).

There are many critics who, in the face of reenchanting politics, call for a return to a civics of disenchantment. Across the political spectrum we can hear clarions to return to Enlightenment principles that encourage the disinterested adjudication of evidence over fantasy. Stephen Pinker’s (2018) Enlightenment Now is only the starkest of these arguments. More generally, the rise of conspiracy theories and post-truth politics has seen a wide variety of commentators raise the tattered banner of reason against the hydra of reenchantment. Yet as Marcus Gilroy-Ware (2020) argues, such efforts come after years of conspicuous mistruth and fabrication by governments (around, for example, the War on Terror) and the everyday cynical manipulation of truth and perception by the marketing and public relations industry.

In this context, calls to “return to reason” are not only ineffective, they are themselves another example of a game of neoliberal reenchantment: performative speech acts that serve to align the author and his (for it is almost always a man) readers as self-ennobling reasonable subjects, beset on “all sides” by unreasonable, monstrous zealots. In other words, from one angle the advocates of disenchantment invite their audience into a kind of heroic narrative game every bit as enchanting as the game-like enchantments they decry.

Clue-Anon and the promise of enchanted inquiry

What, then, are critical scholars, working in solidarity with radical movements, to do in such a material context? If even calls to “return to reason” are themselves a kind of re-enchanting game, where do those of us stand who are reproduced by and who are tasked with reproducing the university, that bastion of disenchantment? We have no clear answers, but we have experiments, and these experiments try to inhabit and leverage, rather than condemn and dismiss, the urge towards reenchantment.

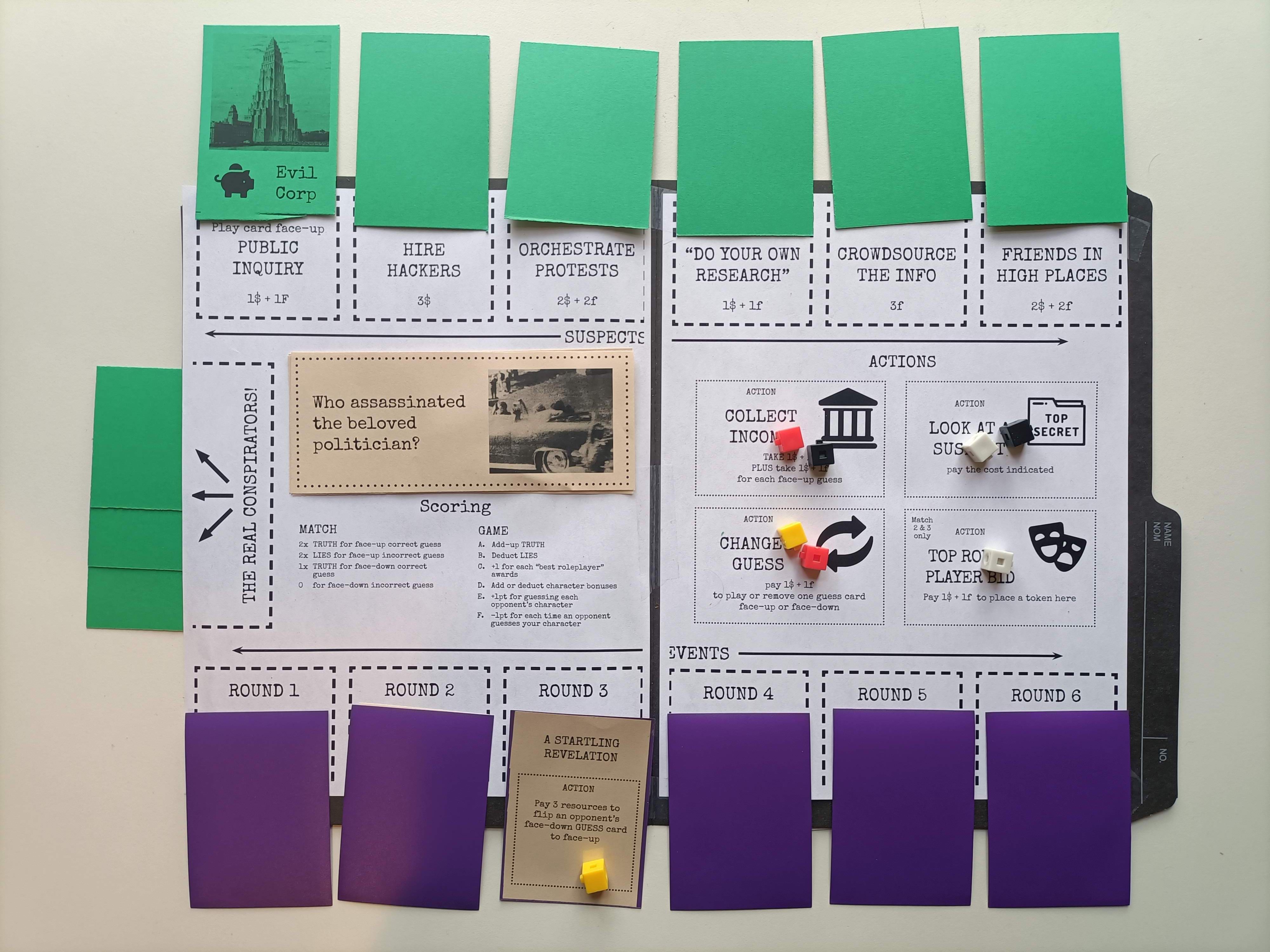

In 2020 our research team began to experiment with creating a board game intended to harness the power of participatory reenchantment. It was motivated in part by testimony from our students that revealed many of them feared visiting their families at holidays to find their loved-ones in the grips of powerful and seemingly unshakable conspiracy fantasies. Several of these students reported that board games offered a collective pastime that avoided inflammatory conversations. Based on these reports, and on our ongoing research, we began to develop a game (designed by Max Haiven and refined collectively with Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou and A.T. Kingsmith) that, after several iterations finally arrived at the name CLUE-ANON.

This four-player competitive game is intended to take 90 minutes and is played over three rounds. In each round, the players seek to deduce the identity of three hidden “real conspirators” from a set of nine possible suspects. To do so, they pay in-game resources (money and followers) to look at the remaining six suspects. However, to gain sufficient money and followers, and to fool others, players must prematurely declare their conspiracy theory, well before the evidence warrants it. At first glance, it seems that the objective of the game is to correctly guess the “real” conspirators. However, in a twist, each player is assigned a secret character with a unique motivation. These characters have been drawn from the mediasphere that surround contemporary gamified, digitally-driven conspiracism. While the Independent Journalist gains extra points if their opponents also learn the real conspiracy, the Troll Army gains extra points if they can lead their opponents to guess incorrectly. The Social Media Corporation wins if they accumulate a lot of money, while the YouTube Grifter seeks to accumulate money and followers, the truth be damned.

What results is a fast-paced, somewhat chaotic game of deduction, bluffing and role-playing. In the process of play, the players learn that, in the conspiracy game, the truth is rarely anyone’s first objective. Role-playing characters with different but obscured motivations encourages a creative estrangement from one’s own position. The game is designed to be fun and easy to learn. The conspiracy theories, characters and scenarios in the game are comical, but based on real-world examples (who created the SARS-COV2 virus? Who faked the moon landing?), opening the doorway after the game for stimulating conversation. The experience generated by the game is non-didactic, in the sense that it does not explicitly attempt to teach a message but, rather, to create a space for critical conversation. Yet through the playing of the game, players come to understand that conspiracy theorizing is a fun, prosocial activity, and that one can easily become enchanted with the creative inventiveness of shared, competitive storytelling.

The game has now been played by hundreds of people, including groups at the Athens School of Fine Arts, the Singapore Civil Service College, University College London’s Institute of Advanced Studies, the ephemera journal’s “Games, Inc.” conference and the Copenhagen IT University’s Centre for Digital Play. Many players and designers find the game overly complex: it’s hard to strategize when there are so many motivations, elements and narratives in play; that’s quite the point, we reply.

Our hope is that the game can provide an important tool for educators and activists to catalyze conversations not only about the dangers and seductions of conspiracism, but its lures and emancipatory possibilities too. We see it as the first step towards a methodological orientation we have speculatively named enchanted inquiry, for which we would like to set out some hallmarks.

First, enchanted inquiry does not primarily seek to debunk, disenchant or dispel misinformation. Rather, it begins from the premise that globalizing neoliberal capitalism gives rise to the urge to reenchant the world. Without letting go of a sanguine assessment of the profound dangers such tactics of reenchantment might awaken or exacerbate, enchanted inquiry begins with the question: how might this propensity be redirected or channeled towards more critical, illuminating and generative ends? It aims, in other words, to demonstrate that we are always in the process of reenchanting the disenchanted world and to make this process more democratic, egalitarian, responsible, care-full and non-coercive.

Second, in this regard, enchanted inquiry draws on and helps develop the scholarly dispositions encouraged by Max Haiven and Alex Khasnabish in their 2014 book The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity. There, they argue it is not sufficient for researchers simply to observe and report on social movements in the name of valourizing them in academic contexts (a strategy they call invocation), nor to simply collapse themselves into social movements in the name of solidarity (a strategy they call avocation). Rather, scholars can adopt a strategy of convocation, “calling together” diverse social movement actors to deepen their conceptual, theoretical and political understandings and practices–the radical imagination–through facilitated discussion, debate and deliberation. Here, the scholar-activists recognize themselves not only as the outside expert or the embedded participant but (also) a third thing: a facilitator of the radical imagination, that tectonic force at the core of all societies and all subjects that arises to challenge the given reality in the name of manifold possibilities for changing society (Castoriadis 1997). Enchanted inquiry is one method (or perhaps an orientation that might inform many methods) for embracing this strategy of convocation with a particular focus on games, mystery, magic, myth and speculative imagination.

Finally, enchanted inquiry is fun, in the nuanced, plural and collaborative sense. Enchanted inquiry draws on theories of play and games in order to create seductive circumstances where participants can learn about the world together and change their minds in non-trivial ways. Fun here does not mean simple, easy or uncritical. The ambivalence of the word speaks to the challenge of making activities that are both challenging and rewarding, prosocial and deeply reflexive, enjoyable and disruptive. Enchanted inquiry aims to mobilize fun as a means to catalyze the radical imagination.

References

Adorno, Theodor W., and Horkheimer, Max. 1997. Dialectic of Enlightenment. London: Verso.

Berkowitz, Reed. 2020. “A Game Designer’s Analysis of QAnon.” The CuriouserInstitute, September. https://medium.com/curiouserinstitute/a-game-designers-analysis-of-qanon-580972548be5.

Birchall, Clare. 2001. “Conspiracy Theories and Academic Discourses: The Necessary Possibility of Popular (over)Interpretation.” Continuum 15 (1): 67–76.

Bogost, Ian. 2010. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Boluk, Stephanie, and Patrick LeMieux. 2017. Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Booth, Paul. 2015. Game Play: Paratextuality in Contemporary Board Games. New York and London: Bloomsbury.

Brass, Tom. 2021. “Great Replacement, or Reaping the Capitalist Whirlwind (via Populism/Nationalism).” In Marxism Missing, Missing Marxism: From Marxism to Identity Politics and Beyond, 230–57. Leiden and Boston: Brill.

Bratich, Jack. 2020. “Civil Society Must Be Defended: Misinformation, Moral Panics, and Wars of Restoration.” Communication, Culture and Critique 13 (3): 311–32.

Carse, James P. 1986. Finite and Infinite Games: A Vision of Life as Play and Possibility. New York: Free Press.

Castoriadis, Cornelius. 1997. The Castoriadis Reader. Translated by David Ames Curtis. Oxford and Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Crocco, Francesco. 2011. “Critical Gaming Pedagogy.” The Radical Teacher, no. 91 (September): 26–41.

Davies, Hugh. 2022. “The Gamification of Conspiracy: QAnon as Alternate Reality Game.” Acta Ludologica 5 (1): 60–79.

deWinter, Jennifer, Carly A. Kocurek, and Randall Nichols. 2014. “Taylorism 2.0: Gamification, Scientific Management and the Capitalist Appropriation of Play.” Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds 6 (2): 109–27.

Donovan, Tristan. 2017. It’s All a Game: The History of Board Games from Monopoly to Settlers of Catan. New York: St. Martin´s Press.

Dyer-Witheford, Nick, and Greig De Peuter. 2009. Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Fair, Hannah. 2022. “Playing with the Anthropocene: Board Game Imaginaries of Islands, Nature, and Empire.” Island Studies Journal 17 (1): 85–101.

Fine, Julia Coombs. 2021. “Orange Candles and Shriveled Cheetos: Symbolic Representations of Trump in the Anti-Trump Witchcraft Movement.” In The Anthropology of Donald Trump, edited by Jack David Eller. London and New York: Routledge.

Flanagan, Mary. 2009. “Board Games.” In Critical Play: Radical Game Design, 63–119. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fuchs, Christian. 2021. Social Media: A Critical Introduction. 3rd edition. London: SAGE.

Gilroy-Ware, Marcus. 2020. After the Fact? The Truth about Fake News. London: Repeater.

Haiven, Max. 2014. Cultures of Financialization: Fictitious Capital in Popular Culture and Everyday Life. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Haiven, Max, and Alex Khasnabish. 2014. The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity. London and New York: Zed Books.

Haiven, Max, A.T. Kingmsith, and Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou. 2022. “Dangerous Play in an Age of Technofinance: From the GameStop Hunger Games to the Capitol Hill Jamboree.” TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 45 (October): 102–32.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 2016. Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right. New York: New Press.

Hon, Adrian. 2022. You’ve Been Played: How Corporations, Governments, and Schools Use Games to Control Us All. New York: Basic Books.

HoSang, Daniel, and Joseph E. Lowndes. 2019. Producers, Parasites, Patriots: Race and the New Right-Wing Politics of Precarity. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hristova, Dayana, and Andreas Lieberoth. 2021. “How Socially Sustainable Is Social Media Gamification? A Look into Snapchat, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.” In Transforming Society and Organizations through Gamification, edited by Agnessa Spanellis and J. Tuomas Harviainen, 225–45. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Huizinga, Johan. 1971. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Boston: Beacon.

Jagoda, Patrick. 2013. “Gamification and Other Forms of Play.” Boundary 2 40 (2): 113–44.

Josephson-Storm, Jason Ānanda. 2017. The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

Kingsmith, A. T. 2022. “The Problem of High Functioning Anxiety.” Mad In America. October 25, 2022. https://www.madinamerica.com/2022/10/high-functioning-anxiety/.

Komprozos-Athanasiou, Aris. 2021. Speculative Communities. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Littler, Jo. 2017. Against Meritocracy: Culture, Power and Myths of Mobility. London ; New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Lutter, Mark, and Linus Weidner. 2021. “Newcomers, Betweenness Centrality, and Creative Success: A Study of Teams in the Board Game Industry from 1951 to 2017.” Poetics 87 (August): 101535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101535.

Massanari, Adrienne. 2017. “#Gamergate and The Fappening: How Reddit’s Algorithm, Governance, and Culture Support Toxic Technocultures.” New Media & Society 19 (3): 329–46.

Masukawa, Koichi. 2016. “The Origins of Board Games and Ancient Game Boards.” In Simulation and Gaming in the Network Society, edited by Toshiyuki Kaneda, Hidehiko Kanegae, Yusuke Toyoda, and Paola Rizzi, 9:3–11. Singapore: Springer Science.

McCarraher, Eugene. 2019. The Enchantments of Mammon: How Capitalism Became the Religion of Modernity. Cambridge, MA and London: Belknap.

Milburn, Keir. 2020. “The Cosmic Right Is on the Rise in the UK. The Left Must Fight It With Reason.” Novara Media. September 4, 2020. https://novaramedia.com/2020/09/04/the-cosmic-right-is-on-the-rise-in-the-uk-the-left-must-fight-it-with-reason/.

Mukherjee, Souvik, and Emil Lundedal Hammar. 2018. “Introduction to the Special Issue on Postcolonial Perspectives in Game Studies.” Open Library of Humanities 4 (2): 33.

O’Donovan, Órla. 2021. “COVID-19 and the Counter-Collective Collective Organizing of the Cosmic Right.” Community Development Journal 56 (3): 371–74.

Ollman, Bertell. 2002. Ballbuster?: True Confessions of a Marxist Businessman. 2nd edition. Brooklyn, NY: Soft Skull Press.

Pinker, Steven. 2018. Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. New York, NY: Viking.

Ross, Nica. n.d. “Gaymers: Bootlezzing the Archives.” Nica Ross (Artists’ Website). Accessed February 18, 2023. https://nicaross.com/Gaymers-Bootlezzing-the-Archives.

Rothschild, Mike. 2022. The Storm Is Upon Us: How QAnon Became a Movement, Cult, and Conspiracy Theory of Everything. New York: Melville House.

Schüll, Natasha Dow. 2014. Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Sparkly Kat, Alice. 2021. Postcolonial Astrology: Reading The Planets Through Capital, Power, and Labor. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Terlutter, Ralf, and Michael L. Capella. 2013. “The Gamification of Advertising: Analysis and Research Directions of In-Game Advertising, Advergames, and Advertising in Social Network Games.” Journal of Advertising 42 (2–3): 95–112.

Torben, Quasdorf. 2020. “Turning Votes into Victory Points. Politics in Modern Board Games.” Gamevironments. https://doi.org/10.26092/ELIB/403.

Tulloch, Rowan, and Holly Eva Katherine Randell-Moon. 2018. “The Politics of Gamification: Education, Neoliberalism and the Knowledge Economy.” Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 40 (3): 204–26.

Wachs, Johannes, and Balázs Vedres. 2021. “Does Crowdfunding Really Foster Innovation? Evidence from the Board Game Industry.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 168 (July): 120747.

Warzel, Charlie. 2019. “How an Online Mob Created a Playbook for a Culture War.” The New York Times, August 15, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/15/opinion/what-is-gamergate.html.

Weber, Max. 2001. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Translated by Talcott Parsons. London and New York: Routledge.

Wu Ming 1. 2021. La Q Di Qomplotto: Come Le Fantasie Di Complotto Difendono Il Sistema. Rome: Alegre.

Zuboff, Shoshana. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. New York: Public Affairs.