An edited version of following text will appear later in 2023 as part of the Global Visual Handbook of Anti-Authoritarian Counterstrategies, published by the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. It offers a glimpse of the game Clue-Anon, developed by Max Haiven with Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou and A.T. Kingmsith.

Clue-Anon, gaming conspiracy, and the anti-authoritarian imagination

Max Haiven, Aris Komporozos-Athanasiou, and A.T. Kingsmith

11 theses on gaming conspiracies

1. In a disenchanted era of relentless work and worry, the lure of reactionary conspiracy theories is driven by the promise of meaning and community.

2. Capitalism’s advocates claim it provides humanity’s first and only level playing field. But most people feel trapped in a ruthless game they have no hope of winning.

3. In the condescending view of the dominant intelligentsia, the conspiracist is a lonely crank, bordering on psychotic. But conspiracists often build worlds that foster pleasure, collective fun and connection. Their worldbuilding is a dangerous form of play.

4. The powers-that-be tell us education is the key to remedying conspiracism; but hegemonic education is part of the problem that gives rise to conspiracism in the first place.

5. Corruption and collusion have always been part of capitalism’s systemic contradictions. To deny this is foolish. But to simply imagine capitalism is simply one big conspiracy is dangerous, misleading and intoxicating.

6. If conspiracy fantasies are the “poor person’s cognitive mapping” in the disorienting totality of capitalism, then the role of intellectuals cannot be to merely provide more accurate maps. It must be to convoke experiences of radical map-making.

7. Liberal critiques of conspiracies admit that inequality breeds resentment, which in turn fuels disinformation. But capitalism is also inherently alienating, and its enclosure of the human desire for play drives us towards dangerous conspiratorial play.

8. Mainstream commentators bemoan the “falling rate of reason” in what they see as a world beset by irrationality. But they refuse to recognize this is symptomatic of an irrational profit-driven system, where reason is everywhere instrumentalized.

9. In a disenchanted world, the far right has weaponized conspiracy theories to destroy the thing we call reality and open new theatres of violent play and revanchist re-enchantment.

10. Our work as counter-conspiracists, who believe a better world is possible, must include seizing the means of enchantment.

11. So far critics have only tried to debunk the worlds of conspiracies, the point, however, is to game them.

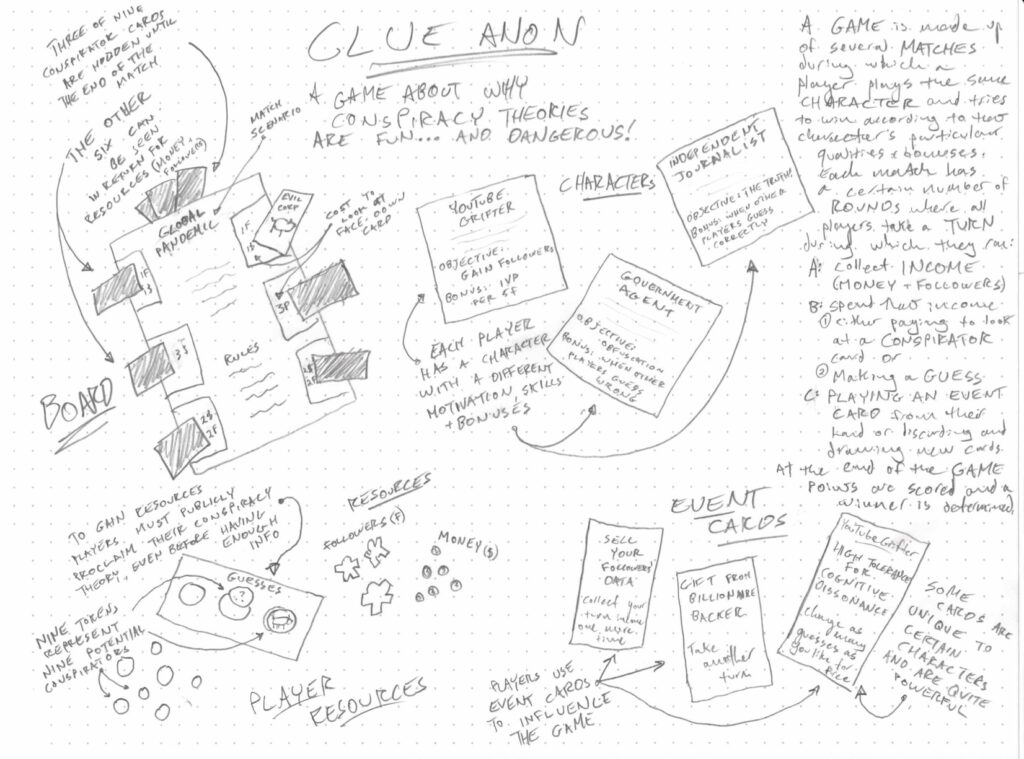

Clue-Anon: An experimental board game about why conspiracy theorizing is fun… and dangerous

Clue-Anon is an anti-authoritarian board game for up to four players.

We developed it at a time when more and more digital and tabletop games are being released that aim to teach players that conspiracism is dangerous. In contrast, our game recognizes that conspiracism is often attractive because it is playful and creative, and because it harnesses people’s skepticism and critical thinking, albeit towards nefarious ends.

The game is inspired by the rise of the Q-Anon conspiracy fantasy, which repackages heinous anti-Semitic myths to suggest a vast global conspiracy to abduct and torture children. In particular, Clue-Anon reflects on the game-like nature of this fantasy, where believers/players use digital media to create conspiracist communities that manifest in the offline world, sometimes violently.

The game asks players to take on the role of media manipulators, who each have something to gain from spreading the conspiracy: the social media corporations is eager to make money; the megalomaniacal YouTube grifter wants followers; the troll armies is just in It for the laughs; true believers want to grow their cult; only the independent journalist seems to want to learn the truth.

By imagining themselves in these roles and strategizing accordingly, players learn that conspiracies can be fun, but are also the product of intentional manipulation.

Scenario

The following scenario is a fictional composite of real playtesting experiences. Due to the sensitive nature of the topic, we do not record playtest sessions of player responses but, rather, rely on fieldnotes and participant-observation.

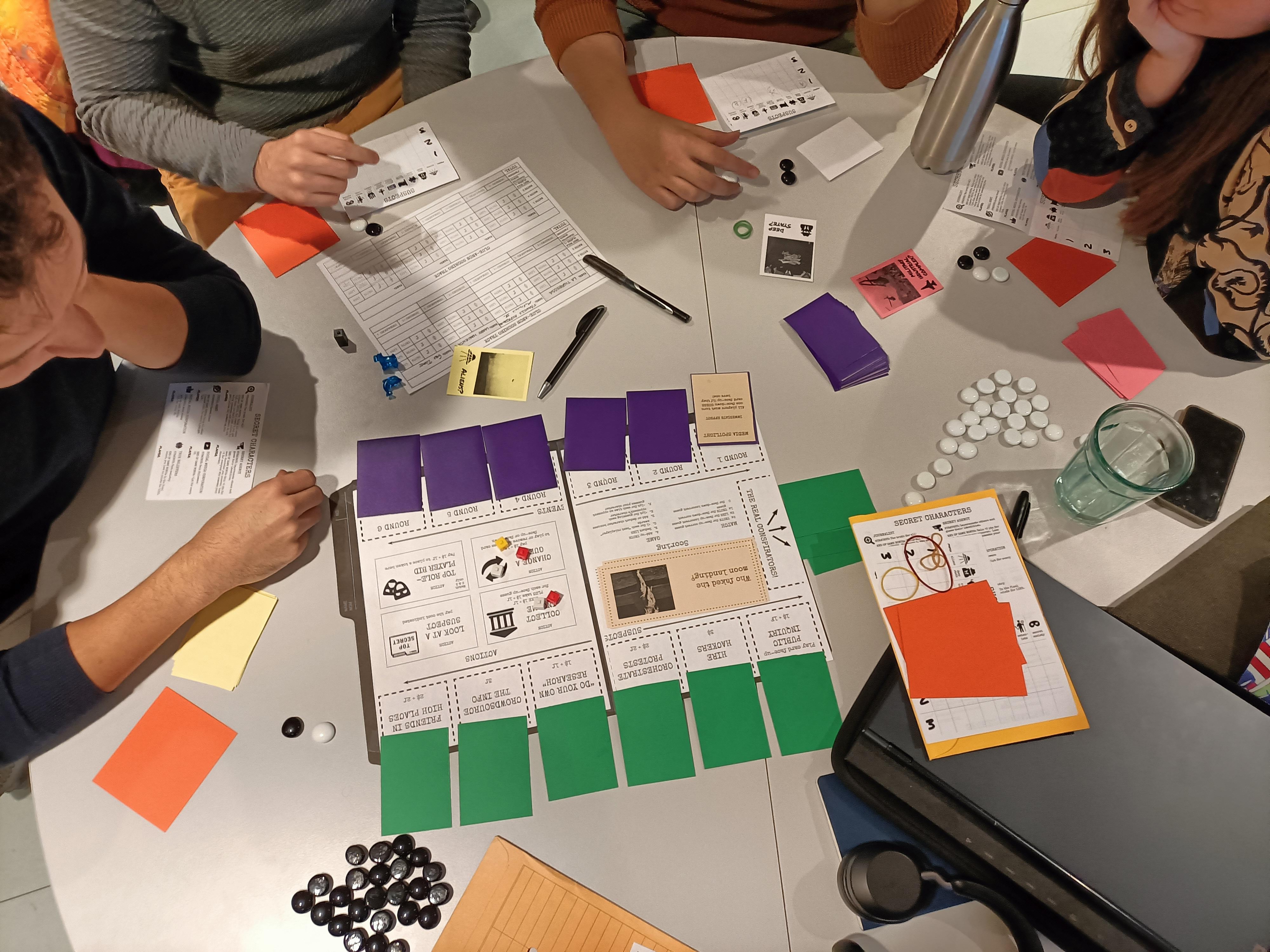

Sam, Des, Vish and Moos sit down to play Clue-Anon.

They are met with an enigmatic board. In each match, the players must try to discover which three parties are engaged in a nefarious conspiracy, this case, say “who unleashed the global pandemic?”

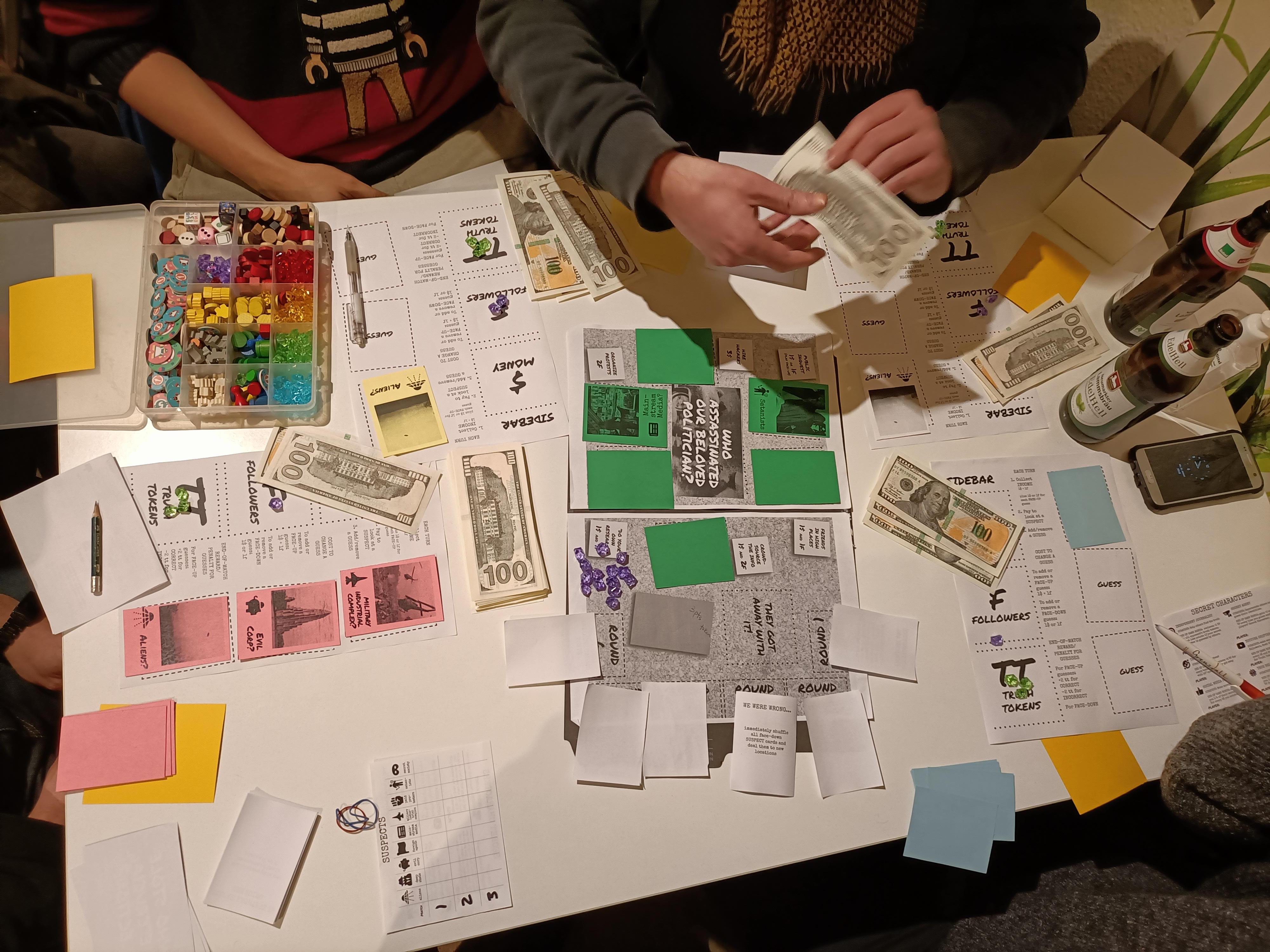

In each match, the same nine cards, representing nine conspirators (including the Military Industrial Complex, Aliens, Satantists, the Deep State) are dealt: three “real conspirators” are hidden underneath the board; the six remaining are placed face-down on spaces on top of the board. The players won’t know until the end of the match (after six turns) who the three “real conspirators” are. How will they find out?

On the surface, the objective of the game is fairly simple: players must take turns spending in-game resources (money and followers) to look at these six face-down suspect cards on top of the board, in order to deduce the remaining three “real conspirators” beneath the board. But things are a little more complex!

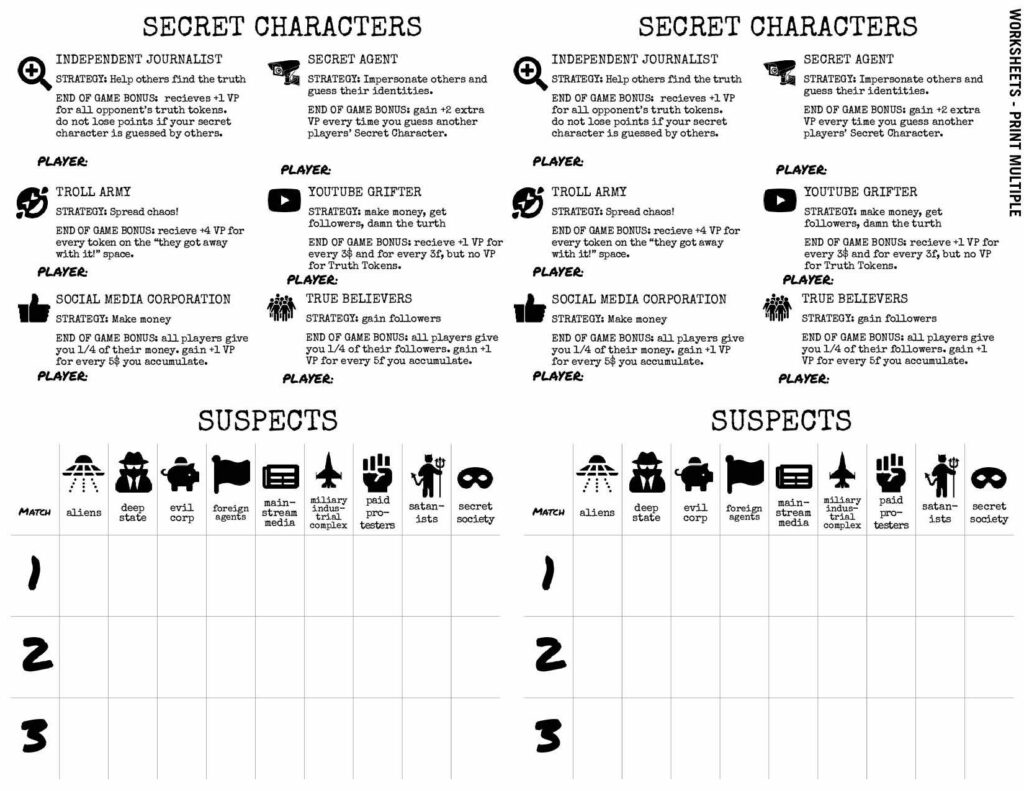

Players start the game by drawing character cards, which they keep secret. These characters have special objectives beyond just guessing the conspiracy correctly. Sam draws the Independent Journalist character: she will get a bonus if the other players guesses the true conspirators. By contrast, Des drew the True Believers character: their goal is to accumulate as many followers as possible. Meanwhile, Vish draws the Social Media Corporation character: he’ll be trying to make as much money as he can. And Moos is playing the Intelligence Agent, whose trying to guess everyone else’s secret character. But all of them will be pretending to be an Independent Journalist: everyone wants their opponents to believe that all they care about is the truth. They’ll only reveal their characters at the end of the game. If other players guess their identity, they’ll lose points.

As the game begins, each player gets resource tokens representing one dollar and one follower, and they’ll get this amount again at the outset of each turn.

In the first rounds, players use their resources to take a look at the six conspirators on top of the board, noting who isn’t part of the “real” conspiracy on private pieces of paper.

Each round, an event card is revealed, changing the flow of the game and introducing more chance. For example, players can “sell their followers’ data” to make money, or gain followers from a celebrity endorsement.

The event cards represent things that might happen in the story of a conspiracy theory’s rise to prominence.

It soon becomes clear to all the players that they simply don’t have enough resources (money and followers) to look at all six face-down conspirator cards in the six rounds of the match. How to get more resources? They must lie.

In the second round, even before it’s possible to know who the three hidden “real conspirators” are, Vish places a token face up in front of him, announcing he believes the Evil Corporation is one of the three conspirators. Is he lying? Is he guessing? At the end of the match, if Vish is right in his guess, he’ll earn points; if he’s wrong, he’ll lose them. But maybe he’ll change his guess before the end of the match. Or maybe he’s the True Believers character, and his special power is that he doesn’t lose points for wrong guesses… The other players are left to wonder: should they follow suit and also guess that the Evil Corporation is in on the conspiracy? In any case, every turn from now until the end of the match, Vish is going to get extra money and followers as a reward for propounding his public guess, and he’ll use them to look at more conspirator cards.

Soon almost all the players have made public guesses and are raking in the resources, but not Sam. Does that mean she’s the Independent Journalist? Or maybe she’s just bluffing… Meanwhile, Des has placed three public guesses and seems really confident… What’s their game? Moos decides to bet on Des: with that kind of confidence, Des must be the Journalist. But then, when Des makes a guess that Moos knows is wrong, their confidence is shaken. Meanwhile, Vish has accumulated tons of money and only late in the match do his opponents realize that he must be the Social Media Corporation. Had they known earlier, they might have taken steps to undermine his strategy…

The match ends and the three “true” conspirators are revealed. Each player is awarded points for their correct guesses and penalized for their incorrect guesses. Perhaps they play another match and add their points to their tally. After 2 or 3 matches, the game ends and the players finally reveal their secret characters and gain (or lose) extra points, depending on bonuses: Sam, the Independent Journalist, gets extra points for every time the other players correctly guessed the real conspiracy… Vish, the Social Media Corporation, gets extra points for his huge stash of money…

What do players think?

After the match, the four friends talk it over.

Sam enjoyed playing the Independent Journalist and reflects on how hard it was to convince other players she was genuine, when Des and Moos were also falsely claiming to be the Journalist.

Des was initially frustrated because they realized they would never be able to get enough resources or have enough time in a match to look at all six face-down suspects, and so deduce the three “true” conspirators: they tend to like games where the path to victory is clear. But after a round or two they got into the hoaxing and really sunk into their Government Agent character. It reminded them of stories they’d heard from their grandmother about growing up in an authoritarian state, where the government purposely spun conspiracy theories in order to defame opponents and distract people from their own nefarious activities.

Vish reflects that the character of the YouTube Grifter was the most important, because it revealed how monetized social media platforms encourage conspiracism that starts as entertainment but quickly descends into paranoia… or worse.

Sam thinks the game is useful because it teaches people to be sceptical and think critically about who is propounding conspiratorial narratives and why. But Moos reflects that the game teaches a dangerous lesson: that all conspiracy theories are equally baseless and that anyone who propounds them is crazy or manipulative. What about the conspiracies that we know are true, such as those that go on all the time in capitalism where powerful people meet in secret to maintain and extend their power? The game might reinforce a kind of liberal cynical distance that presumes that the official narrative, propounded by the media and politicians, is genuine and that all conspiracy theorizing is pathological.

Could they play it with their families or friends who are in the grips of conspiracy fantasy?

The question evokes nervous laughter. Yeah, says Des. My brother spent all his time during the lockdown rabbit-holing into weird conspiracy theories on YouTube… but he got there through his love of games, so maybe this would be a way to start a conversation.

Moos feels his family, who are refugees, would find it too confusing: they’d definitely get the concepts, but the rules are a bit too complex and clunky.

Sam is going to bring the game to her next board games nights with her friends, who work together in a feminist collective. She wonders if the game could be adapted to help them think about how to combat the anti-feminist and anti-trans conspiracy theories they encounter.

Vish wants to see if he can play it with teenagers in the community centre where he volunteers, who often come to him with wacky conspiracy fantasies which they mostly think of as jokes, but that sometimes lead to obsessions.

Clue-Anon is currently under development and will be released as a print-at-home game under Creative Commons licensing later in 2023. For updates, please subscribe to the designer, Max Haiven’s newsletter.